(UroToday.com) The 2024 American Society of Clinical Oncology Genitourinary (ASCO GU) cancers symposium held in San Francisco, CA between January 25th and 27th was host to a session addressing the incorporation of radiation therapy, theranostics, and biomarkers into the management of renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Dr. Sophia Kamran discussed the role of radiation therapy for the management of RCC primary tumors and distant metastatic sites.

Dr. Kamran noted that the ‘historical teaching’ is that radiation is not effective for RCC in either the primary or metastatic setting, with radiation primarily reserved for palliative purposes. But in contemporary practice, is RCC radioresistant? Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SBRT or SABR) delivers a higher dose per fraction that can yield cytotoxic effects in RCC. Data supporting the efficacy of SBRT for RCC can be extrapolated from the success of radiating intracranial RCC metastases using stereotactic radiosurgery, with impressive rates of local control compared to rates provided by conventionally fractionated radiation. Advances in image guidance and motion management have facilitated the application of SBRT for primary and metastatic RCC.

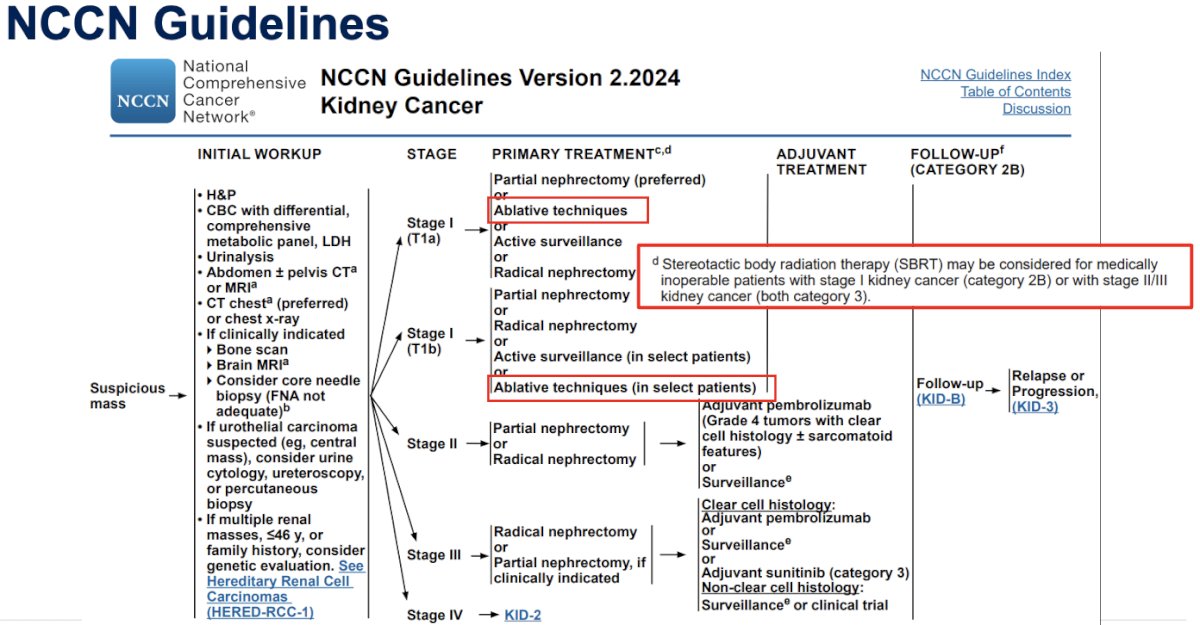

With regards to primary tumor radiation, the 2024 NCCN guidelines state that SBRT may be considered for medically inoperable patients with stage 1 kidney cancer (category 2B) or with stage II/III kidney cancer (both category 3).

