(UroToday.com) The 2024 Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network (BCAN) Bladder Cancer Think Tank held in San Diego, CA was host to an implementation science session that addressed bridging evidence generation to practice in bladder cancer care. Dr. Marc Bjurlin provided an overview of smoking cessation implementation efforts for patients with bladder cancer.

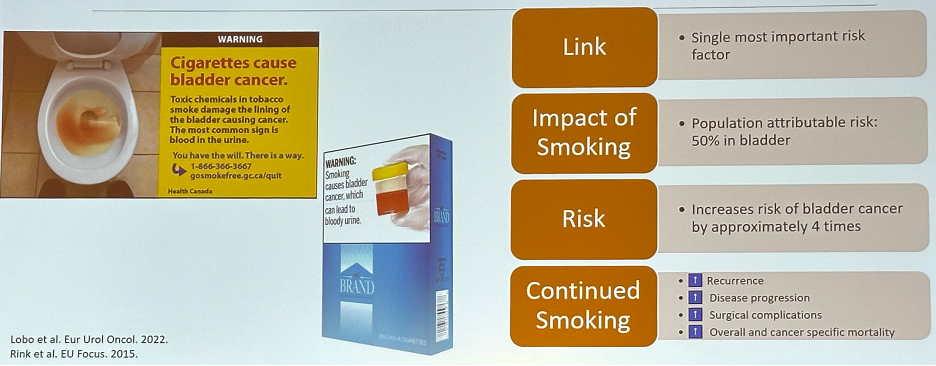

Cigarette smoking is the single most important established risk factor for bladder cancer. It is estimated that smoking accounts for ~50% of bladder cancer cases and increases the risk of bladder cancer by approximately four-fold. Significantly, continued smoking worsens:1,2

- Recurrence rates

- Disease progression rates

- Surgical complications

- Overall and cancer-specific mortality rates

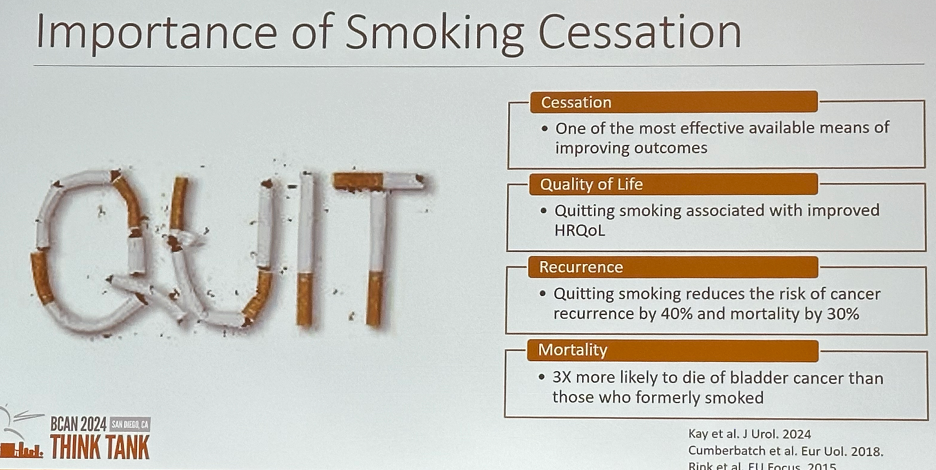

Smoking cessation is one of the most effective available means of improving outcomes. Smoking cessation is associated with improved health-related quality-of-life outcomes, 40% reduction in recurrence rates, and 30% reduction in mortality rates, with ongoing smokers 3-fold more likely to die of bladder cancer, compared to former smokers.2-4

