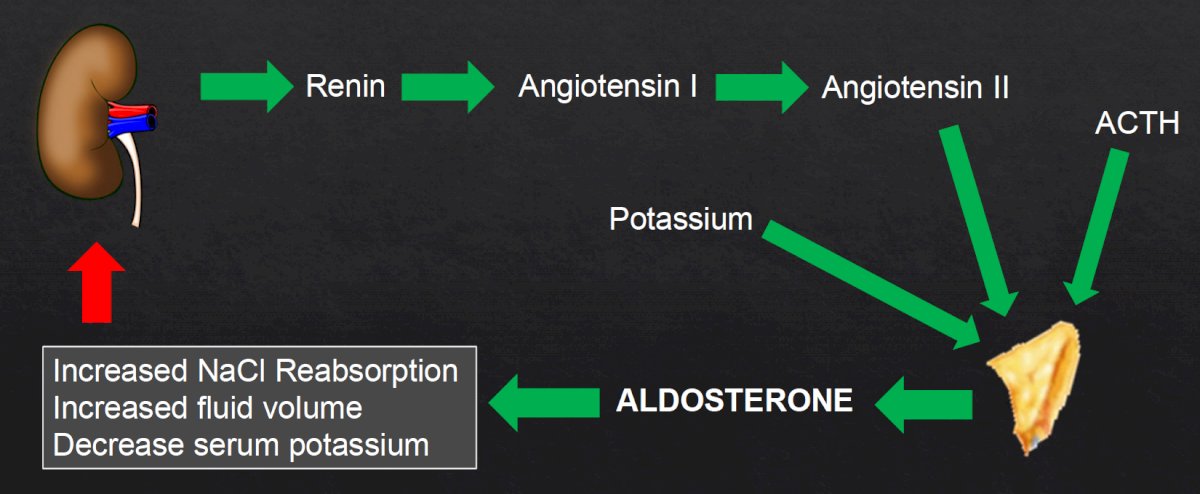

(UroToday.com) The 2021 American Urological Association (AUA) Summer School series included a session on the Evaluation and Management of Adrenal Masses moderated by Dr. Neal E. Rowe, and a presentation from Dr. Rowe discussing the management of functional adrenal tumors, specifically primary aldosteronism. Dr. Rowe notes that primary aldosteronism is also called Conn’s Syndrome, highlighted by inappropriately high aldosterone production, which is not suppressed by sodium loading. This clinical scenario results in hypertension, cardiovascular damage, and hypokalemia. The most common causes of Conn’s Syndrome include bilateral adrenal hyperplasia (60% of cases), adrenal adenoma (35% of cases), and unilateral hyperplasia (2% of cases). Rare causes are secondary to ovarian aldosterone-producing tumors, adrenocortical carcinoma, and familial hyperaldosteronism. Conn’s Syndrome is connected to the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, as highlighted in the following figure:

Dr. Rowe notes that when diagnosing and managing patients with functional adrenal masses, there are five key aspects that he uses as a guide:

- Identify patients for screening

- Screening

- Endocrinology (confirmatory tests)

- Localization

- Treatment

Indications for primary aldosteronism include clinical indications (hypertension) plus radiological indications (adrenal incidentaloma). Defining the degree of hypertension that warrants further workup by our internal medicine, cardiology, and endocrinology colleagues is quite complex and may include any of the following scenarios:

- Hypertension and a family history of primary aldosteronism

- Hypertension and hypokalemia

- BP >150/100 on three separate measurements

- BP >140/90 on three medications

- BP >140/90 on four medications

- Hypertension and a family history of cerebrovascular accident <40 years of age

- Hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea

With regards to primary aldosteronism, Dr. Rowe notes the following two clinical pearls: (i) only a minority of patients with primary aldosteronism (9-37%) demonstrate hypokalemia, and (ii) hypokalemia is an unreliable criterion to identify patients for screening with a serum aldosterone to renin ratio. Screening for primary aldosteronism includes assessing the aldosterone-to-renin ratio. In Conn’s Syndrome, autonomous aldosterone levels are high, and renin levels are low. However, there are multiple assays for both aldosterone (plasma aldosterone concentration, plasma renin activity, direct renin concentration), with cutoffs being lab-dependent. There are several medications that affect the aldosterone-to-renin ratio:

- Major impact: spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, triamterene

- Minor impact: beta-blockers, ACE-inhibitors, ARBs, dihydropyridines, K+ wasting diuretics

- Minimal impact: slow-release verapamil, hydralazine, alpha-blockers

For primary aldosteronism, confirmatory testing is done by the endocrinologist as there is no gold standard test. Several options include an oral sodium loading test, a saline infusion test, fludrocortisone suppression test, and a captopril challenge test. Important to localization is the role of a CT scan, which allows for surgical planning when needed, assesses for adrenocortical carcinoma, and identifies unilateral adenomas, bilateral adenomas, or normal adrenal gland anatomy. Subtypes of primary aldosteronism are broken down by surgically curable versus not surgically curable:

- Surgically curable: unilateral disease, aldosterone-producing adenomas (35% of cases), primary unilateral adrenal hyperplasia (2% of cases), aldosterone-producing carcinoma, and ovarian aldosterone-secreting tumor

- Not surgically curable: bilateral adrenal hyperplasia (60% of cases), familial hyperaldosteronism

A clinical pearl from Dr. Rowe regarding primary aldosteronism is that hyperaldosteronism is more likely to be from bilateral disease than unilateral disease. Adrenal vein sampling for localization is only of value in patients who are surgical candidates (since the default treatment is medical therapy), but is essential for differentiating unilateral from bilateral disease. Importantly, a CT scan can be misleading, as there can be a unilateral adenoma but bilateral hypersecretion. A systematic review previously assessed the proportion of patients with primary aldosteronism whose CT or MRI results with regard to unilateral or bilateral adrenal abnormality agreed or did not agree with those of adrenal vein sampling. Among 38 studies assessing 950 patients, in 37.8% of patients, CT/MRI results did not agree with adrenal vein sampling results. If only CT/MRI results had been used to determine lateralization of an adrenal abnormality, inappropriate adrenalectomy would have occurred in 14.6% of patients (where adrenal vein sampling showed a bilateral problem), inappropriate exclusion from adrenalectomy would have occurred in 19.1% (where adrenal vein sampling showed unilateral secretion), and adrenalectomy on the wrong side would have occurred in 3.9% (where adrenal vein sampling showed aldosterone secretion on the opposite side).

Dr. Rowe then highlighted several cases of hyperaldosteronism. The first patient was a 66-year-old male with hypertension and an incidental finding of a 2.4 cm right adrenal lesion, which based on this clinical picture would deem the patient a candidate for primary aldosteronism screening. He subsequently had an aldosterone-to-renin ratio measurement of 159 (suggestive of primary aldosteronism) and confirmatory captopril challenge test was positive. This patient underwent adrenal vein sampling with a score of 2.9 (suggesting dominance of the left adrenal), and a contralateral suppression index of 1.1 (suggesting the right adrenal is non-dominant, but not completely suppressed), with an overall interpretation of bilateral hypersecretion. The plan for this patient was medical treatment with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

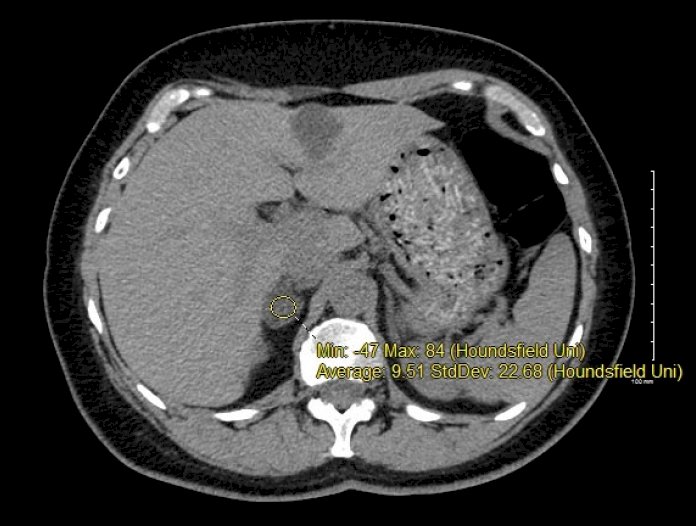

A second case included a 54-year-old female who presented to the ER with paresthesia, a history of hypertension, and a hypokalemia (K 2.2). Given the patient's hypertension and hypokalemia, she was screened with an aldosterone-to-renin ratio with a score of 176. Since her potassium was so low, with a low renin and high aldosterone, a confirmatory test was not performed. A CT scan was performed for localization, which showed a 2.3 cm right adrenal adenoma, and lateralization testing confirming right adrenal hypersecretion with contralateral suppression:

She opted for laparoscopic adrenalectomy for unilateral primary aldosteronism. This is the treatment of choice for patients who are willing to have surgery, with 100% of patients having an improvement in blood pressure and hypokalemia. Furthermore, 50% of patients are cured of their hypertension, with improved diastolic function and reversal of albuminuria. A surgical approach avoids the side-effects of medical management for primary aldosteronism, which can lead to gynecomastia, erectile dysfunction, and muscle cramps.

Dr. Rowe concluded his presentation with the following take-home messages:

- Adrenal hyperfunction is a common indication for adrenalectomy

- Thorough evaluation is critical to clarify which patients should be treated with adrenalectomy

- Most adrenal masses are amenable to minimally invasive excision

Presented by: Neal E. Rowe, MD, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Urologic Oncologist, Assistant Professor of Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University/Medical College of Georgia, @zklaassen_md on Twitter during the AUA2021 May Kick-off Weekend May 21-23.

References:

- Kempers MJE, Lenders JWM, van Outheusden L, et al. Systematic review: Diagnostic procedures to differentiate unilateral from bilateral adrenal abnormality in primary aldosteronism. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Sep 1;151(5):329-337.