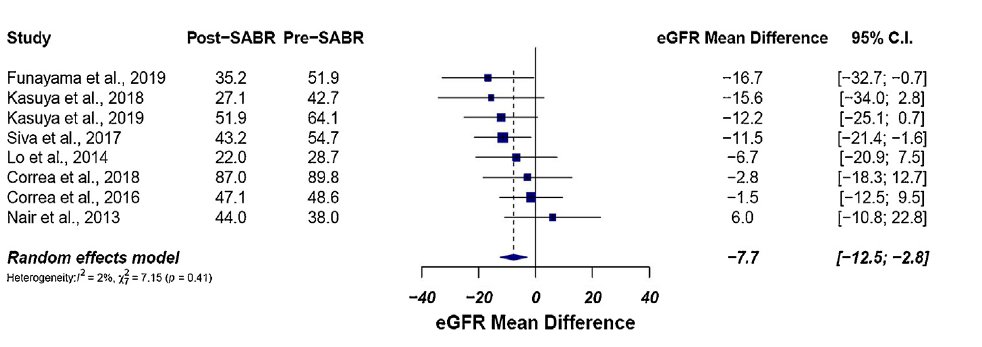

A 2019 meta-analysis of 26 studies, including 11 prospective trials, by Dr. Shankar Siva’s group demonstrated that SBRT for primary RCC achieves a local control rate of 97.2%, with grade 3-4 toxicity in 1.5% of patients.1

Notably, the average eGFR loss from baseline was only -7.7 mL/min.

More recent data has emerged from the IROCK (the International Radiosurgery Consortium of the Kidney) individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis with Siva et al. reporting the 5-year outcomes after SBRT for primary RCC in 2022. This meta-analysis included 190 patients with primary RCC across 12 institutions. Patients received either single or multiple fraction SBRT at a dose per fraction >5 Gy. The median tumor diameter was 4 cm, and 75% of patients were deemed inoperable by the referring urologist. The 5-year local failure rate was 5.5%, with single fraction SBRT yielding fewer failures compared to multi-fraction SBRT (p=0.02). There were no grade 3 or 5 toxicities, but one patient developed a grade 4 duodenal ulcer and late grade 4 gastritis. Seven (3.7%) patients required dialysis post-SBRT.2

At ASTRO 2023, Dr. Siva presented the results of the TROG 15.03 FASTRACK II trial. The goal of this trial was to investigate the efficacy of SBRT in the first multicenter phase II trial of non-surgical therapy for primary RCC. This trial included patients with:

- Biopsy-confirmed primary RCC, single lesion within a kidney

- Medically inoperable or high-risk for surgery

- Multidisciplinary decision made that active treatment warranted

- Tumor <10 cm and not abutting bowel

The primary study outcome was to evaluate local control after SBRT, assuming a 1-year local control rate of 90%. A local control rate of ≤80% would be considered not worthy of pursuing a subsequent randomized controlled trial. In this trial, the local control rate was 100%, with a 99% freedom from distant failure. The cancer specific-survival was 100%, and the mean kidney function loss was -14.6 mL/min. When these results are compared to those of radical/partial nephrectomy for analogous tumors, Dr. Kamran argued that these excellent efficacy and safety results for SBRT for primary RCC in patients who are inoperable establishedsSBRT as a new standard of care for patients not eligible for surgery. The next step is to evaluate this approach in patients who are operable (i.e., a trial of surgery versus SBRT).

What about renal tumors in the solitary kidney? A 2019 pooled data analysis of 81 patients with solitary kidneys treated with SBRT at 9 IROCK institutions demonstrated that the mean eGFR decrease was -5.8mL/min (-9% from baseline) with no patients requiring dialysis at a median follow-up of 2.6 years. More recent data presented at ASTRO 2023 of 190 patients (56 with solitary kidneys) who underwent SBRT found no significant differences in eGFR decline at all timepoints assessed (p>0.05) and no difference in ESRD or dialysis between the two groups. Multivariable analysis found that increasing tumor size and baseline eGFR was more likely associated with eGFR decline post-SBRT, with no significant association between solitary versus bilateral kidneys.

Response assessment to SBRT for primary RCC remains controversial. At present, local control is determined using CT imaging/size-based RECIST criteria, but this has limitations as an assessment tool. There are concerns for “psuedoprogression” after SBRT, whereby there is an initial size increase that may be misinterpreted as disease progression. In contrast to SBRT, ablation techniques cause immediate changes in contrast enhancement patterns. Contrast enhancement changes evolve much more slowly over time after SBRT. We can also sometimes see increase in contrast enhancement as well, due to inflammation among other reasons.

