To this end, the Johns Hopkins Greenberg Bladder Cancer Institute and the American Urological Association held a Translational Research Collaboration entitled “Drug Development in NMIBC from Scientific, Regulatory, Clinician, and Patient Perspectives”. The second session of this symposium focused on Clinical Dilemmas in Management of NMIBC. In this session, Dr. Porten presented on the use of sequential therapy in patients with BCG unresponsive disease.

Before moving into her talk, she highlighted the definition of BCG unresponsive disease, emphasizing that patients who do not reach a disease-free state at 6 months following starting BCG with evidence of:

1. CIS or HG-Ta after two cycles of BCG (induction + maintenance or two inductions)

2. HG-T1 after induction BCG

or recurrence of high-grade disease within 12 months after achieving a disease-free state after adequate BCG.

Beginning her talk, she first presented the case of a 70-year old man with HG-Ta with recurrent HG-Ta and CIS following BCG induction x6 and 2 courses of maintenance therapy. His past medical history is notable for hypertension and diabetes. Imaging with CT urogram demonstrated no evidence of upper tract disease or lymphadenopathy.

In this situation, Dr. Porten emphasized that there are many treatment options, including cystectomy as guideline-concordant standard of care. Among other options, pembrolizumab and valrubicin are the only FDA-approved agents.

Considering individual patient counseling, Dr. Porten emphasized the importance of considering patient’s individual priorities including the importance of keeping their bladder, cancer control, treatment morbidity, and others. In the end, she emphasized that there are no tests to help guide care and thus we need to integrate clinical info and the patient’s goals of care.

When guiding these treatment decisions, Dr. Porten emphasized that not all BCG unresponsive states are equivalent, particularly emphasizing that patients with HG-T1 with CIS and HG-T1 have a non-zero rate of extravesical disease and lymph node spread. Depending on definitions and trials, rates of nodal involvement range from 1.5 to 15% with older series as high as 0%. She further emphasized that re-resection and imaging are necessary and variant histology may confer an unpredictable natural history. She emphasized that CIS in particular was associated with a relatively high rate of muscle-invasive disease and lymph node involvement.

Further, considering treatment options, not all BCG unresponsive treatment options are approved in all disease spaces (or have relevant data to guide decisions). For example, CIS only disease is heavily represented in trials assessing pembrolizumab and N-803 with low rates of papillary disease. Even among other trials that had broader inclusion, including those assessing nadofaragene, still had a preponderance of patients with CIS.

Further, not all patients with BCG unresponsive disease have the same window of opportunity for cure, which must be weighed against a patient’s desire to keep their bladder. She highlighted that patients with high-risk disease have a non-trivial mortality rate including 2.5% at 1.5 years. Further, OS worse than CSS given the comorbidity profile in this population. Given that most patients with HG-Ta and CIS have an approximately 5% annual rate of progression, she suggested that these patients may have up to 2 years allowing for attempts at multiple lines of therapy while those with HG-T1 disease have a higher risk of progression and thus suggested that cystectomy should be strongly considered following one line of bladder sparing therapy in the BCG unresponsive space.

Further, while we know that data in this space is populated with patients who are heavily pre-treated with BCG, available data on other treatments following BCG unresponsive disease is limited. For example, in recent data from Dr. Chamie at ASCO-GU, approximately one quarter of patients in the QUILT trial of N-803 had prior non-BCG intravesical therapies.

She emphasized that we must consider patient-centered factors, considering data on patient’s priorities. Citing survey data, Dr. Porten highlighted that the primary patient goal is bladder preservation followed Patient-centered factors – most want to keep their bladder then prevention of progression to MIBC.

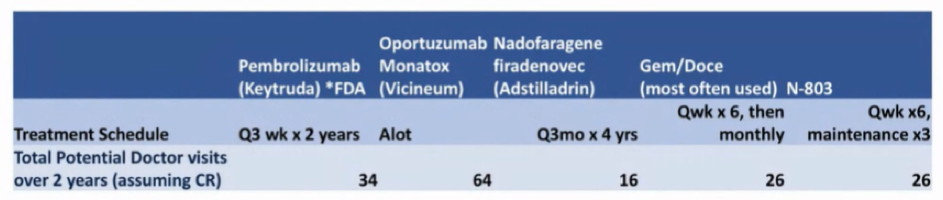

However, other factors matter too. To this end, Dr. Porten highlighted the importance of considering patients current symptoms such as bladder pain, lower urinary tract symptoms, quality of life impairment (including sleep and others), as well as anxiety and coping. While these are not absolute contraindications to any treatment approach, they are potentially reversible and should be discussed, mitigated, and potentially incorporated into treatment decisions. Additionally, given the importance of holding intra intravesical therapies prior to voiding, management of current symptomatology may be critical to allow for further lines of bladder sparing therapy. Finally, she highlighted other logistic considerations including travel time, the number of treatments and physician visits required, time off work, and cost.

