It is well-known that renal colic caused by a renal stone could be a very painful event often treated with opioids. It is also known that prescribed opioids have been identified as the critical initial exposure for chronic opioid use and opioid abuse. Following a single exposure to opioids, there is a 6% risk for long term use, and when the initial exposure is for one week or more, there is a 14% risk of long-term use.1 Illegal opioid use is eight times higher in those with prior prescribed opioids compared to those without prior exposure2.

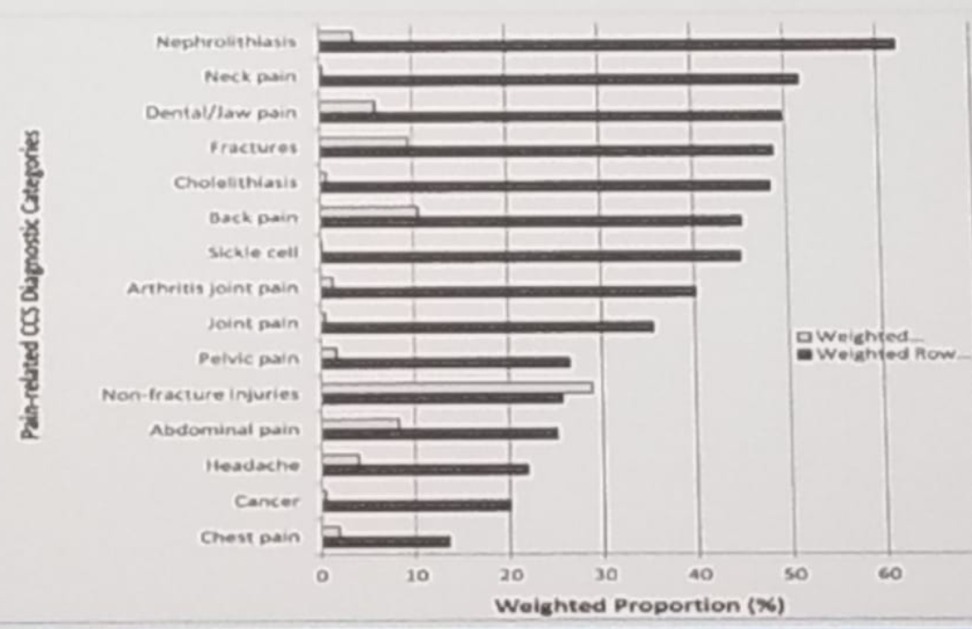

In a study assessing the use of narcotics in patients with kidney stones with over 23,000 patients, the current opioid use was greater in patients with prior history of stone disease vs. those without any history of stones (10.9% vs. 6.1%)3. It has been shown that 16.7% of all emergency department visits resulted in opioid prescription4, with nephrolithiasis being the number one reason for an opioid prescription (see Figure 1). This may be an important source of repeated opioid exposure. Opioid users were shown to be more likely to have had stones. It has also been demonstrated that stone formers fill more opioid prescriptions than non-stone formers (2.53 vs. 0.97, p<0.001) (5), and stone formers with depression or anxiety filled significantly more prescriptions than stone formers without these conditions. Other data show that 40% of stone formers receive a new opioid prescription during the episode, and 20% of these patients continue to use opioids the following year.

Published data analyzing almost 2000 veterans following surgery for stones showed that 80% of these patients received an opioid prescription with a median of 10 days of supply, and the type of surgery did not affect the prescription. The data also showed that post-traumatic stress disorder increased the odds ratio of a high daily dose of opioids6.

Non-opioid prescription medications for patients undergoing ureteroscopy for stones include the stent “cocktail’, which consist of oxybutynin, tamsulosin, phenazopyridine, and diclofenac. These have demonstrated no difference in postoperative pain requiring subsequent opioid therapy7. Other pain medications used include acetaminophen/gabapentin preoperatively, Belladonna and Opium Suppositories (B & O Suppositories) and ketorolac intraoperatively, with acetaminophen, Motrin, oxybutynin, and tamsulosin used postoperatively.

Dr. Pais concluded by stating that recognizing stone formers as a cohort to increased risk for recurrent opioid exposure is critical. Most of these patients usually receive opioid prescriptions, up to 50% have received refills, and up to 20% were still using the medication one year later. Lastly, non-opioid pathways are available with good efficacy, having successfully treated acute colic and postoperative pain.

Figure 1 – Reasons for opioid prescription in emergency department visits:

Presented by: Vernon Pais, Jr., MD, Associate Professor of Surgery, Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine, Hanover, New Hampshire

Written by: Hanan Goldberg, MD, Urologic Oncology Fellow (SUO), University of Toronto, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Twitter: @GoldbergHanan at the American Urological Association's 2019 Annual Meeting (AUA 2019), May 3 – 6, 2019 in Chicago, Illinois

References:

1. Barnett et al. NEJM 2017

2. Poetcher et al. Drug Alcohol Dependence 2006

3. Shoag JE et al. J UROL 2019

4. Kea et al. Acad Emerg, 2016

5. Pais et al. Clin Neph 2019

6. Leapman et al. PAIN Med 2018

7. Large T et al. J UROL 2018