However, as is usually the case, there has been an ongoing effort to establish the efficacy of ENZA in the same disease space. As they have both had similar outcomes when utilized in later disease states, it is not unreasonable to expect similar outcomes when utilized in this particular patient population. To that effect, Dr. Andrew Armstrong presents the results of the ARCHES trial - a multinational, double-blind, phase 3 study (NCT02677896).

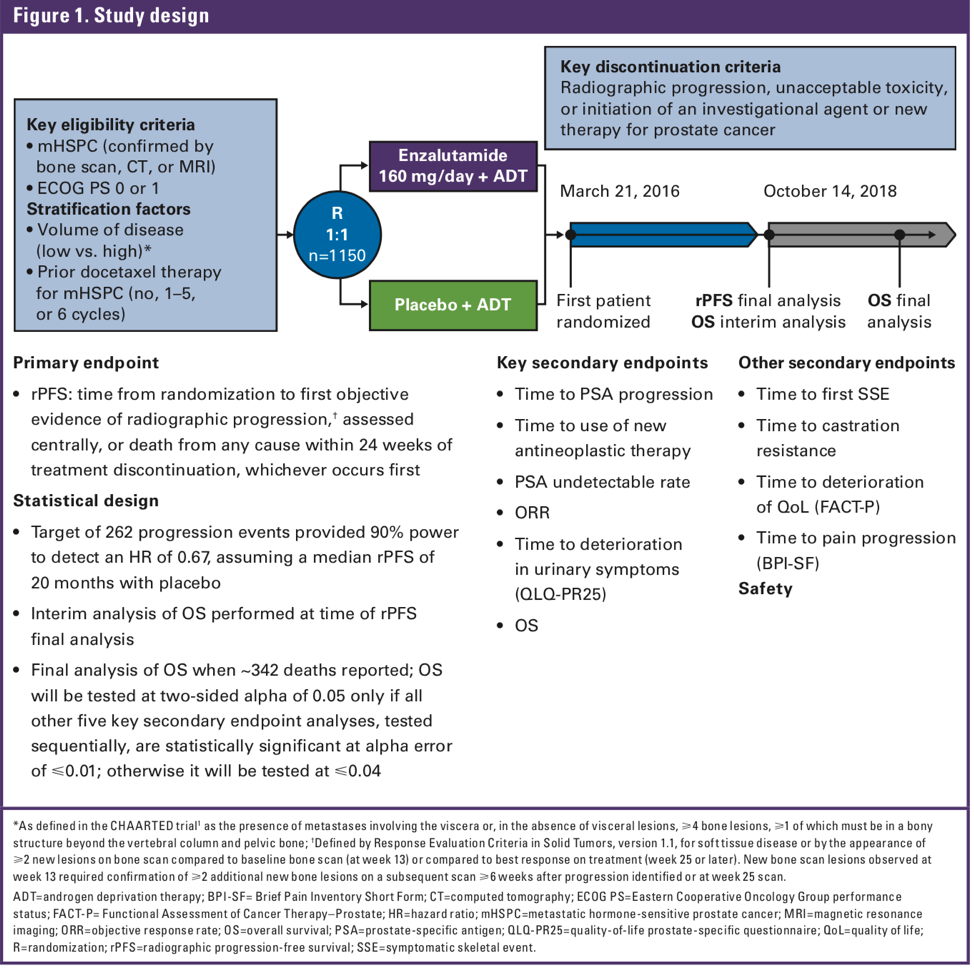

Men with metastatic hormone-sensitive PCa (mHSPC) were randomized 1:1 to ENZA (160 mg/day) + ADT or placebo (PBO) + ADT. As there has been discussion regarding the volume of disease and appropriateness of therapy, patients were stratified by disease volume (based on CHAARTED3 criteria) and prior docetaxel therapy. Full protocol listed below:

The primary endpoint was radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) assessed centrally or death within 24 weeks of treatment discontinuation. Secondary endpoints included time to prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression, PSA and radiographic responses and overall survival (OS). At the first analysis, final rPFS data will be presented and interim OS data. At the second analysis, final OS data will be presented (expected ~342 deaths). Treatment continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

In this study, 1150 men were randomized to ENZA (n=574) or PBO (n=576) in an intention-to-treat analysis. Baseline characteristics were balanced between groups and can be found below:

Of note, as 2 patients in each arm never received the drug, they were excluded from the safety profile analysis -ENZA (n=572) or PBO (n=574).