She further emphasized that, despite promise and optimism, complete response rates and durability of treatment response need to be considered reasonable with the consideration that the vast majority of patients with progress and will need further therapy. She highlighted a recent systematic review from Dr. Kamat and colleagues which demonstrated 12 month response rates of 24% (95% CI 16-32%) among patients who had received two or more prior BCG courses before being treated for BCG unresponsive disease and 36% (95% CI 25-47%) for those who had received one or more prior courses.

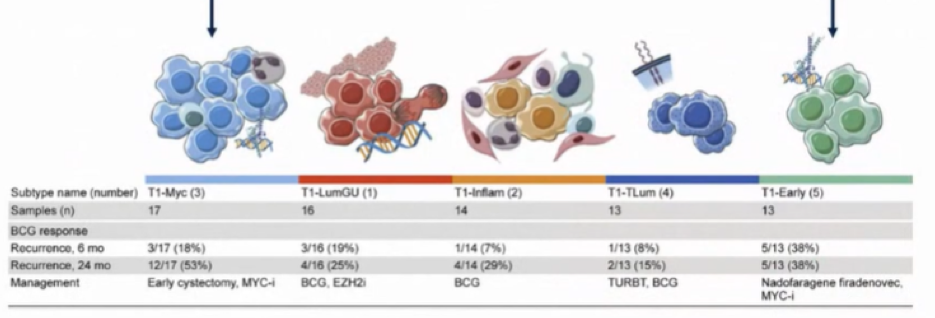

Given these results, as well as the proliferation of treatment options, she emphasized that we need biomarkers to guide treatment. Data from the Keynote-057 demonstrated that PD-L1 immunohistochemistry is inadequate. However, further work has shown that the genomic profile of BCG unresponsive disease is similar to that of tumors from the same patient prior to BCG treatment. Citing recent work from Dr. Kates and colleagues, she hypothesized that co-localization of PD-L1 and CD8+ T cells may predict treatment response. Further recent work has demonstrated subtypes of T1 bladder cancer with worse response to BCG and worse outcomes. However, how this data should be made actionable is uncertain – it is unclear whether we ought to attempt initial treatment with BCG followed by another approach or whether we ought to use initial intensified therapy.

Further ongoing work remains to identify biomarkers in this disease space. However, she highlighted a recent UroToday interview with Dr. Alex Wyatt in which he emphasized that whole post-BCG tumors are related to the initial pre-BCG tumors, there is variability and heterogeneity in the progression of these tumors from a clonal and evolutionary perspective.

Based on this premise, she then highlighted the concept of adaptive therapy, premised on the idea that we use evolutionary biology to manage a non-curative treatment with the goal of keeping disease progression at bay without ever eradicating disease. To employ this approach, she emphasized that we need multiple efficacious treatment options, we need a disease where cure is either not desirable or feasible as a result of the morbidity of attempting this, and we need a reasonable understanding of underlying biology. As highlighted in the figure below, an adaptive treatment approach can use intermittent treatment with an agent, allowing for sensitive cells to repopulate and compete against resistant cells with the goal of controlling cancer growth while retaining the tumor in a sensitive state. This can be accomplished with the use of multiple agents, either sequentially or concomitantly. From an evolutionary perspective, this approach seeks to use treatments to return the tumor to a composition similar to how it started treatment.

This approach is being tested in other oncologic disease states, including advanced prostate cancer in which use of androgen targeting agents and taxane chemotherapy may be combined in this adaptive approach.

Moving back to her initial case, this patient underwent pembrolizumab and had further disease progression. However, in the interval, he had stopped smoking and his urinary symptoms had improved. Given his ongoing interest in bladder preservation, they then attempted a trial of gemcitabine and docetaxel, while Dr. Porten did seek to prepare the patient for what a cystectomy would entail.

In conclusion, Dr. Porten emphasized that patients desire bladder preservation and for many there is time to attempt this without losing the window for cure. Given the lack of data and biomarkers to guide decisions, sequencing today should be guided by clinical acumen and patient priorities. However, looking forward, there is an urgent need for better prognostic information based on clinical data, for biomarkers to guide treatment selection, and for clinical trial design that reflects the clinical conundrum of treatment sequencing.

Presented by: Sima Porten, MD, MPH, Urologic cancer surgeon, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center