(UroToday.com) The Realizing Potential Combination and Personalized Therapy educational session at the European Society of Medical Oncology’s (ESMO) 2021 congress included a presentation by Dr. Manuela Schmidinger discussing the current status of personalized therapy in metastatic RCC. Dr. Schmidinger notes that the reason we need personalized therapy in metastatic RCC is that there are currently four competing strategies for IMDC intermediate-poor risk patients and three options for favorable risk. Given the wealth of novel treatment options, multiple questions arise: (i) what is the role of single-agent TKI? In favorable-risk patients there is no OS advantage for single-agent TKI, however, the complete response rate is twice as high; (ii) If ICI-based therapies are the backbone, should we be offering ICI doublets or ICI/TKI combination therapy? (iii) If we are using ICI-only treatment, does it always mean it has to be a doublet? (iv) If ICI/TKI double therapy, which TKI should we use? (v) Do some patients need something totally different than the current clinical trials we have?

The current status of research in personalized medicine for metastatic RCC according to Dr. Schmidinger is as follows:

PD-L1 is a prognostic biomarker and not predictive, however, the PD-L1 interpretation remains challenging. If your patient is PD-L1 positive, it means that they will likely have poor outcomes from single-agent TKI, whereas ICI-based treatments improve outcomes irrespective of PD-L1 expression, and that expression may be associated with improved hazard ratios for PFS and ORR. With regards to neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), this biomarker is also prognostic and not predictive, whereby a change in NLR on treatment could serve as an on-treatment predictive factor, for example, a change in NLR between 4-8 weeks post-treatment initiation:1

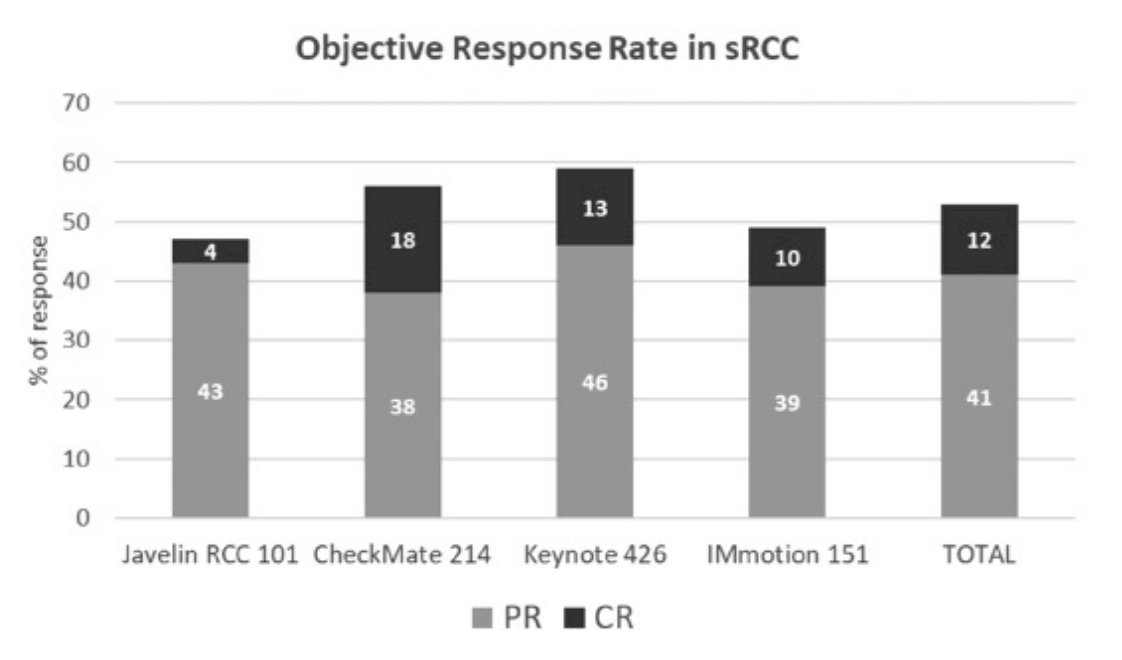

For sarcomatoid differentiation, these tumors are more likely to have PD-L1 co-expressed and likely have more benefit when treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. In IMmotion151, 61% of patients with sarcomatoid features were classified as PD-L1 positive.2 In the CheckMate 214 trial,3 patients with sarcomatoid features had a median OS with nivolumab + ipilimumab that was not yet reached (95% CI 25.2 months to not-reached) versus sunitinib of 14.2 months (95% CI 9.3-22.9) with a hazard ratio of 0.45 (95% CI 0.3-0.7). For PFS, this also favored the nivolumab + ipilimumab arm (26.5 months versus 5.1 months) with a hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% CI 0.33-0.86). In the CheckMate 9ER trial4 of nivolumab + cabozantinib, the median PFS was 17.0 months (95% CI 12.6-19.4) compared to sunitinib 9.3 months (95% CI 6.9-9.7) with a hazard ratio of 0.52 (95% CI 0.43-0.64). As follows is a summary of ORR for sarcomatoid RCC across the trials:5

There are several potential biomarkers available that have yet to be established in the clinical setting, including the tumor microenvironment, INDELS, and genetic alterations, as summarized below:

Work from 2015 suggested that there are molecular subtypes of clear cell RCC that are associated with response to sunitinib.6 This analysis identified 4 robust ccRCC subtypes (ccrcc1 to 4) related to previous molecular classifications that were associated with different responses to sunitinib treatment. ccrcc1/ccrcc4 tumors had a lower response rate and a shorter PFS and OS than ccrcc2/ccrcc3 tumors):

Additionally, ccrcc1/ccrcc4 tumors were characterized by a stem-cell polycomb signature and CpG hypermethylation, whereas ccrcc3 tumors, sensitive to sunitinib, did not exhibit cellular response to hypoxia. Furthermore, ccrcc4 tumors exhibited sarcomatoid differentiation with a strong inflammatory, Th1-oriented but suppressive immune microenvironment, with high expression of PDCD1 (PD-1) and its ligands.