Current challenges with SBRT to primary RCC include:

- Motion management

- Insertion of fiducials as surrogates for tumor position is complicated by risk of hemorrhage in highly vascular tumors

- Potential role for MRI-based SABR to improve tumor visualization/tracking

- Tumors that have broad contact with the bowel

- Adaptive radiation may improve conformality of treatment, avoiding high dose in organs at risk

- Response assessment

What about radiotherapy for RCC oligometastases? What is known to date is that:

- SBRT can delay switch of an otherwise successful systemic therapy

- SBRT can delay systemic therapy

- SBRT can be safely used in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors

In 2021, Cheung et al. published the results of a phase II prospective multicenter study that evaluated the use of SBRT in oligoprogressive, metastatic RCC patients, who had previous stability or response after ≥3 months of tyrosine kinas inhibitor (TKI) therapy and who developed progression of five or fewer metastases. The SBRT doses ranged based on the anatomical site irradiated. The 1-year local control of irradiated lesions was 93%. The cumulative incidence of changing systemic therapy was 47% at 1 year, with a median time to change in systemic therapy of 12.6 months.3

A similar trial by Hannan et al. published in 2021 demonstrated that SBRT can delay switch to next-line drug therapy, irrespective of whether patients were on a TKI, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), or combination therapy. In this trial, 20 patients were enrolled who were on TKIs (n=8), ICI (n=8), or combination therapy (n=4) with previous stability on treatment but subsequently with evidence of 1-3 metastatic site disease progression. The 1-year local control of irradiated lesions was 100%. The median time to change in systemic therapy was 11.1 months (95% CI: 4.5 to 19.3 months).4