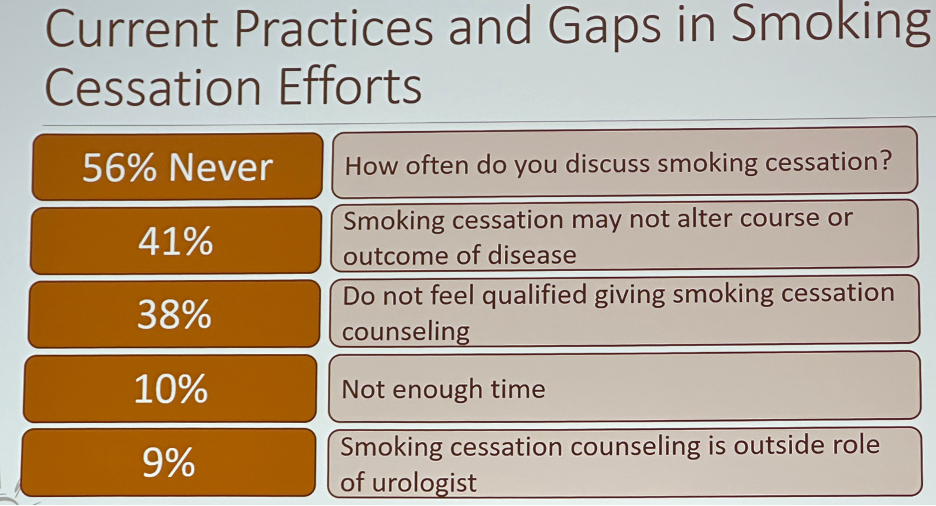

To evaluate contemporary practices and gaps in smoking cessation efforts, Dr. Bjurlin and colleagues surveyed 601 American urologists in the 2008 American Urological Association membership directory, who received a questionnaire regarding smoking cessation practice patterns. 56% of urologists reported never discussing smoking cessation, while only 20% reported always discussing smoking cessation with patients with bladder cancer. Of urologists who never discussed smoking cessation, 41% believed that smoking cessation may not alter the course or outcome of the disease, 38% did not feel qualified giving smoking cessation counseling, 10% reported not having enough time, and 9% noted that smoking cessation counseling is outside the urologist’s role.5

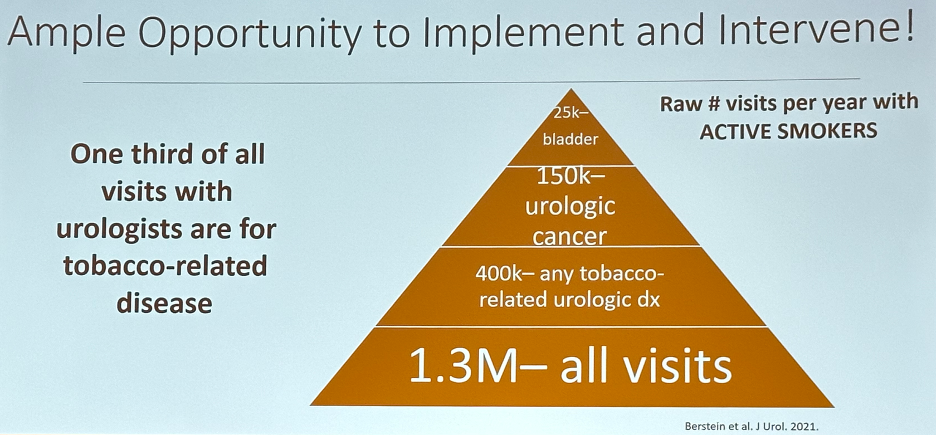

The importance of urologists engaging in smoking cessation efforts is highlighted by the results of a 2021 study by Bernstein et al. that demonstrated, using data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, that a third of all urology visits (total of 63.9 million visits over three years) were for a tobacco-related urological diagnosis and 15% were for urological cancers. An estimated 1.1 million visits over three years were with patients who identified as current tobacco users. Of all visits, 70% included tobacco screening. However, only 7% of visits with current smokers included counseling and only 3% of patients were prescribed medications.6

