(UroToday.com) In this interesting debate, Dr. Tsaur presented a case of a 63-year-old man who initially underwent robotic radical prostatectomy with pathology showing a pT3bN0M0 Gleason 7 disease with an initial PSA of 18 ng/ml.

Following surgery, his prostate-specific antigen (PSA) began to rise from 0.9 to 1.9 ng/ml. The PSA doubling time was calculated as 5.2 months. The patient underwent a CT scan without any evidence of metastases. He underwent salvage radiotherapy to the pelvic lymph nodes with 45 Gy overall dose + 20 Gy boost to the prostate bed without receiving ADT.

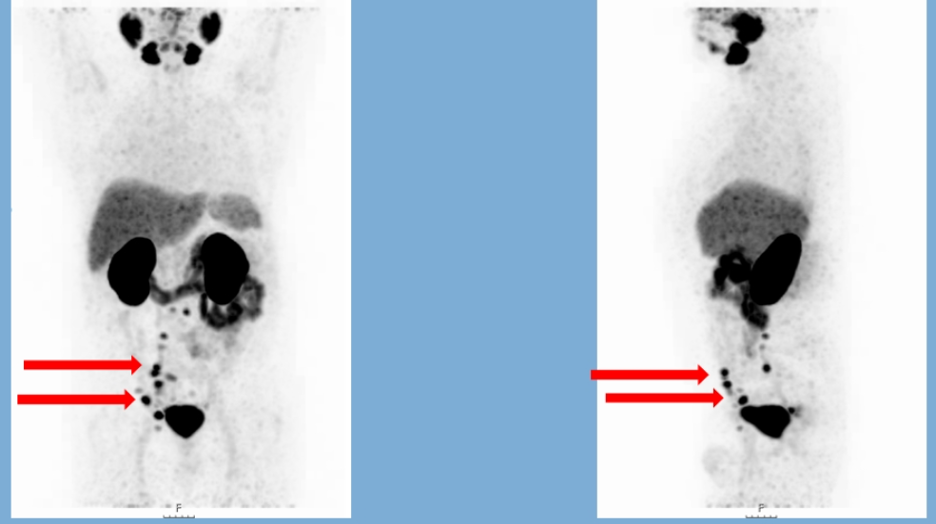

Six months later, his PSA went up to 7 ng/ml, and he received androgen deprivation therapy. A few months later, he presented with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and a PSA of 6.7 ng/ml. The patient remained active, and a new CT scan showed lymph nodes measuring up to 1 cm with no obvious metastatic lymph nodes. He also had a bone scan at this time, showing debatable metastatic nodes in the pelvis. The patient later underwent a PSMA-PET/CT showing uptake in multiple lymph nodes in the right hypogastric, epigastric, and paraaortic region, with no visceral or bone metastases (figure 1).

Figure 1 – 68-GA-PSMA PETCT images of the patient:

The patient later received docetaxel 6 cycles 75mg/qm, and his PSA came down to 2.6 ng/ml. Several months later, his PSA went up again to 16 ng/ml, and a new CT scan demonstrated lymph node progression. At this point, he started receiving treatment with abiraterone, and his PSA came down to 7 ng/ml.

Six months later, his PSA started to rise again to 26 ng/ml, and a new CT and bone scan were done demonstrating lymph node progression and new bone disease (axial skeleton + ribs).

At this point, he started receiving treatment with cabazitaxel bringing his PSA down to 15 ng/ml. Unfortunately, his PSA began to rise again to a level of 42 ng/ml. The patient underwent another PET PSMA scan, demonstrating lymph node and bone disease progression, and he also became mildly symptomatic (figure 2). A summary figure demonstrating all the treatments he received up to this point is shown in figure 3.

Figure 2 – PET PSME CT scan after progression:

Figure 3 – Summary of all treatments received:

Dr. Tsaur concluded his case presentation showing the various treatment options that are available at this point according to him:

- Enzalutamide

- Radium -223

- Docetaxel re-challenge

- PSMA radioligand therapy

- Cabazitaxel/ carboplatin

- Olaparib or pembrolizumab (after performing targeted sequencing searching for somatic genetic alterations)

In the next part of this session, Dr. Vogel, the medical oncologist, presented her perspective on how she believes this patient should be treated.