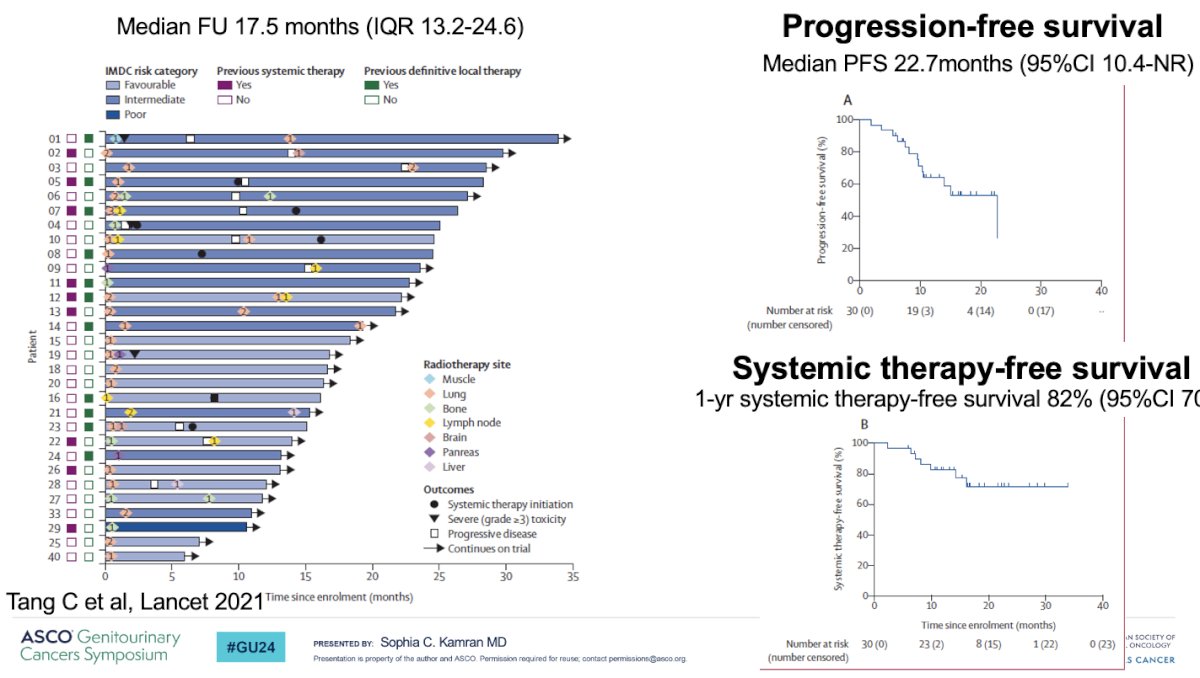

In a 2021 Lancet Oncology publication, Tang et al demonstrated that sequential SBRT can defer systemic therapy. In their single arm feasibility phase 2 trial, 30 RCC patients with ≤5 lesions were enrolled. Patients must have not received prior systemic therapy or only one prior if stopped one month prior to treatment. Patients received SBRT in ≤5 fractions with ≥7 Gy/fraction to all lesions, if safe based on anatomical location, otherwise hypofractionation was delivered. The co-primary endpoints of this trial included feasibility and progression-free survival. Patients were maintained off systemic therapy until evidence of disease progression. The median progression-free survival was 22.7 months, and the 1-year systemic therapy-free survival was 82%. Notable limitations to this trial were the inclusion of a highly-selected population, the decision to pursue systemic therapy at physician and patient discretion, and the short follow-up time of 17.5 months.5

Dr. Kamran noted that data appear to indicate that SBRT can be an effective treatment for highly selected patients with metastatic RCC. We may be able to improve upon outcomes due to the immunostimulatory effects combining SBRT + ICI to enhance therapeutic response. The phase II NIVES study of nivolumab in combination with SBRT in pre-treated patients with metastatic RCC included 69 patients who received 10 Gy x 3 fractions to a single lesion, seven days after the 1st infusion of nivolumab. The study hypothesis was that the addition of SBRT would improve the objective response rate (ORR) from 25% with nivolumab alone to 40% with nivolumab + SBRT. In this trial, mostly lung and lymph node metastases were irradiated. At a median follow-up of 26 months, the ORR was 17% and the disease control rate was 55%. The median PFS was 5.6 months (IQR: 2.9 – 7.2),6 which compares favorably to the 4.6 months observed with nivolumab in the CheckMate-25 trial. The median OS was 20 months. Grade 3-4 toxicity was observed in 26% of patients (for comparison, 19% in CheckMate-25). Dr. Kamran highlighted that this trial demonstrates the safety of combination SBRT + ICIs, with a higher ORR for irradiated versus non-irradiated lesions (29% versus 12%). Important limitations included the small sample size, lack of central radiographic review, lack of process to determine which lesions to irradiate, and inclusion of non-clear cell histology, which tends to be less responsive to ICIs.

Are two ICIs combined with SBRT better than one? The Phase II RADVAX-RCC trial included 25 patients who received nivolumab/ipilimumab + SBRT (10 Gy x 5 to 1-2 lesions). The ORR was 56%, and the median PFS was 8.2 months, which was equivalent to that observed in CheckMate-214.7 The grade 3-4 toxicity was 36% (46% in CheckMate-214).

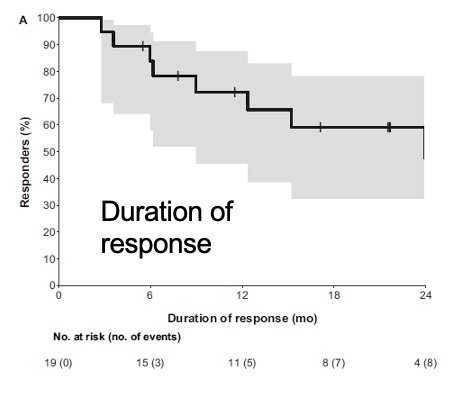

In contrast to these trials, the RAPPORT trial, which included 30 patients with oligometastatic clear cell RCC with 1 – 5 lesions, treated all sites of disease with SBRT (20 Gy x 1) followed by pembrolizumab for 8 cycles.8 Notably 4/30 patients discontinued pembrolizumab due to pneumonitis, and 2/30 discontinued due to disease progression. In total, 83 lesions were irradiated, of which 77% received SBRT (remainder received conventional radiotherapy). There were no grade 4 or 5 adverse events. At a median follow-up of 28 months, the median duration of response was 24 months, and the 1- and 2-years freedom from local progression were 94% and 92%, respectively.

