(UroToday.com) The 2023 ASTRO annual meeting included a session on exploring ethical and legal implications of artificial intelligence in medical practice, featuring a presentation by Dr. Tony Quang discussing legal and regulatory implications of artificial intelligence in clinical oncology. Dr. Quang notes that there has been a massive uptick in artificial intelligence manuscripts over the last several years. As follows are the results of a PubMed search of “artificial intelligence and radiation oncology”:

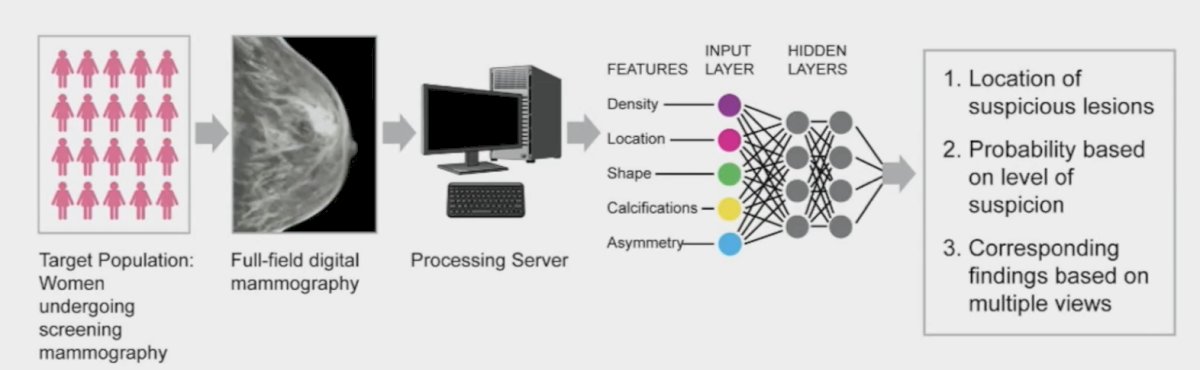

Importantly, artificial intelligence is more than just algorithms, it also includes regulations, liability, informed consent, privacy, ethics, ASTRO Resolutions, innovators/leaders, and venture capital. Dr. Quang’s favorite definition of artificial intelligence is that it uses a machine to perform tasks that typically require human thought. For example, as follows is a model of a graphic representation of mammography artificial intelligence:

Types of artificial intelligence solutions include:

- White box interpretable: linear model decision trees

- Black box explainable: merely produces output without any insights of how the output is reached, gives post-hoc explanations for algorithm output, and should be tested for safety and efficacy like in phase I clinical trials

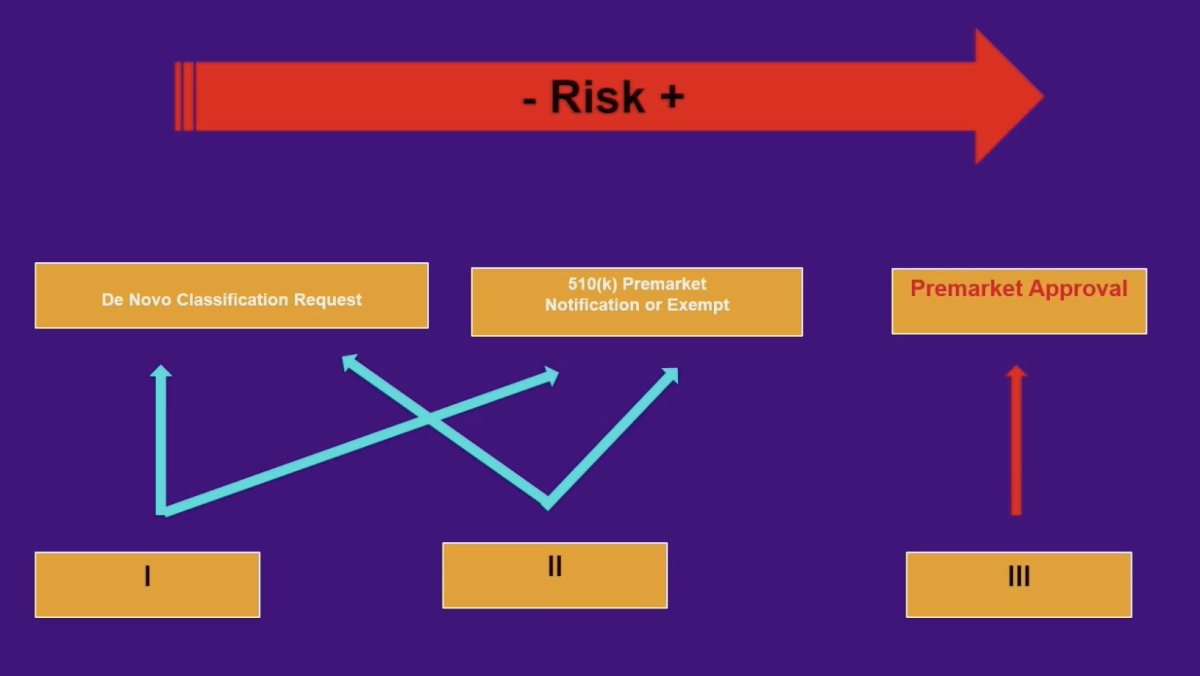

As such, there are several artificial intelligence concerns, such as (i) black box, (ii) input data, (iii) lack of specific training, and (iv) incongruent decisions—physician versus artificial intelligence. The FDA regulation of artificial intelligence follows a functional approach rather than an artificial intelligence-specific framework, which includes three pathways based on patient risk exposure. For a medical device, intended use has to be stated in the process leading to market authorization for FDA clearance/approval. Additionally, there is clinical monitoring as part of post-market surveillance. As follows is an algorithm for risk based on increasing class risk:

Recently, Congress signed into law the 21st Century Cures Act. This was signed into law on December 13, 2016, to accelerate medical product development and bring new innovations to patients faster and more efficiently. This Act authorized $500 million over nine years to help the FDA cover the cost of implementation, creating the following exemptions to the legal definition of a medical device and removing FDA oversight:

- Administrative support

- Maintenance of a healthy lifestyle

- EHR – improved interoperability and the prevention of information blocking related to the access, exchange, or use

- Storage and display of clinical data

However, the aforementioned is true, unless the device is intended to acquire, process, or analyze a medical image for the purpose of:

- Displaying, analyzing, or printing medical information

- Supporting or providing recommendations to a healthcare professional

- Enabling such health care professionals to independently review the basis for such recommendations to make a clinical diagnosis or treatment decision regarding an individual. A physician must retain the ability to “fact-check” the artificial intelligence output

The theory of negligence in malpractice encompasses duty of care, breach of duty, proximate cause, and damage. The courts defer to the medical community (professional societies, practices of peer physicians, and institutions) to evaluate standards of care. To summarize, there are several types of liability that should be highlighted:

- Medical malpractice

- Institutional liability

- Vicarious liability

- Product liability

- Enterprise liability

- Privacy (HIPAA)

Dr. Quang then provided the example of Taylor versus Intuitive Surgical (2017). The issue was whether the surgeon operating the da Vinci surgical robot or the device itself was responsible for the injury of a patient undergoing a robotic prostatectomy. da Vinci System provided a manual to the surgeon stating that the maximum recommended BMI for robotic surgery is 30, however the patient’s BMI was 39 and the surgeon decided to operate anyway. The patient was left with a poor quality of life, including respiratory issues requiring ventilator support, neuromuscular damage that left the patient unable to walk unaided, and incontinence. He passed away from complications four years after surgery. The patient argued that the manufacturer was ultimately to blame for failing to adequately train or warn the surgeon. The jury determined that the company had a duty to warn the physician regarding the nature of the robotics system and that the company did provide an adequate warning to the physician. The Washington State Supreme Court found that even though the company had trained and warned the physician, manufacturers also have a duty to warn hospitals, as purchasing agents, about the danger of their products.

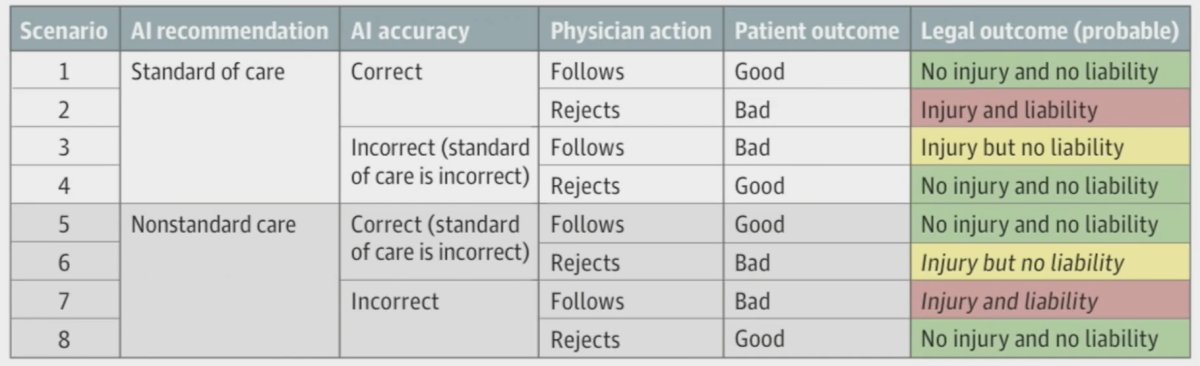

What is important to highlight is that “standard of care” is the care provided by a competent physician who has a similar level of specialization and available resources. Importantly, physician liability may result from using artificial intelligence in clinical practice, and patient harm occurs. This may manifest as artificial intelligence making a correct recommendation according to the standard of care, but the physician rejects it, and/or if the physician follows an incorrect artificial intelligence recommendation that falls outside of the standard of care. As follows are examples of potential legal outcomes related to the use of artificial intelligence in clinical practice:

Dr. Quang emphasized that the “safest” way to use medical artificial intelligence from a liability perspective is as a confirmatory tool to support the existing decision-making process, rather than as a source of ways to improve care.

Finally, Dr. Quang provided a list of actionables for positioning artificial intelligence in clinical oncology:

- Learn how to better use and interpret artificial intelligence algorithms

- Encourage professional organizations to take active steps to evaluate practice specific algorithms, and provide guidelines for implementation

- Ensure administrative efforts to develop and deploy algorithms in hospitals

- Check with a malpractice carrier

- Be part of the artificial intelligence development process

Dr. Quang concluded this presentation by discussing legal and regulatory implications of artificial intelligence in clinical oncology with the following take-home messages:

- Physicians need to play a leading role in defining the standard of care for artificial intelligence use

- Medical malpractice liability using artificial intelligence in clinical practice is unsolved with an evolving legal framework

- Following the standard of care is protective for physicians against liability -- artificial intelligence should be used more as a confirmatory tool rather than de novo in clinical decisions

- Use of interpretable artificial intelligence is preferable over black box models

- Current law disincentivizes physician use of artificial intelligence, potentially to the patient’s detriment

Presented by: Tony Quang, Veterans Affairs Long Beach, Long Beach, CA

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Urologic Oncologist, Associate Professor of Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Wellstar MCG Health, @zklaassen_md on Twitter during the 2023 American Society for Therapeutic Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) 65th Annual Meeting held in San Diego, CA between October 1st and 4th, 2023