The recently published CARD study1 randomized 255 patients with mCRPC to either cabazitaxel or androgen signaling targeted inhibitors (abiraterone or enzalutamide). The median progression-free survival was in favor of cabazitaxel (8 months vs. 3.7 months) with a similar percentage of adverse events (38.9% vs. 38.7%).

According to Dr. Vogel, there are two strategies for this patient. We can either use what is left or dig deeper and choose wisely. If we choose to use what is left, then enzalutamide is a good option with a probable PSA response of 9-22%, with a progression-free survival of fewer than 4.6 months in docetaxel and abiraterone pretreated patients, such as this one.

Another option is to use radium-223 due to his mildly symptomatic bone disease, or we can give another re-challenge with docetaxel, although there is no data regarding the use of docetaxel after progression on cabazitaxel.

Dr. Vogel believes that it is better to dig deeper, perform some more investigations, and see if we can treat this patient better and more accurately.

First, she recommended performing testing for somatic genetic alterations for BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, BRIP1, BARD1, CDK12, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANCL, PALB2, PPP2R2A, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, RAD54L, and microsatellite instability.

It would also be prudent to consider the option or rebiopsy of the patient, as his last pathologic report was eight years ago.

It is also recommended to use new-generation imaging (preferably PET PSMA) to see if Lutetium therapy can perhaps be utilized.

Lastly, Dr. Vogel would recommend checking for adverse features such as low PSA, visceral metastases, the short response to ADT, and testing for neuron-specific enolase for neuroendocrine features.

If somatic alterations are found, then the use of PARP inhibitors would be recommended, as shown by the previous data2.

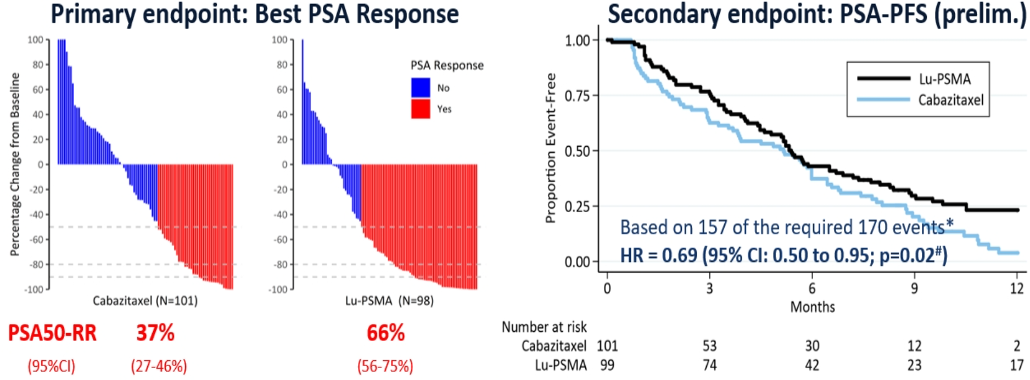

Lastly, we must consider the option of Lutetium therapy with results from the phase 3 VISION trial (NCT03511664) still pending. This trial compares lutetium therapy to cabazitaxel therapy in mCRPC patients, with preliminary results presented in ASCO 2020 (Figure 4), showing a PSA progression-free survival benefit for Lutetium treated patients.

Figure 4 – VISTA trial preliminary results:

In the next part of this debate, Dr. Eiber gave the perspective of the nuclear medicine specialty.

In the LuPSMA trial3, which was a single-center, single-arm phase 2 trial examining the effect of Lu-PSMA-617 radionuclide treatment in patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer, 87% and 40% of the patients had already received docetaxel and cabazitaxel, respectively. Moreover, 83% of the cohort received either abiraterone and/or enzalutamide. The results were quite impressive, demonstrating a 57% >50% PSA response rate, with benefit in overall survival and pain improvement as well (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – LuPSMA trial results:

In the TheraP study4, which was a randomized phase 2 trial of LU-PSMA-617 theranostic vs. cabazitaxel in progressive metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer, patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either cabazitaxel or LU-PSMA-617 (figure 6). In this trial, the results demonstrated a significant advantage again to LU-PSMA which had a 29% higher PSA>=50% response rate compared to cabazitaxel (figure 7) with pending results of radiographic progression-free survival and overall survival.