The 1- and 2-year progression-free survivals were 60% and 45%, respectively. The 1-year cumulative incidence of 1st failure was distant in 30% of cases and local in 7%. The patterns of progression in the 17 patients who progressed were as follows:

- Progression at a previously irradiated local site: 3 patients

- Distant progression: 12 patients

- Synchronous local and distant progression: 2 patients

In summary, the RAPPORT trial demonstrated that:

- SBRT+ pembrolizumab is a reasonable treatment option for oligometastatic RCC

- Well-tolerated, high local control rates

- The 2-year PFS of 45% compares favorably with the 2-year PFS from KEYNOTE-427 study (pembrolizumab monotherapy) which was 22.3%

- Limitations include small sample size, single-arm design, and inclusion of a highly selected population

- Encouraging outcomes observed with total metastatic ablation and pembrolizumab in oligometastatic RCC warrant further investigation

- What remains unclear is if the higher ORR and improved PFS is due to treatment of all oligometastatic lesions or due to the sequencing of immunotherapy after SBRT

Future ‘frontiers’ in this space include:

- Targeting immunologically ‘cold’ lesions in metastatic RCC undergoing ICI therapy

- Additional research efforts into the sequencing, timing, number of sites, radiotherapy field, dose, and biology of ICI + SBRT

- Further trials to evaluate combination SBRT + targeted systemic therapy (sunitinib, pazopanib, sorafenib) + ICI

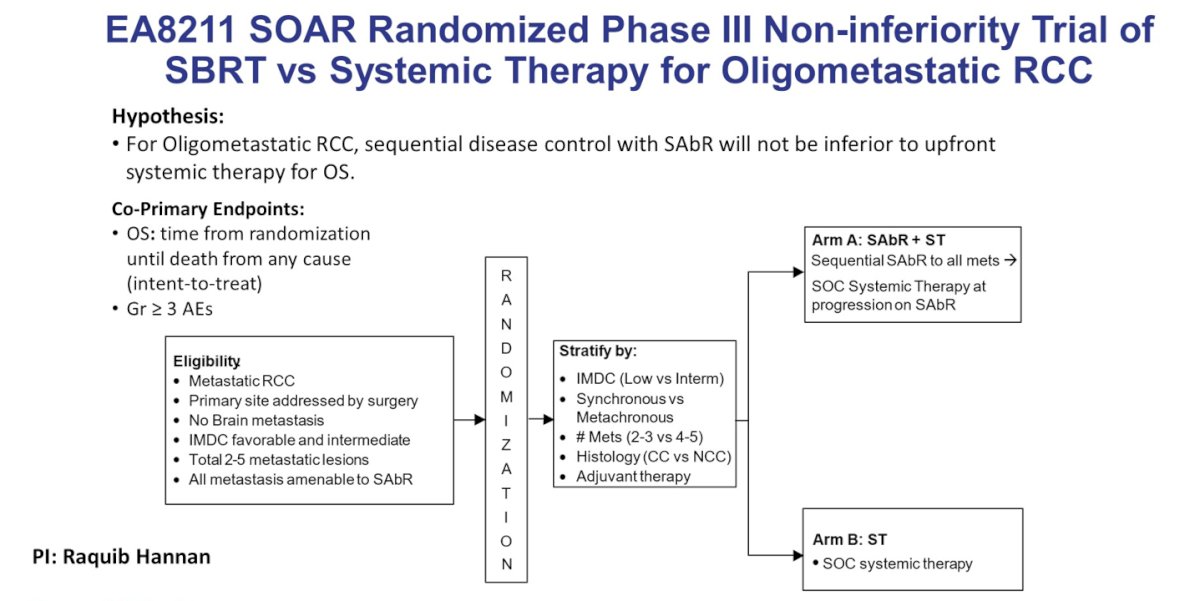

The EA8211 SOAR randomized phase III non-inferiority trial will compare sequential SBRT to all metastases with subsequent standard of care systemic therapy at progression on SBRT to standard of care systemic therapy in patients with oligometastatic RCC:

What about treating the primary lesion with SBRT in metastatic RCC? Randomized studies in the cytokine era showed that initial nephrectomy for select patients with metastatic RCC was associated with prolonged survival. Yet, CARMENA has changed the standard of care:9

- In the era of targeted therapy, cytoreductive nephrectomy benefits fewer patients who present with metastatic RCC at initial diagnosis compared to the era of cytokine therapy.