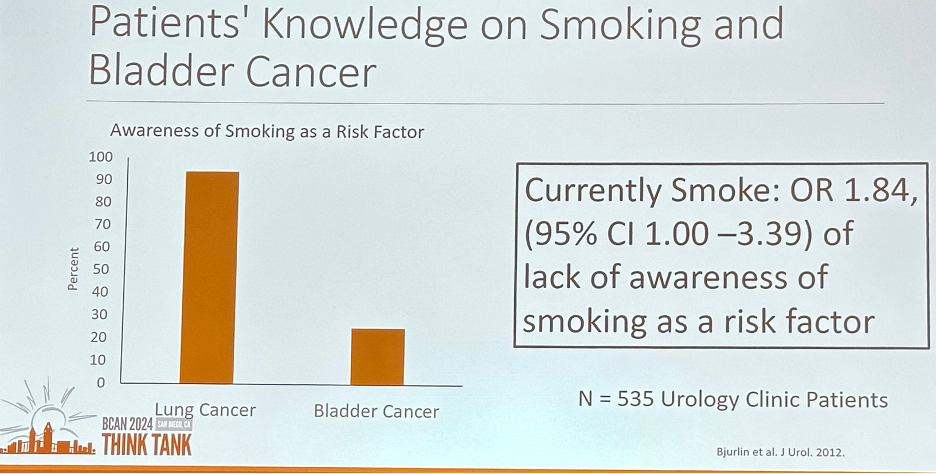

Another important barrier to smoking cessation is patients’ knowledge on smoking and bladder cancer. In a cross-sectional study of 535 patients who presented to a urology clinic over a two-year period, only 25% correctly identified smoking as a risk factor for bladder cancer. Conversely, 94% identified smoking as a risk factor for lung cancer. Current smokers were twice as likely as nonsmokers to be unaware of the link of smoking with bladder cancer.7

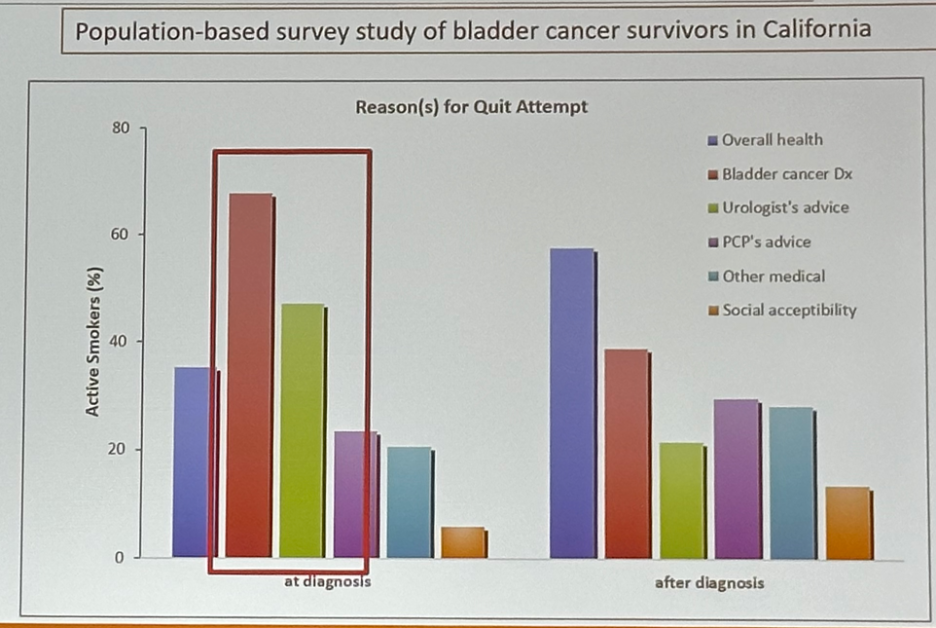

This highlights the importance of education and awareness to promote behavioral changes. In a survey of 790 bladder cancer survivors from the California Cancer Registry, Bassett et al. demonstrated that 76% of active smokers made a quit attempt, and 56% of those who attempted were successful. Success with smoking cessation was more frequent among those who attempted to quit around the time of initial bladder cancer diagnosis. Notably, the urologist’s advice was the 2nd most frequent reason for attempting smoking cessation at the time of diagnosis.8