Figure 6- TheraP trial design:

Figure 7- TheraP trial results:

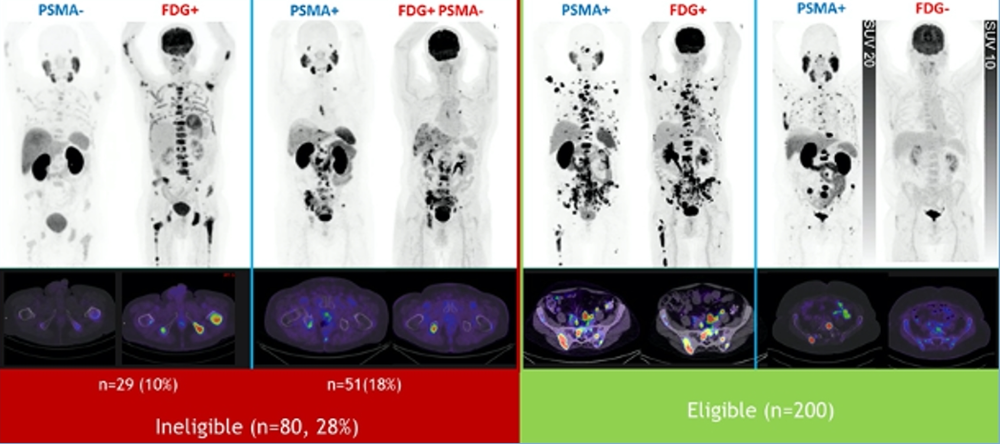

Although PSMA-PET is routinely used for screening prior to therapy administered with LU-PSMA, there is still no consensus on what is defined as “adequate uptake.” Therefore, there are different approaches that have been used:

- “Clinical routine” – higher than the liver, no PSMA-negative liver/large soft tissue lesions – estimated 5-10% who are ineligible

- At dominant tumor sites SUVmax 1.5 times SUVmean of the liver – 16.3% ineligible

- TheraP criteria – PSMA SUVmax>20 at any site, measurable sites SUVmax >10, no PSMA-/FDG positive disease – 28% ineligible

It is not clear if patients need to be positive only on PET-PSMA and either positive or negative on FDG (Figure 8).

Figure 8 – PSMA-PET only vs. PSMA plus FDG-PET:

Dr. Eiber ended his talk with some details on the future directions that are being explored. He mentioned a new alpha emitter treatment with AC-PSMA-617 PSMA-targeted alpha radiation therapy that has been used in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer, showing good responses and correlated with disease stage (Figure 9).

Figure 9 – Ac-225 PSMA radioligand therapy:

Dr. Eiber concluded his talk, reiterating that LU-PMA is a safe and well-tolerated treatment modality in a 3+ line of treatment in mCRPC patients. Phase 2 data are very promising, including a comparison to cabazitaxel. The ongoing phase 3 VISION trial is eagerly awaited.

The selection of imaging seems critical, but the implementation in clinical practice remains unclear.

In the last part of this debate, Dr. Heidenreich, the Urologist, presented his perspective on the treatment of this patient.

According to him, this is a classical clinical scenario of end-stage disease following multiple systemic therapies. It seems that LU-PSMA is the last straw in the treatment cascade with limited therapeutic efficacy. Dr. Heidenreich believes that the implementation of LU-PSMA earlier in the progression of mCRPC might result in an improved oncological outcome.

High-risk localized prostate cancer has been shown to be associated with PSA relapse in 40-60% of cases following radical prostatectomy, which in turn, is associated with increased prostate cancer-specific mortality. There are several scientific approaches for these high-risk patients:

- Neoadjuvant ADT for 3-8 months: has shown to induce a reduction of positive surgical margins but no benefit in oncological outcome

- Neoadjuvant ADT and bicalutamide, ketoconazole, and dutasteride. This has shown to result in a complete pathological response in 5.7% of cases with a residual tumor in 25.7% of cases

- When treating with neoadjuvant ADT with abiraterone, it has been shown to bring down tissue levels of testosterone, DHT, DHEAS, and androstenedione, when compared to ADT alone in the neoadjuvant setting5.