- Intermediate- and poor-risk patients likely should not receive cytoreductive nephrectomy

- Cytoreductive nephrectomy may still be a reasonable option for select patients:

- Oligometastatic disease

- Good performance status

- Minimally symptomatic from cancer

- Bulk of tumor burden in the primary

- There may be a role to cytoreduction of primary tumor using SBRT in metastatic RCC (similar to CARMENA, also similar to STAMPEDE in prostate cancer)

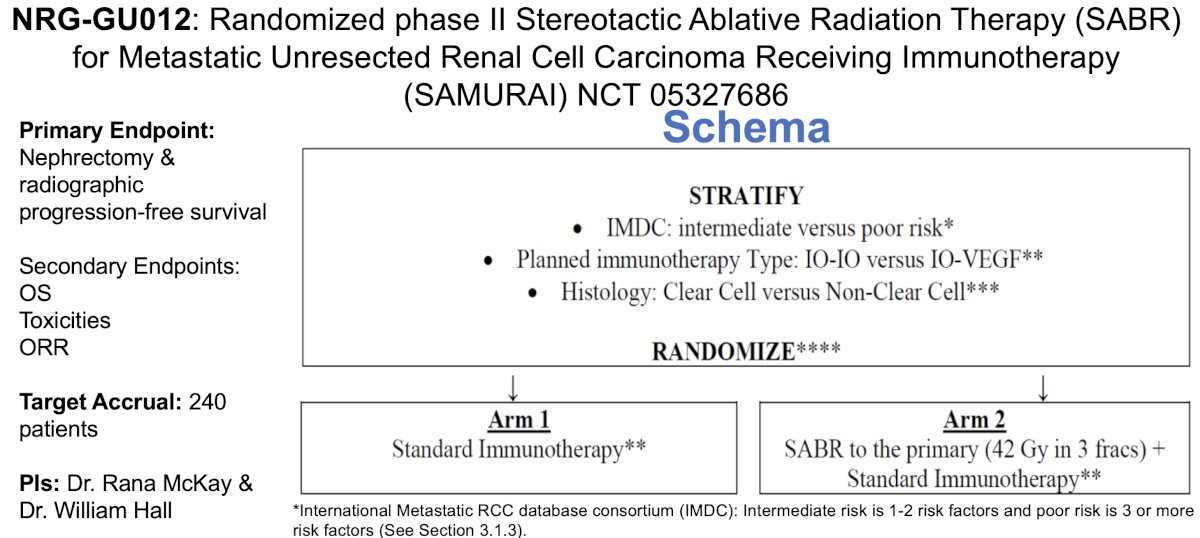

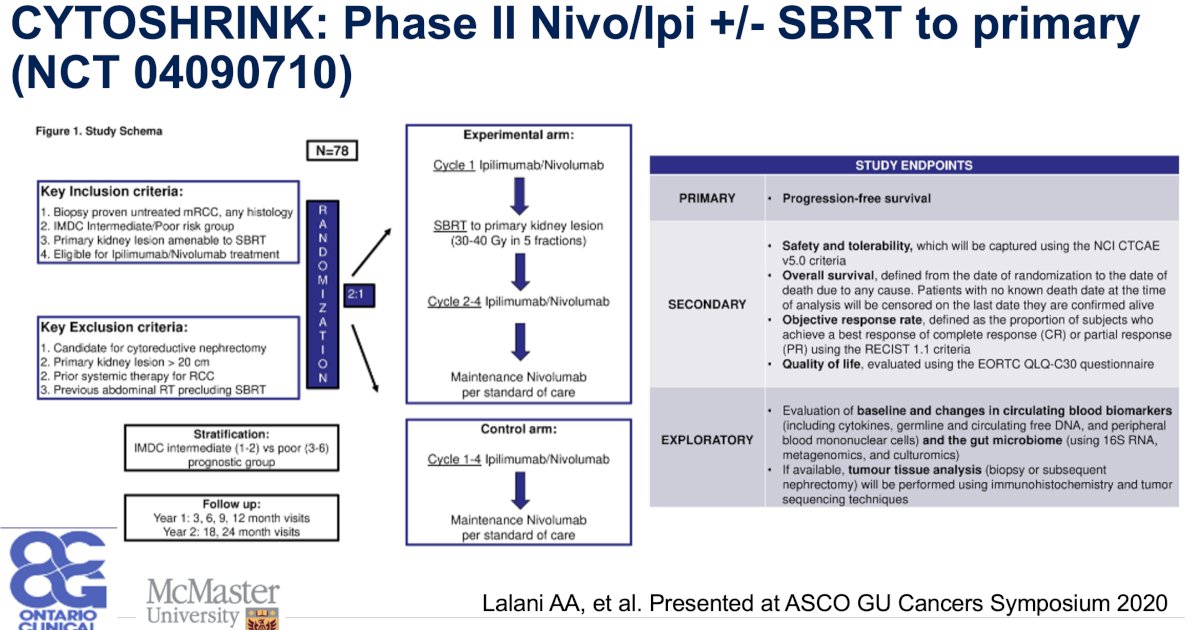

- This concept will be evaluated in the phase II SAMURAI (NCT 05327686) and CYTOSHRINK (NCT 04090710) trials

Dr. Kamran concluded that:

- Radiation is an effective treatment modality for RCC (in either the primary or metastatic setting)

- In oligometastatic disease, it can be used to extend a successful systemic therapy or delay initiation of systemic therapy

- Radiation may be combined with ICI to enhance therapeutic response and improve outcomes

- More work needs to be done to understand the remaining questions (treatment response assessment, dose, timing, sequence, treatment site [metastasis versus primary], etc.)

- No phase III randomized trial have been completed to date

- Multiple trials underway

- RCC is not radioresistant

- Radiotherapy should be considered as part of multidisciplinary care

- Accrual to ongoing trials is critical to advance the field and solidify the role of radiotherapy for our patients with RCC

Presented by: Sophia C. Kamran, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Written by: Rashid Sayyid, MD, MSc – Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Clinical Fellow at The University of Toronto, @rksayyid on Twitter during the Genitourinary (GU) American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, Thurs, Jan 25 – Sat, Jan 27, 2024.

