(UroToday.com) The 2024 European Association of Urology (EAU) annual congress held in Paris, France between April 5th and 8th was host to a joint session of the EAU, EANM, ESMO, and ESTRO addressing the collaborative management of patients with stage II seminoma. Dr. Zachary Klaassen delivered a state-of-the-art lecture discussing the long-term toxicity of treatment in adolescents and young adults with testicular cancer.

While cisplatin-based chemotherapy (bleomycin-etoposide-cisplatin [BEP]) has proven survival benefits for patients with advanced stage testicular cancer, there is a real ‘cost’ to chemotherapy for such young survivors. In an analysis of 1,214 testicular cancer patients ≤55 years of age at diagnosis, with a median follow-up duration of 4.2 years, six significant adverse health outcomes clusters were identified:

- Hearing loss/damage and tinnitus (Odds Ratio [OR]: 16.3)

- Hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes (OR: 9.8)

- Neuropathy, pain, Raynaud phenomenon (OR: 5.5)

- Cardiovascular and related conditions (OR: 5.0)

- Thyroid disease and erectile dysfunction (OR: 4.2)

- Depression/anxiety and hypogonadism (OR: 2.8)

Notably, the cumulative burden of morbidity among these survivors was rated as high, very high, or severe in approximately 20% of patients. For comparison, only 5% of patients had no cumulative burden of morbidity. This highlights that such patients are 4-fold more likely to report severe comorbidity burden versus no burden at all.1

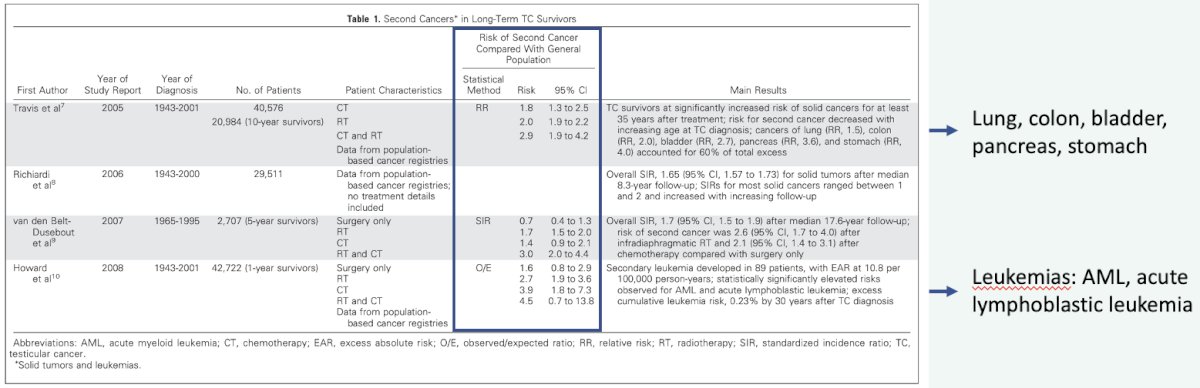

Another real concern with these patients is the risk of secondary malignancies, including lung, colon, bladder, pancreas, stomach, and leukemia (increased risks up to 4.5-fold).2

These patients are additionally at risk of hypogonadism. As summarized in the bar graph below, patients receiving cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy are at increased risk of hypogonadism requiring androgen replacement therapy. This risk appears to be correlated to the cumulative dose of cisplatin received with a further increased risk among patients who had cumulatively received >850 mg of cisplatin.2

In addition to the adverse pathophysiologic outcomes with chemotherapy, there are important secondary psychological effects that cannot be underestimated. In 2021, Raphael et al. published the results of a population-based retrospective cohort study from Ontario, Canada that included all incident testis cancer cases from 2000 to 2010, identified using the Ontario Cancer Registry. The investigators utilized validated codes for mental health utilization both on an outpatient basis and within emergency department/hospitalization settings. The baseline period was defined as one month to two years prior to orchiectomy, peri-treatment as one month before and after orchiectomy, and post-chemotherapy as the period ≥1 month following orchiectomy. 2,619 testicular cancer cases were matched to 13,095 controls. Importantly, there was no baseline difference in the rate of mental health service use between cases and controls. Cases were significantly more likely than controls to have an outpatient visit for a mental health concern in the peritreatment (adjusted RR [aRR]: 2.45; 95% CI: 2.06–2.92) and post-treatment periods (aRR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.12–1.52). The difference in mental health service use persisted over a median follow-up of 12 years. In the post-orchiectomy period, cases with baseline mental health service use were those most likely to use mental health services (aRR: 5.64; 95% CI: 4.64–6.85).3