Another option is neoadjuvant LU-PSMA treatment. The rationale for this type of treatment is several folds:

- Prognostic significance of PSMA expression in prostate biopsies

- Mode of action of LU-PSMA

- High PSMA expression in Gleason score 8-10 prostate cancer

- High PSMA expression in lymph node metastases

PSMA expression in prostate biopsies has been used for risk stratification at the time of initial diagnosis6. It was shown that PSMA expression was significantly associated with grade group and initial PSA level. Elevated PSMA expression on both radical prostatectomy and biopsy tissues significantly correlated with increased risk of disease recurrence with 88.2%, 74.2%, 67.7%, and 26.8% recurrence rates in no, low, medium and high levels of PSMA expression, respectively. Interestingly, elevated PSMA levels in the biopsy tissue predicted a 4-fold increased risk of disease recurrence, independent from initial PSA and grade group on biopsy6.

PSMA expression has been shown to be increased in patients with Pt3, and positive lymph node disease, not independent from PSA and Gleason score. On multivariable analysis, PSMA expression, positive lymph node disease, and extraprostatic extension were associated with disease relapse7.

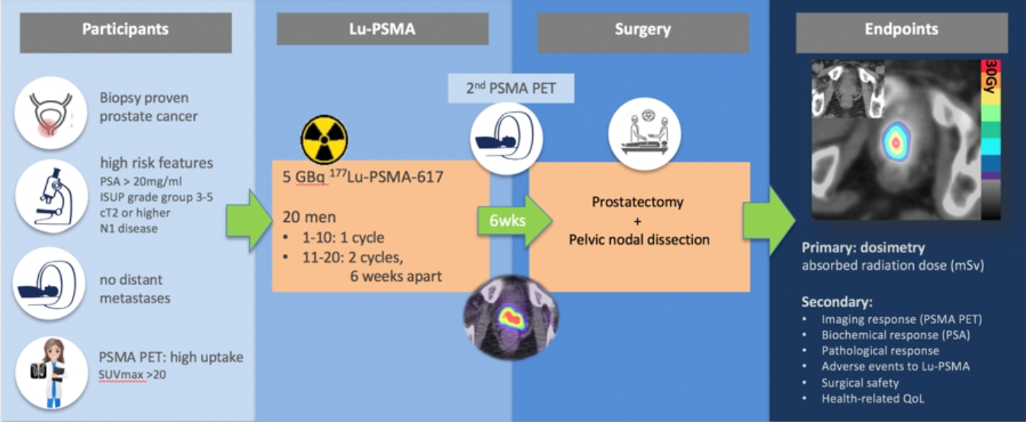

LU-PSMA use as neoadjuvant therapy will be assessed in the LUTECTOMY clinical trial (Figure 10). In this trial, patients with high-risk prostate cancer will receive neoadjuvant LU-PSMA treatment for 6 weeks and then undergo radical prostatectomy + pelvic lymph node dissection. The primary endpoint will be dosimetry, while secondary endpoints include imaging response, biochemical response, pathological response, adverse events, surgical safety, and health-related quality of life.

Figure 10 - LUTECTOMY clinical trial design:

Adjuvant radionuclide therapy can also be an option, as has been used in other neoplasms. In a study assessing the use of LU-PSMA in patients with M1 disease (lymph node only), the maximum median PSA decline was 92%8.