References:1. Correa RJM, Louie AV, Zaorsky NG, et al. The Emerging Role of Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for Primary Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur Urol Focus. 2019;5(6):958-69.

2. Siva S, Ali M, Correa RJM, et al. 5-year outcomes after stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for primary renal cell carcinoma: an individual patient data meta-analysis from IROCK (the International Radiosurgery Consortium of the Kidney). Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(12):1508-16.

3. Cheung P, Patel S, North SA, et al. Stereotactic Radiotherapy for Oligoprogression in Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer Patients Receiving Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy: A Phase 2 Prospective Multicenter Study. Eur Urol. 2021;80(6):693-700.

4. Hannan R, Christensen M, Hammers H, et al. Phase II Trial of Stereotactic Ablative Radiation for Oligoprogressive Metastatic Kidney Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;5(2):216-24.

5. Tang C, Msaouel P, Hara K, et al. Definitive radiotherapy in lieu of systemic therapy for oligometastatic renal cell carcinoma: a single-arm, single-centre, feasibility, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(12):1732-1739.

6. Masini C, Iotti C, De Giorgi U, et al. Nivolumab in Combination with Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Pretreated Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Results of the Phase II NIVES Study. Eur Urol. 2022;81(3):274-82.

7. Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;378(14):1277-1290.

8. Siva S, Bressel M, Wood ST, et al. Stereotactic Radiotherapy and Short-course Pembrolizumab for Oligometastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma-The RAPPORT Trial. Eur Urol. 2022;81(4):364-72.

9. Mejean A, Ravaud A, Thezenas S, et al. Sunitinib alone or after nephrectomy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018 Aug 2;379(5):417-427.