Important data has also been generated from tumors of patients in the IMmotion 150 and 1512 trials, specifically a 3-gene panel for mRNA quantification: Angio/Teff/Myeloid inflammation signature, with predictive responses to TKI and ICI:

In the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial of avelumab + axitinib versus sunitinib, the 26-gene JAVELIN Renal signature was comprised of TcR signaling, Tcell activation/proliferation/differentiation, NK cell-mediated toxicity, and other immune genes, providing prediction of improved PFS with avelumab + axitinib, but not sunitinib. This was also verified in an independent data set from the phase 1b JAVELIN Renal 100 cohort.7 The gene expression signatures from the IMmotion 150 and JAVELIN Renal 101 trial were also assessed in the CheckMate 214 trial, noting that the Anghigh signature predicted ORR and PFS for sunitinib, Anglow signature had a higher ORR for nivolumab + ipilimumab, whereas the Teff signatures from IMotion and JAVELIN were not associated with benefit. However, patients with PFS >18 months had a higher expression of genes related to inflammatory response and EMT. Finally, gene signatures from the prospective BIONNIK trial (presented at ESMO 2020) suggested that previously defined clusters may allow for personalized treatment. In this trial ccrcc2 pro-angiogenic tumors respond to TKI, ccrcc3 ‘normal-like’ tumors respond to TKI, ccrcc1 ‘immune-low’ tumors respond to the combination of nivolumab + ipilimumab, and ccrcc4 ‘immune-high’ tumors respond to nivolumab alone.

Somatic variant analysis represents ‘medicine that has not been on our radar yet’ according to Dr. Schmidinger. Patients with CDKN2A/loss and/or TP53 mutations may respond to stromal disrupters such as telmisartan and cytotoxic agents or CDK46 inhibitors such as palbociclib and ribociclib. Additionally, tumors with loss of function in ARID1A and KMT2C are implicated in epigenetic dysregulation and DNA repair deficiency, suggesting that it may be beneficial to combine epigenetic regulators with checkpoint inhibitors.

The microbiome may also be a major player in personalized medicine for metastatic RCC treatment given that multiple studies have shown a link between the intestinal microbiome and response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. For example, in the NIVOREN GETUG-AFU 26 trial, the ORR with antibiotics was 9% compared to 28% for patients without antibiotics, and a median PFS and OS that was significantly longer in the non-antibiotic group.

Dr. Schmidinger concluded her presentation with the following take-home messages:

- Easily available biomarkers (PD-L1, sarcomatoid features, NLR) are prognostic rather than predictive

- Tumor mutational burden, neoantigens, INDELS, genetic alterations have inclusive results, and are currently not able to guide therapy

- It is too early for the immune cell composition in the tumor microenvironment and circulating immune cells to guide therapy

- mRNA signatures have the highest potential to become relevant for treatment selection in the future and may identify candidates for single agent TKI (ie. ccrcc2, ccrcc3) single agent ICI (ie. ccrcc4, BIONIKK), and ICI doublets versus ICI/TKI combinations TeffhighMyeloidhigh gene signature/IMmotion 150/151, etc), but we need more data on patients treated by ICI only

- There is no data yet for selection of TKI within a ICI/TKI combination, but this is much needed given that TKIs may differ in their immune modulatory properties

- Recent data may encourage us to conduct studies with different agents that have not been on our radar yet: stromal disruptors such as telmisartan, cytotoxic agents or CDK46 inhibitors such as palbociclib and ribociclib, which arrest the tumor cycle and trigger antitumor immunity

- It may take time to incorporate these findings into clinical practice, but for now they have tremendously increased our understanding of this heterogeneous disease

Presented by: Manuela Schmidinger, MD, Department of Urology, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Urologic Oncologist, Assistant Professor of Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University/Medical College of Georgia, @zklaassen_md on Twitter during the 2021 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Annual Congress 2021, Thursday, Sep 16, 2021 – Tuesday, Sep 21, 2021.

References:

- Lalani AK, Xie W, Martini DJ, et al. Change in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in response to immune checkpoint blockade for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2018 Jan 22;6(1):5.

- Rini BI, Powles T, Atkins MB, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (IMmotion151): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2019 Jun 15;393(10189):2404-2415.

- Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;378(14):1277-1290.

- Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021 Mar 4;384(9):829-841.

- Iacovelli R, Ciccarese C, Bria E, et al. Patients with sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma – re-defining the first-line treatment: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2020 Sep;136:195-203.

- Bueselinck B, Job S, Becht E, et a. Molecular subtypes of clear cell renal cell carcinoma are associated with sunitinib response in the metastatic setting. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Mar 15;21(6):1329-1339.

- Motzer RJ, Robbins PB, Powles T, et al. Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in advanced renal cell carcinoma: Biomarker analysis of the phase 3 JAVELIN Renal 101 trial. Nat Med. 2020 Nov;26(11):1733-1741.