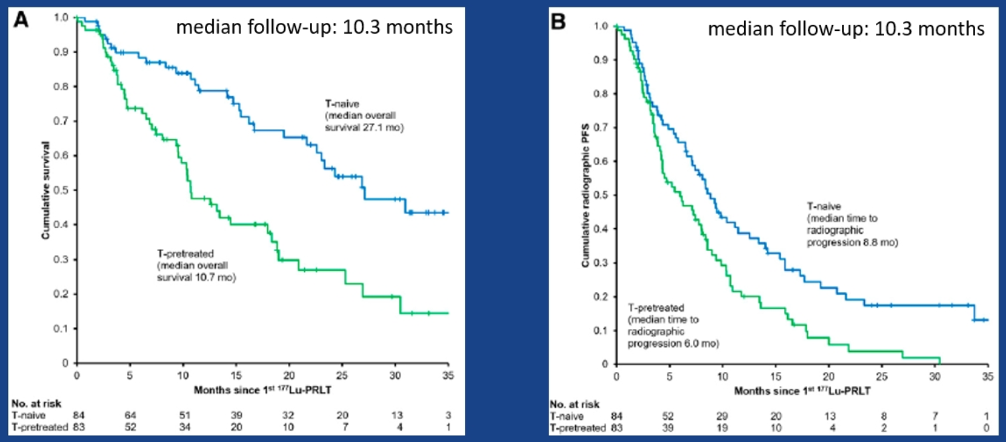

LU-PSMA can be given as 2nd line therapy after ADT, as radionuclide therapy seems to be more effective if integrated early in the therapeutic pathway9. Early use of LU-PSMA seems to also have a greater beneficial effect when compared to patients who were first treated with taxanes and only then with LU-PSMA10 (Figure 11). These are very promising results, but it is important to remember that these are based on mainly single-center case series.

The last topic discussed was the use of LU-PSMA as salvage therapy in relapsing disease.

The TheraP trial compared LU-PSMA with cabazitaxel in mCRPC patients (Figure 6) with the results demonstrating significant benefit to LU-PSMA treated patients over those treated with cabazitaxel (Figure 7).

In conclusion, the use of LU-PSMA should be the standard of care in mCRPC patients who fail approved therapies or who exhibit contraindications. There are promising prospective trials performed with moderate PSA response and moderate toxicity profile. Lastly, there is still a lack of evidence from clinical phase 3 trials using standardized oncological endpoints such as radiographic progression-free survival and/or overall survival.

Figure 11 – Early use of LU-PSMA (before vs. after taxane treatment):

Presented by:

Igor Tsaur, MD, of Mainz University Medicine in Mainz, Germany

Ursula Vogel, MD, PhD, Medical Oncologist at Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale (EOC), Bellinzona, Switzerland

Matthias Eiber, MD, PhD,Technische Universität München | TUM · Nuklearmedizinische Klinik und Poliklinik, Berlin, Germany

Axel Heidenreich, MD, University of Cologne, Department of Urology, Germany

Written by: Hanan Goldberg, MD, MSc., Urology Department, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, USA, @GoldbergHanan at the Virtual 2020 EAU Annual Meeting #EAU20, July 17-19, 2020.

References:

1. de Wit R, de Bono J, Sternberg CN, et al. Cabazitaxel versus Abiraterone or Enzalutamide in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2019; 381(26): 2506-18.

2. de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2020; 382(22): 2091-102.

3. Hofman MS, Violet J, Hicks RJ, et al. [(177)Lu]-PSMA-617 radionuclide treatment in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (LuPSMA trial): a single-centre, single-arm, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology 2018; 19(6): 825-33.

4. Hofman MS, Emmett L, Violet J, et al. TheraP: a randomized phase 2 trial of (177) Lu-PSMA-617 theranostic treatment vs cabazitaxel in progressive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (Clinical Trial Protocol ANZUP 1603). BJU international 2019; 124 Suppl 1: 5-13.

5. Taplin ME, Montgomery B, Logothetis CJ, et al. Intense androgen-deprivation therapy with abiraterone acetate plus leuprolide acetate in patients with localized high-risk prostate cancer: results of a randomized phase II neoadjuvant study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2014; 32(33): 3705-15.

6. Hupe MC, Philippi C, Roth D, et al. Using PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen) evaluation on prostate biopsies for risk stratification at time of initial diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019; 37(7_suppl): 6-.

7. Perner S, Hofer MD, Kim R, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen expression as a predictor of prostate cancer progression. Human pathology 2007; 38(5): 696-701.

8. von Eyben FE, Singh A, Zhang J, et al. 177 Lu-PSMA radioligand therapy of predominant lymph node metastatic prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2019; 10(25).

9. Heidenreich A, Gillessen S, Heinrich D, et al. Radium-223 in asymptomatic patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases treated in an international early access program. BMC Cancer 2019; 19(1): 12.

10. Barber TW, Singh A, Kulkarni HR, Niepsch K, Billah B, Baum RP. Clinical Outcomes of (177)Lu-PSMA Radioligand Therapy in Earlier and Later Phases of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Grouped by Previous Taxane Chemotherapy. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2019; 60(7): 955-62.