Theories of motivation emphasize the positive role that perceived competence in physical activity can intrinsically motivate a person to continue that activity. Research shows that mastering a goal is most strongly related to positive outcomes, such as increased self‐perception, autonomous motivation, enjoyment, and behavioral persistence.8 A successful strategy, used by healthcare professionals to educate men and women on their proficiency with PFM exercises, is the use of biofeedback as part of a training device.9 Delgado et al.,10 noted that the use of a PFM training device appeared to help women gain confidence that they were doing the exercises properly and motivated them to continue.

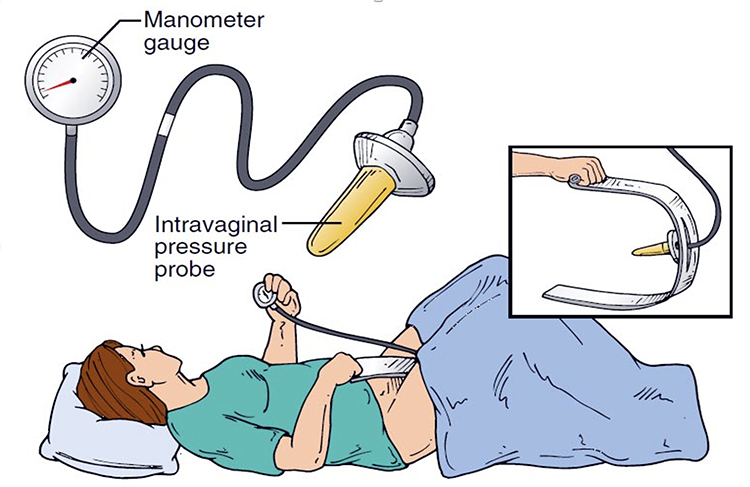

In the 1950s, when Southern California obstetrician and gynecologist Arnold Kegel described exercises (called “Kegels”) to strengthen the PFMs in women with stress UI, he designed a biofeedback device with an intravaginal pressure probe for use at home. When Kegels are performed correctly and regularly, women, across all age groups, can experience up to 70% improvement in the symptoms of stress UI. However, women report a lack of confidence in performing the exercise correctly, the time commitment needed, and inadequate instruction as factors in adhering to a pelvic training program.

Technological advancements have resulted in the availability of numerous home-based PFM training devices and smartphone mobile applications for women.11-13 These devices and applications can aid women in performing PFM exercises and some provide feedback on muscle contractions and the number of exercises performed.

There are several intravaginal devices available for in-home use that allow women to have real-time verification that they are performing PFM exercises correctly and consistently by guiding them through the PFM elevation using visual feedback. The PeriCoach and Axena Health’s leva® have been tested in women with stress UI.

Barnes and colleagues14 randomized 54 women to a silicone-coated vaginal perineometer called PeriCoach or supervised PFM physical therapy (PFPT). The PeriCoach was coupled with a mobile app that prompted 2 sets of exercises per day, while the PFM physical therapy consisted of 4, in-person therapy sessions. After 3 months of intervention, home BF had a mean decrease in LUTS symptoms and was found to be noninferior to supervised PFM physical therapy.

The Leva®, a vaginal insert device, has a Bluetooth-linked smartphone-driven app demonstrating movements detected by accelerometers (not pressure) contained within the device.15 It can detect a “correct” upward and inward PFM contraction from an incorrect Valsalva, which results in downward deflection of the device. The app can also be programmed to deliver reminder cues to complete exercises. Besides the visual feedback from the app, leva® device users have the benefit of several scheduled phone call (and/or texting) visits with a trained “coach” who provides encouragement, advice, and feedback about progress. An RCT16 compared PFMT augmented with the leva® vs. PFMT alone in 77 women with SUI or stress-predominant MUI. Seventy-seven women were randomized with analysis from 61 participants, 29 with leva® and 32 controls. There was a greater reduction in stress UI episodes per day on a 3-day diary in the leva® group. A more recent study17 of the leva® was a “virtual” remote RCT of 363 women with predominant stress UI symptoms. UI episodes significantly decreased on a 3-day diary in the leva® arm.