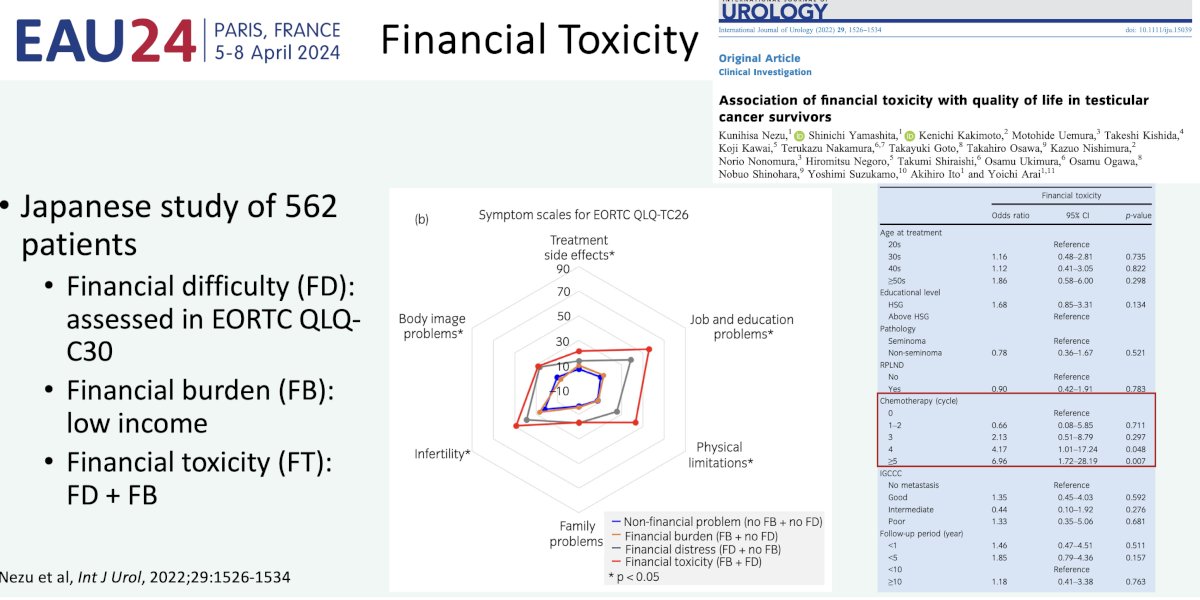

Another important consideration for these survivors is the financial toxicity component. Over the past decade, there has been improved recognition of financial toxicity among cancer survivors, which has been shown to be associated with worse quality of life outcomes, symptoms/pain, and cancer outcomes. This was recently demonstrated in a Japanese cohort of testicular cancer survivors, with patients experiencing severe financial difficulty having more treatment side effects, physical limitations, and anxiety concerning employment and future. Reasons for this financial toxicity among testicular cancer survivors include:

- Young age at diagnosis

- In school (no income) or working (interruption of income)

- Survivors may have young children (cost of dependents)

- Increased number of chemotherapy cycles (≥4 versus ≤4 cycles: Odds ratio of 4.17 for outcome of financial toxicity)4

What about premature mortality in such patients? A registry trial from Norway of 9,541 testicular cancer patients diagnosed between 1953 and 2015 demonstrated that during follow-up, 80% of deaths are due to testicular cancer within 5 years of diagnosis. Non-testicular secondary malignancies were most commonly due to gastric, pancreatic, and bladder cancer which accounted for ~65% of excess non-testicular cancer deaths. Cardiovascular disease accounted for 9% of excess non-testicular cancer deaths. Notably, a diagnosis after 1989 was associated with an increased rate of suicide mortality.5

These findings were corroborated in a Norwegian population-level analysis of 5,707 patients diagnosed between 1980 and 2009. In this cohort, the non-testicular cancer mortality rate was increased by 23% in patients who received platinum-based chemotherapy, by 28% in those who received radiotherapy, and by 65% in those who received both modalities.6