Patients are 5-times more likely to quit smoking at bladder cancer diagnosis. The main reasons for cessation are the diagnosis itself and the urologist’s advice.9

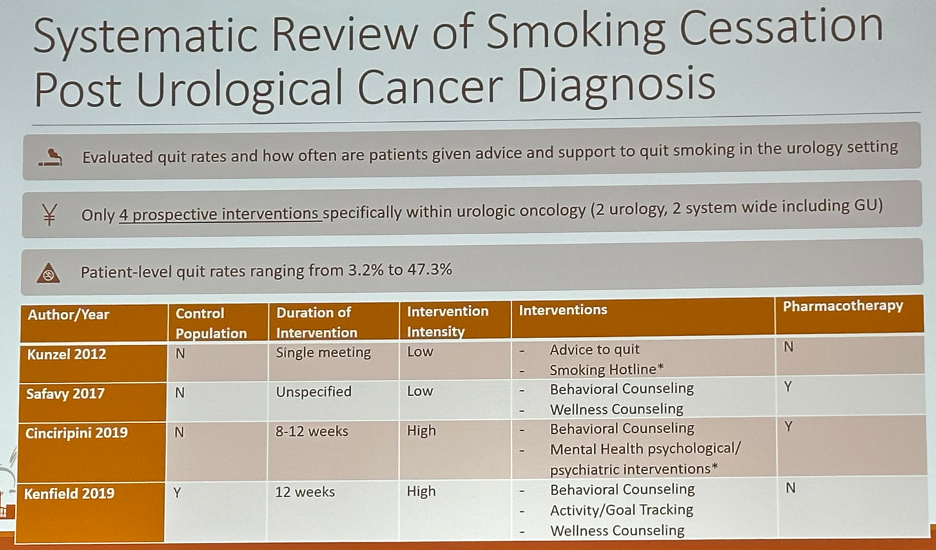

A 2021 systematic review of available studies on smoking cessation after a urological cancer diagnosis identified only four studies (n=587) that reported outcomes related to the prospective implementation of a smoking cessation program with patient-level quit rates ranging from 3.2% to 47.3%.10

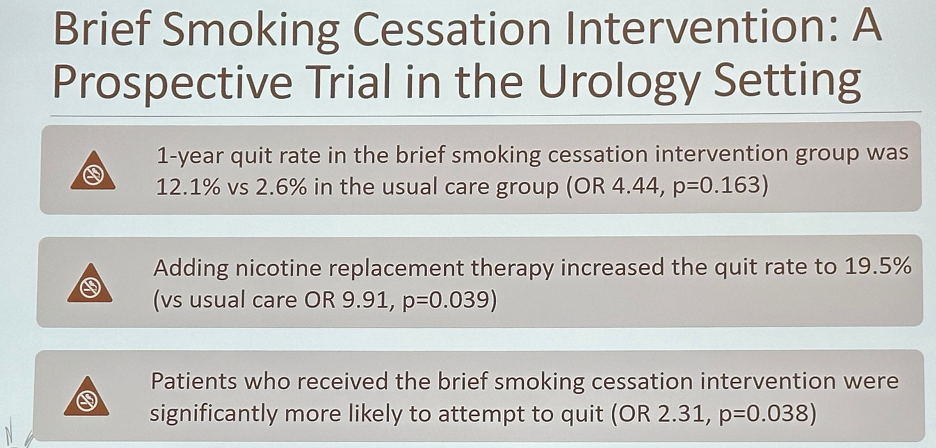

In 2013, Dr. Bjurlin and colleagues prospectively evaluated a brief smoking cessation intervention offered by a urologist at an outpatient clinic. Between 2009 and 2011 adult smokers from a single institution urology clinic were enrolled (4:1) in a prospective, brief intervention trial or in usual care as controls. All patients were assessed by the validated Fagerström test for nicotine dependence and the readiness to quit questionnaire. Trial patients received a 5-minute brief smoking cessation intervention. The primary outcome was abstinence at one year and the secondary outcome was the number of attempts to quit.