A woman’s knowledge and willingness to pursue consistent PFM home‐training remain obstacles to successful first‐line treatment in managing LUTS. With one in four adult women suffering from urinary incontinence, a PFM device that assists, educates, and progressively adapts, could make an impactful difference, and improve the quality of life for women.

Written by: Diane K. Newman, DNP FAAN BCB-PMD, Adjunct Professor of Surgery, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

References:

- Dumoulin C, Booth J, Cacciani, L, et al: Adult conservative management. In Cardozo L, Rovner, E., Wagg A, Wein A., Abrams, P. (eds.) Incontinence, 7th International Consultation on Incontinence, International Continence Society, Bristol, UK, 2023, 795-1038.

- Carlson K, Andrews M, Bascom A, et al. 2024 Canadian Urological Association guideline: Female stress urinary incontinence. Can Urol Assoc J. 2024;18(4):83-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.5489/ cuaj.8751

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the Post‐Partum Period. ACOG Committee Opinion: Number 650, December 2015. www.acog.org.

- Quaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, Starkey M, Denberg TD, Shekelle P. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians, Nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence in women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 161(6): 429‐40.

- Dumoulin C, Booth J, Cacciani, L, et al: Adult conservative management. In Cardozo L, Rovner, E., Wagg A, Wein A., Abrams, P. (eds.) Incontinence, 7th International Consultation on Incontinence, International Continence Society, Bristol, UK, 2023, 795-1038

- Cameron AP, Chung DE, Dielubanza EJ, Enemchukwu E, Ginsberg DA, Helfand BT, Linder BJ, Reynolds WS, Rovner ES, Souter L, Suskind AM, Takacs E, Welk B, Smith AL. The AUA/SUFU Guideline on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Idiopathic Overactive Bladder. J Urol. 2024 Jul;212(1):11-20. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000003985

- Siegel A. The Kegel Renaissance. J Urol Res. 2016; 3(4):1061.

- Keshtidar M, Behzadnia B. Prediction of intention to continue sport in athlete students: A self‐determination theory approach. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2), e0171673. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171673.

- Newman DK. Pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation using biofeedback. Urologic Nursing. 2014; 34(4): 193‐202.

- Delgado D, White P, Trochez R, Drake MJ. A pilot randomized controlled trial of the pelvic toner device in female stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2013; 24(10):1739. doi:10. 1007/s00192‐013‐2107.

- Starr JA, Drobnis EZ, Cornelius C: Pelvic floor biofeedback via a smart phone app for treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Urol Nurs. 2016 Mar-Apr;36(2):88-91, 97

- Asklund I, Nystrom E, Sjostrom M, et al: Mobile app for treatment of stress urinary incontinence: A randomized controlled trial, Neurourol Urodyn 36(5):1369-1376, 2017.

- Araujo CC, Marques AA, Juliato CRT. The adherence of home pelvic floor muscles training using a mobile device application for women with urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26(11):697-703. doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000670

- Barnes KL, Cichowski S, Komesu YM, et al: Home Biofeedback Versus Physical Therapy for Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Randomized Trial, Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 27(10):587-594, 2021.

- Rosenblatt P, McKinney J, Rosenberg RA, et al: Evaluation of an accelerometer-based digital health system for the treatment of female urinary incontinence: A pilot study, Neurourol Urodyn 38(7):1944-1952, 2019.

- Weinstein MM, Collins S, Quiroz L, et al: Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial of Pelvic Floor Muscle Training with a Motion-based Digital Therapeutic Device versus Pelvic Floor Muscle Training Alone for Treatment of Stress-predominant Urinary Incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg, 2022 Jan 1;28(1):1-6.

- Weinstein MM, Dunivan GC, Guaderrama NM, et al: Digital Therapeutic Device for Urinary Incontinence: A Longitudinal Analysis at 6 and 12 Months, Obstet Gynecol 141(1):199-206, 2023.