Patients were included in this study after being identified in the Canadian Kidney Cancer information system, a prospective database of patients with RCC. Patients who received first-line VEGF-TT (sunitinib or pazopanib), and were subsequently treated with either second-line axitinib or everolimus were included in the analysis. Time to treatment failure (TTF, time from starting second-line therapy to stopping second-line therapy or loss to follow-up) and overall survival (OS, time from starting second-line therapy to death or loss to follow-up) were calculated using the Kaplan Meier method.

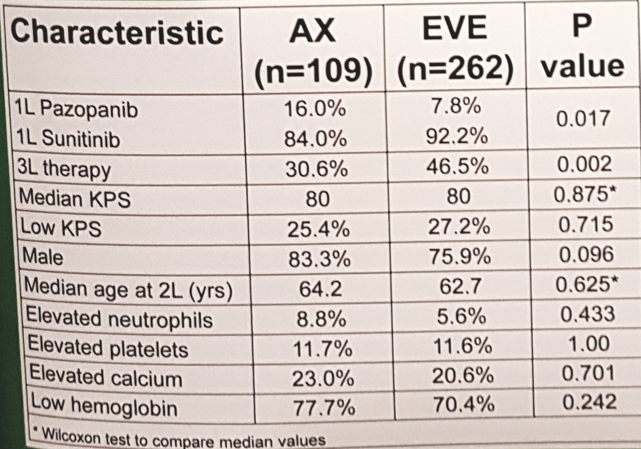

There were 1,168 patients treated with first-line VEGF-TT, including 371 patients (28.9%) that received second-line therapy: 109 (29.4%) receiving axitinib and 262 (70.6%) everolimus. Baseline characteristics are as follows:

The median TTF was greater for axitinib compared to everolimus (6.0 months vs 3.8 months; HR 0.76, 95%CI 0.62-1.00; p=0.053), however there was no significant difference in median OS between axitinib and everolimus (10.4 months vs. 14.5 months; HR 1.26, 95%CI 0.94-1.69; p=0.122). Finally, more patients received further therapy in the everolimus group than the axitinib group (47% vs 31%; p=0.002).

The strength of the current study is that it is a real-world assessment of utilization and outcomes of patients receiving available second-line therapy options among Canadian patients. A possible limitation is that this retrospective analysis may be somewhat clinically outdated moving forward given the recent findings of CheckMate 214 [1], which showed that first-line nivolumab + ipilimumab resulted in significantly improved OS outcomes compared to patients receiving sunitinib. Dr. Basappa concluded that based on this study, axitinib had a statistically better TTF than everolimus in the second line setting post-first-line VEGF-TT. Given this data, second-line axitinib should be considered an option for all patients in Canada post-first line VEGF-TT. Although the everolimus group had a better OS, this was not statistically significant and may be secondary to the everolimus group receiving more subsequent lines of therapy. Importantly, based on these results, Dr. Basappa notes that a request submitted to the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review from the Provincial Advisory Group resulted in a revised recommendation for equal access to both second-line axitinib and everolimus as of July 2017.

References:

1. Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;378(14):1277-1290.

Presented by: Naveen S. Basappa, MD, Department of Oncology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Co-Authors: Georg Bjarnason2, Aaron Hansen3, Daniel Y.C. Heng4, Anil Kapoor5, Christian Kollmannsberger6, Eric Lévesque7, Austin Kalirai8, Haocheng Li9, Ranjena Maloni10, Neil Reaume11, Denis Soulières12, Lori A. Wood13.

Author Information:

1. Department of Oncology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

2. Division of Medical Oncology/Hematology, Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

3. Division of Medical Oncology, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

4. Department of Oncology, University of Calgary, Tom Baker Cancer Centre, Calgary, AB, Canada

5. Division of Urology, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

6. Division of Medical Oncology, University of British Columbia, British Columbia Cancer Agency-Vancouver Cancer Centre, Vancouver, BC, Canada

7. University of Laval, CHUQ Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, Quebec, QC, Canada

8. University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

9. Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

10. Department Surgical Oncology (Urology), Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada

11. Division of Medical Oncology, The Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

12. Division of Medical Oncology/ Hematology, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada

13. Department of Medicine and Urology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

Written By: Zachary Klaassen, MD, Urologic Oncology Fellow, University of Toronto, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Twitter: @zklaassen_md at the 73rd Canadian Urological Association Annual Meeting - June 23 - 26, 2018 - Halifax, Nova Scotia