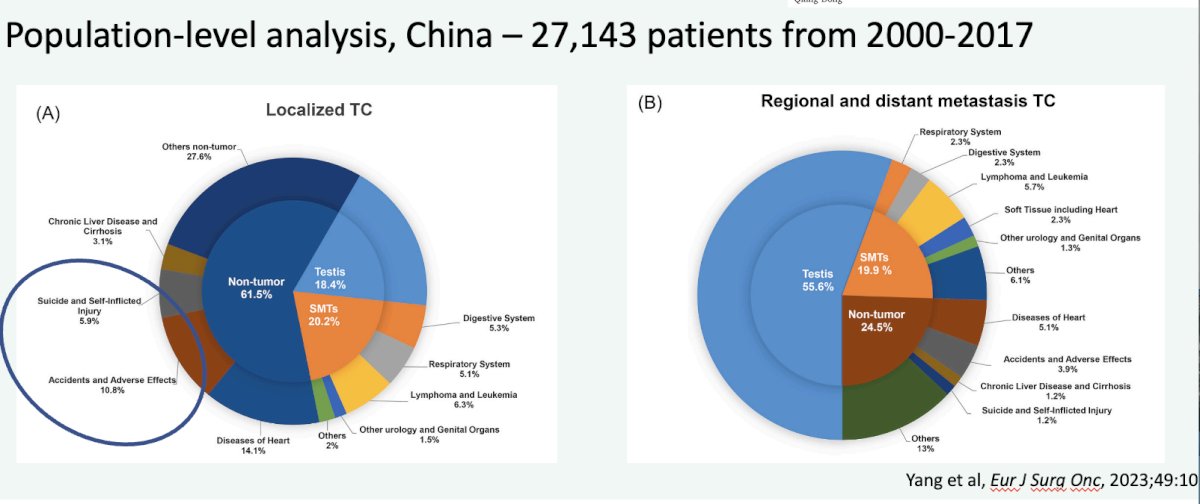

Another concerning cause of non-testicular deaths appears to be suicide and self-inflicted injuries as demonstrated in a Chinese population-level analysis. Notably, an additional 10.8% of patients experience non-testicular mortality, secondary to accidents and adverse effects.

How can we improve these patients’ quality of life? While we cannot control the toxicity from chemotherapy or the age these men are diagnosed, there are numerous factors that we can control:

- Ensuring each patient has a primary care provider: cancer screening, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, etc.

- Using surveillance when appropriate (Clinical Stage I germ cell tumors)

- Screening for distress

- This can be accomplished using the NCCN Distress Management questionnaire that can be easily administered during a clinic visit

- Tempering psychological morbidity

The involvement of a multi-disciplinary team to provide comprehensive care for these patients (psychologic, social, clinical) is crucial for optimizing these patients’ outcomes.

Dr. Klaassen concluded his presentation as follows:

- Testicular cancer patients are young at diagnosis, with generally excellent survival after treatment

- Treatment leads to both a myriad of short- and long-term physical morbidity

- Psychological morbidity is often long-lasting, leading to increased utilization of mental health resources

- Financial toxicity needs to be further explored – worse physical symptoms, job and education issues, and associated with cumulative doses of chemotherapy

- Non-testicular cancer death is the most common cause of mortality after 5 years: secondary malignancies, cardiovascular disease, suicide, etc.

- We need to be vigilant! Advocate for our patients regarding what we can control

Presented by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, Wellstar MCG Health, Augusta, GA

Written by: Rashid Sayyid, MD, MSc - Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Clinical Fellow at The University of Toronto, @rksayyid on Twitter during the 2024 European Association of Urology (EAU) annual congress, Paris, France, April 5th - April 8th, 2024

Related content: Long-Term Toxicity in Testicular Cancer and AYA: Premature Mortality and Morbidity Illustrated - Zachary Klaassen

- Kerns SL, Fung C, Monahan PO, et al. Cumulative Burden of Morbidity Among Testicular Cancer Survivors After Standard Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy: A Multi-Institutional Study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15): 1505-1512.

- Haugnes HS, Bosl GJ, Boer H, et al. Long-term and late effects of germ cell testicular cancer treatment and implications for follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30): 3752-3763.

- Raphael MJ, Gupta S, Wei X, et al. Long-Term Mental Health Service Utilization Among Survivors of Testicular Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7): 779-786.

- Nezu K, Yamashita S, Kakimoto K, et al. Association of financial toxicity with quality of life in testicular cancer survivors. Int J Urol. 2022;29(12): 1526-1534.

- Kvammen Ø, Myklebust TA, Solberg A, et al. Causes of inferior relative survival after testicular germ cell tumor diagnosed 1953-2015: A population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14(12): e0225942.

- Hellesnes R, Myklebust TA, Fossa SD, et al. Testicular Cancer in the Cisplatin Era: Causes of Death and Mortality Rates in a Population-Based Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(32): 3561-3573.