A total of 179 patients were enrolled in the study, including 100 in the brief smoking cessation intervention, 41 in the brief smoking cessation intervention plus nicotine replacement therapy and 38 usual care controls. The 1-year quit rate in the brief smoking cessation intervention group was 12% vs 2.6% in the usual care group (OR=4.44, p=0.163) Adding nicotine replacement therapy increased the quit rate to 19.5% (versus usual care: OR=9.91, p=0.039). Patients who received the brief smoking cessation intervention were significantly more likely to attempt to quit (OR=2.31, p=0.038).11

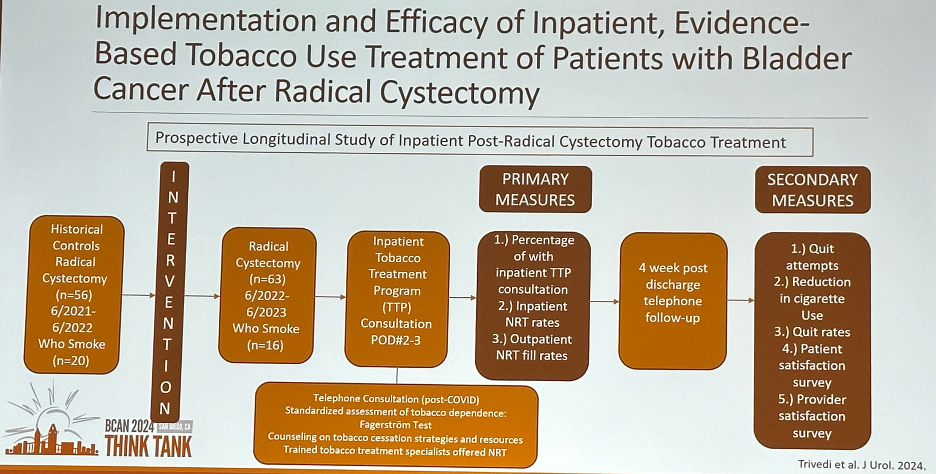

Smoking cessation efforts are not just limited to the outpatient setting. In an inpatient intervention trial, 63 radical cystectomy patients, 16 of whom were smokers at the time, participated in an inpatient tobacco treatment program on post-operative days 2–3. This program included:

- Telephone Consultation

- Standardized assessment of tobacco dependence using the Fagerström Test

- Counseling on tobacco cessation strategies and resources

- Trained tobacco treatment specialists offered nicotine-replacement therapy

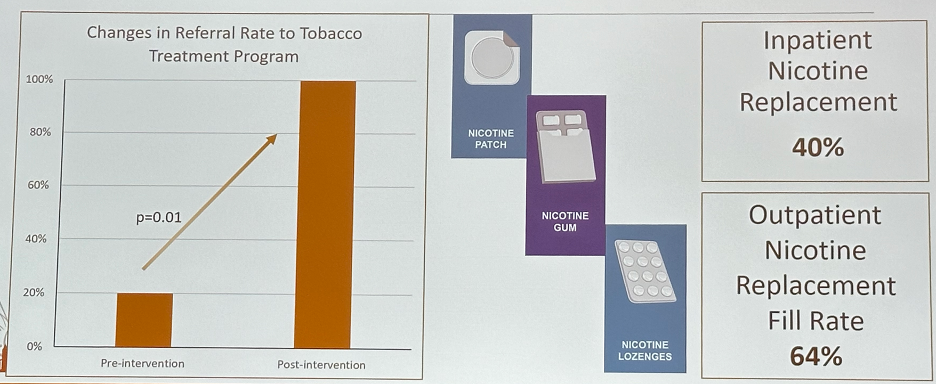

Following the intervention, all patients were referred to tobacco treatment programs. 40% received inpatient nicotine replacement, and the outpatient nicotine replacement fill rate was 64%.