Overall, 67% had distant metastasis at initial diagnosis, 63% (727 men) had high volume disease, and 18% had prior docetaxel. He made a point to highlight this, as unlike the other studies in this space, prior docetaxel was allowed as part of the inclusion criteria–and patients were stratified based on prior docetaxel use.

Data cutoff was in October 2018, at which time 769 men were still on treatment – 76% of ENZA patients, 57.6% of placebo patients.

Median follow-up was 14.4 mo. When looking at the primary endpoint, ENZA + ADT significantly improved rPFS (NR vs. 19.4 mo, HR 0.39) and similar significant improvements in rPFS were reported in prespecified subgroups of disease volume, the pattern of spread, region and prior docetaxel (HRs 0.24–0.53).

Below is the Kaplan-Meier (KM) curve for the primary endpoint for the entire cohort, stratified by docetaxel receipt:

For all subgroups (except for patients with soft-tissue only metastases), the ENZA treated patients did better, as seen below:

Even in the soft-tissue only group, the results favored enzalutamide. Of note, he specifically highlights the fact that regardless of the volume of disease OR prior docetaxel chemotherapy, ENZA was associated with a significantly improved rPFS (HR 0.24 for low-volume and HR 0.44 for high-volume; HR 0.36 for no prior docetaxel therapy and HR 0.53 for prior docetaxel therapy).

Secondary endpoints also improved with ENZA + ADT and the full results can be found in the table below.

Unfortunately, OS data are immature and not final yet. Final results will be presented once this data is mature. At this time, only 84 deaths have been reported (25% of the required number of events). A statistically non-significant 19% reduction in deaths was observed favoring enzalutamide (HR 0.81, p =0.33).

He briefly also reviewed the quality of life data (QoL). Patients in both arms reported high baseline QoL, which was maintained over the course of the study. In a pre-specified analysis, however, time to pain progression for worst pain, as measured by question 3 of the BPI-SF score, was delayed with enzalutamide therapy (HR 0.82, p = 0.03). This is seen in the results below, stratified by prior docetaxel use:

In general, similar to studies of ENZA in other disease states, it was well tolerated. Grade 3–4 adverse events (AEs) were reported in 24.3% of ENZA pts vs 25.6% of PBO pts with no unexpected AEs. AE’s leading to withdrawal were observed in 7.2% of the ENZA treated patients and 5.2% of the placebo-treated patients. There were no reports of PRES in either arm. Ischemic cardiac disease was reported in <2% in both arms

Based on this, Dr. Armstrong and colleagues conclude that ENZA + ADT significantly improved rPFS and other efficacy endpoints compared to ADT alone in men with mHSPC, with a preliminary safety analysis that appears consistent with the safety profile of ENZA in previous CRPC clinical trials. Perhaps this may be an alternative to Abiraterone +prednisone and docetaxel for men with de novo metastatic disease?

Presented by: Andrew J. Armstrong, MD, MSc, Medical Oncologist, Duke Cancer Center, Durham, North Carolina, United States

Co-Authors: Russell Zelig Szmulewitz, MD, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Daniel Peter Petrylak, MD, Yale Cancer Center, Smilow Cancer Hospital, New Haven, CT; Jeffrey M. Holzbeierlein, MD, The University of Kansas Medical Center, Westwood, KS; Arnauld Villers, MD, PhD, Department of Urology, University Hospital Centre, Lille University, Lille, France; Arun Azad, MBBS, PhD, Monash Health, Melbourne, Australia; Antonio Alcaraz,MD, PhD, Urology Department, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain; Boris Yakovlevich Alekseev, MD, Hertzen Moscow Cancer Research Institute, Moscow, Russian Federation; Taro Iguchi, MD, PhD, Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan; Neal D. Shore, MD, Carolina Urologic Research Center, Myrtle Beach, SC; Brad Rosbrook, Pfizer Inc., San Diego, CA; Benoit Baron, MD, Astellas Pharma Inc., Leiden, Netherlands; Lucy F. Chen, MD, Astellas Pharma Inc., Northbrook, IL; Arnulf Stenzl, MD, Department of Urology, University Hospital, Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany.

Written by: Thenappan Chandrasekar, MD (Clinical Instructor, Thomas Jefferson University) (twitter: @tchandra_uromd, @JEFFUrology) at the 2019 ASCO Annual Meeting #ASCO19, May 31- June 4, 2019, Chicago, IL USA

References:

- James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med 2017;377:338–51.

- Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration‐sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:352–60.

- Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone‐sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 737–46.