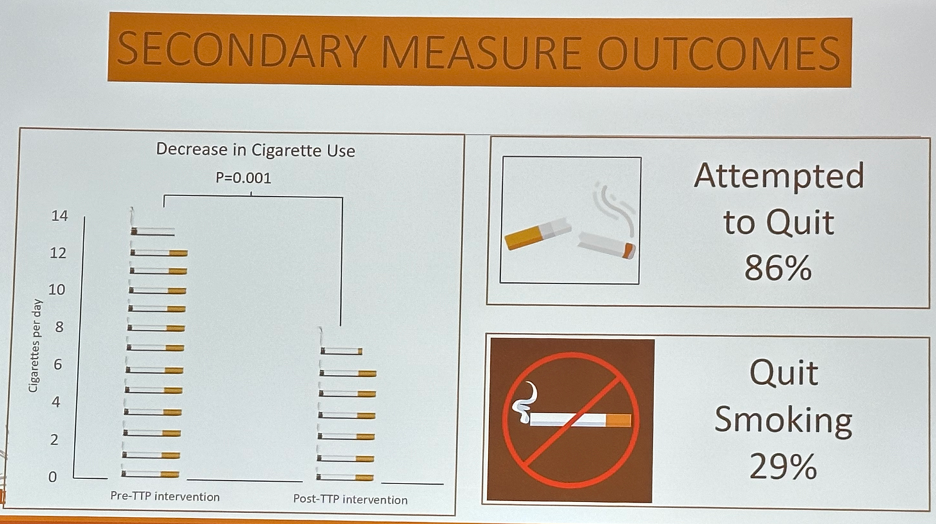

86% of patients attempted to quit smoking, and 29% actually quit.

From an implementation standpoint, physician-level identified barriers to smoking cessation include:

- Lack of time (70-78%)

- Lack of perceived patient motivation to quit smoking (44%)

- Lack of provider knowledge (42-56%)

- Lack of ancillary support (44%)

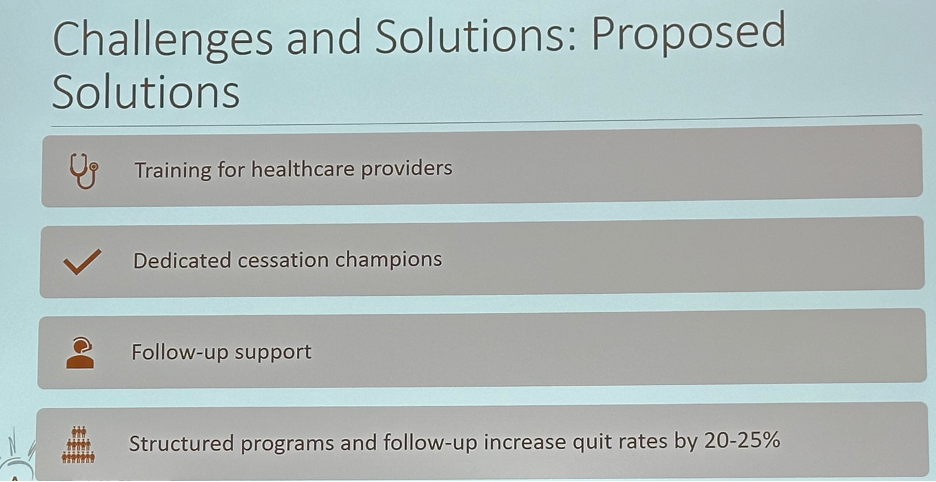

Proposed solutions to these barriers include:

- Training for healthcare providers

- Designating dedicated cessation champions

- Follow-up support

- Structured programs and follow-up to increase quit rates

Future implementation strategies in this space will include:

- Provider and patient education campaigns

- Clinical integration

- Incorporation into national bladder cancer guidelines

- Incorporation into bladder cancer therapeutic clinical trials

- Multidisciplinary collaboration

- Leads to higher success rates

- Increases cessation success by 25-35%

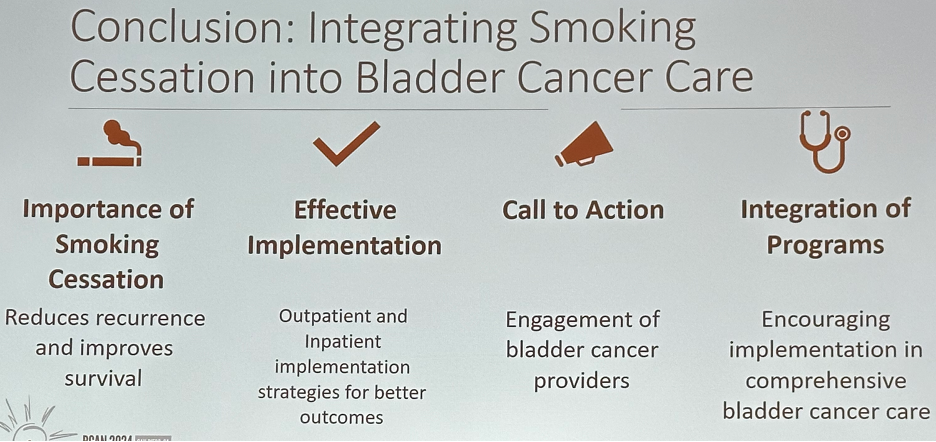

Dr. Bjurlin concluded with the following take home messages:

Presented by: Marc Bjurlin, DO, MSc, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC

Written by: Rashid Sayyid, MD, MSc – Robotic Urologic Oncology Fellow at The University of Southern California, @rksayyid on Twitter during the 2024 BCAN Bladder Cancer Think Tank held in San Diego, CA between August 7th and 9th, 2024

References:

- Lobo N, Afferi L, Moschini M, et al. Epidemiology, Screening, and Prevention of Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;5(6):628-39.

- Rink M, Crivelli JJ, Shariat SF, et al. Smoking and Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review of Risk and Outcomes Eur Urol Focus. 2015;1(1):17-27.

- Kay H, Silver S, Smith AB, et al. Bladder Cancer Survivors Who Do Not Smoke Have Better Longitudinal Health-Related Quality of Life Measures: An Assessment of the Comparative Effectiveness and Survivorship Health in Bladder Cancer (CEASE-BC) Study. J Urol. 2024;87-94.

- Cumberbatch MGK, Jubber I, Black PC, et al. Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Contemporary Update of Risk Factors in 2018. Eur Urol. 2018;74(6):784-95.

- Bjurlin MA, Goble SM, Hollowell CMP. Smoking cessation assistance for patients with bladder cancer: a national survey of American urologists. J Urol. 2010;184(5):1901-6.

- Bernstein AP, Bjurlin MA, Sherman SE, et al. Tobacco Screening and Treatment during Outpatient Urology Office Visits in the United States. J Urol. 2021;205(6):1755-61.

- Bjurlin MA, Cohn MR, Freeman VL, et al. Ethnicity and smoking status are associated with awareness of smoking related genitourinary diseases. J Urol. 2012;188(3):724-8.

- Bassett JC, Matulewicz RS, Kwan L, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Successful Smoking Cessation in Bladder Cancer Survivors. Urology. 2021;153:236-243.

- Bassett JC, Gore JL, Chi AC, et al. Impact of a bladder cancer diagnosis on smoking behavior. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1871-8.

- Zhao C, Bjurlin MA, Roberts T, et al. A Systematic Review and Scoping Analysis of Smoking Cessation after a Urological Cancer Diagnosis. J Urol. 2021;205(5):1275-85.

- Bjurlin MA, Cohn MR, Kim DY, et al. Brief smoking cessation intervention: a prospective trial in the urology setting. J Urol. 2013;189(5):1843-9.