(UroToday.com) The 2024 PSMA conference featured a presentation by Dr. Oliver Sartor discussing the optimal timing of PSMA radioligand therapy. Dr. Sartor emphasized that the question of “When is the optimal time for any therapy?” is provocative, and may have several potential answers:

- When it is proven effective using criteria we have confidence in

- When it is proven superior to all the known alternatives (which never happens)

- When it is preferred over the known alternatives

Several criteria that we have confidence in for deeming effectiveness have been achieved in several radioligand therapy trials. With regards to overall survival, this was achieved in the VISION and TheraP trials.1,2 For both radiographic progression free survival and objective response rate, these outcomes were attained in the VISION and PSMAfore trials. Finally, a favorable adverse event profile was achieved in the VISION, PSMAfore, TheraP, and EnzaP trials. However, there are two caveats, which include (i) the control arms in VISION and PSMAfore were not optimized, and (ii) radiographic progression free survival in TheraP and EnzaP were deemed “controversial.”

Both the achievement of castration and receiving chemotherapy have significant side effects that can often make choosing therapies challenging. Castration is associated with loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, fatigue, cognitive issues, depression, emotional lability, muscle loss, bone loss, lassitude, hot flashes, glucose intolerance, etc. Chemotherapy is associated with fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hair loss, mouth sores, skin and nail problems, memory loss, nerve damage, increased risk of infection, etc. As such, Dr. Sartor proposed that radioligand therapy should be given before castration and before chemotherapy so that these side effects can be delayed and/or avoided.

As highlighted in the following figure, standard therapies are dominated by achieving castration and chemotherapy, both in the castrate sensitive and metastatic castrate resistant disease spaces:

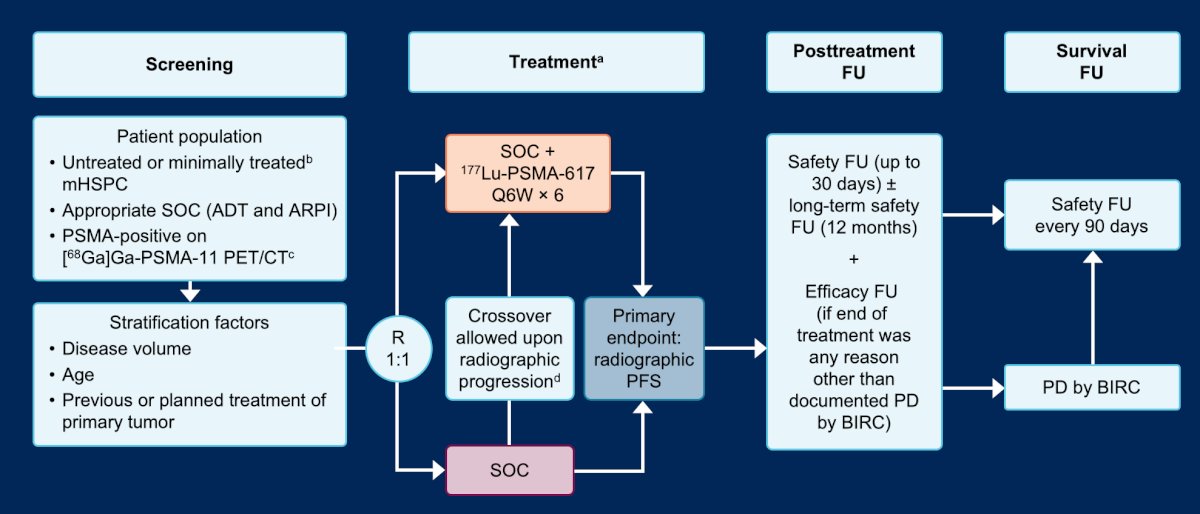

Focusing on castration-sensitive disease, Dr. Sartor discussed the PSMAddition study, which is randomizing untreated or minimally treated men with mHSPC with PSMA positive lesions on 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT to six cycles of 177Lu-PSMA-617 + standard of care versus standard of care alone. The primary endpoint for this trial is radiographic progression free survival:

To potentially challenge the castration paradigm, a study by Sathekge et al. recently published findings retrospectively assessing 21 mHSPC patients who refused standard treatment options (ADT ± docetaxel, abiraterone acetate, or enzalutamide) and were treated with 225Ac-PSMA-617 alone.3 Following treatment, 95% had any decline in PSA, and 86% of patients presented with a PSA decline of ≥ 50% including 4 patients in whom PSA became undetectable:

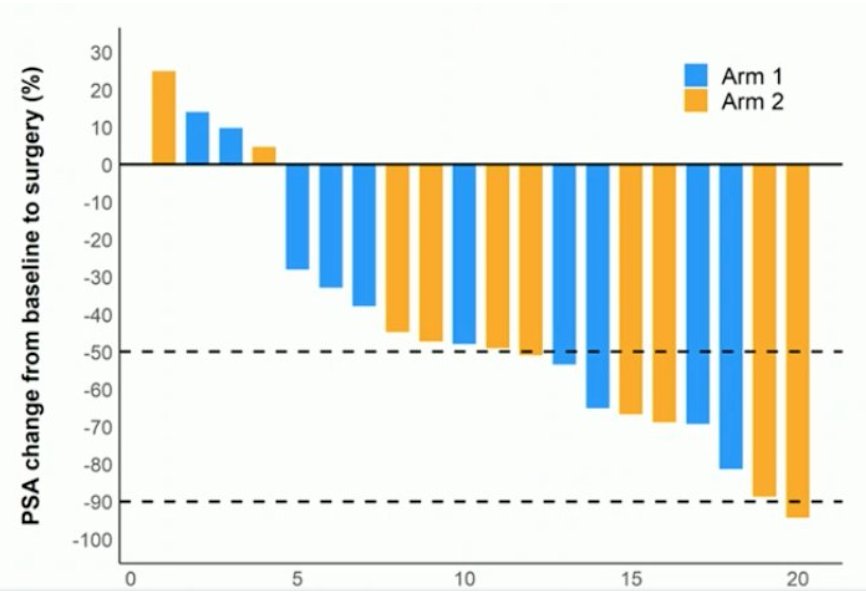

With regards to treating non-metastatic disease, Dr. Sartor discussed the LuTectomy trial, which is a single-center, single-arm, phase 1/2 study assessing the administration of [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 prior to radical prostatectomy in men with high-risk localized prostate cancer:4

This study included 20 patients, 10 in Cohort A (received one cycle of therapy) and 10 in Cohort B (received two cycles of therapy) followed by radical prostatectomy six weeks later. Overall, nine (45%) patients achieved >50% PSA decline, histopathological evidence of treatment effect was seen in 16 (80%) patients, one had minimal residual disease on final histology, and no patients achieved a complete pathological response. The PSA change from baseline to surgery is as follows:

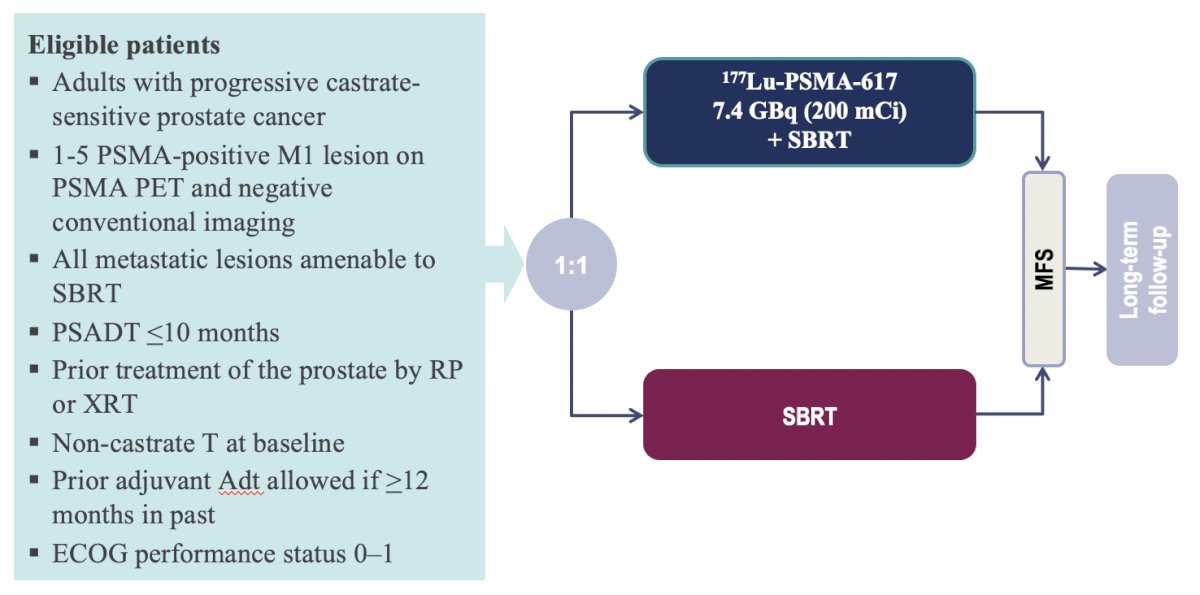

Dr. Sartor then discussed the potential of treating very early metastatic disease. For example, this may include patients with PSMA PET positive and conventional imaging negative disease. To answer this question, there is the ongoing PSMA-DC trial, which is a phase 3 open-label study comparing 177Lu-PSMA-617 versus observation in PSMA positive oligometastatic prostate cancer. Eligible patients are those with progressive castrate sensitive prostate cancer, 1-5 PSMA-positive M1 lesion on PSMA PET and negative conventional imaging, all metastatic lesions amenable to SBRT, and PSA doubling time <= 10 months. The primary endpoint is metastasis free survival by conventional imaging:

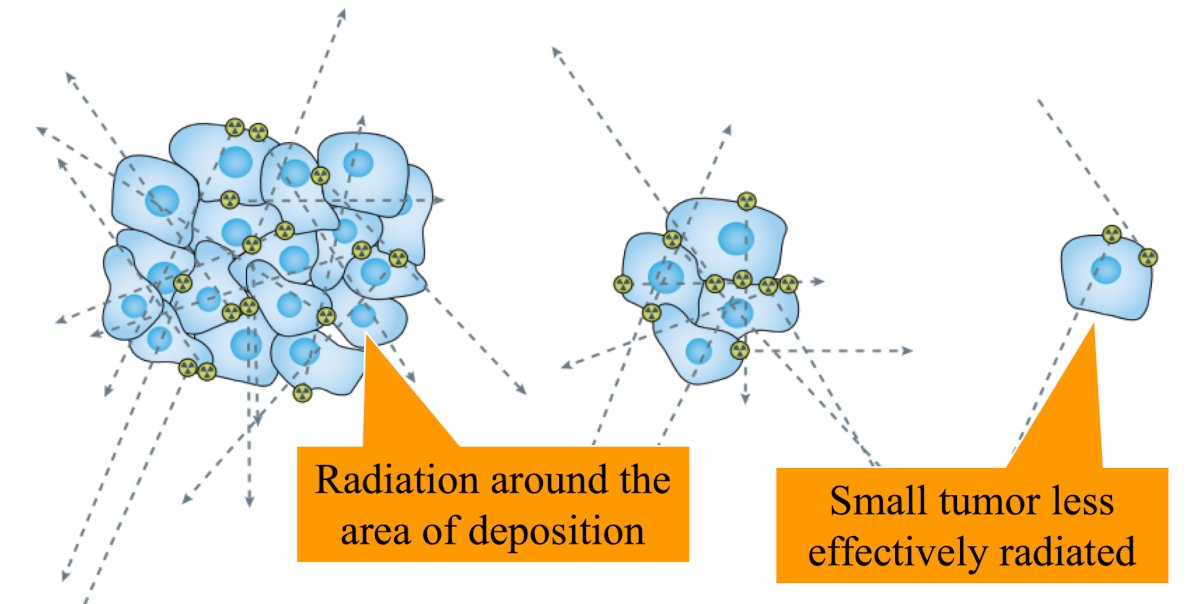

Dr. Sartor also emphasized that cross fire with beta particles likely helps to treat the entire tumor and the microenvironment:5

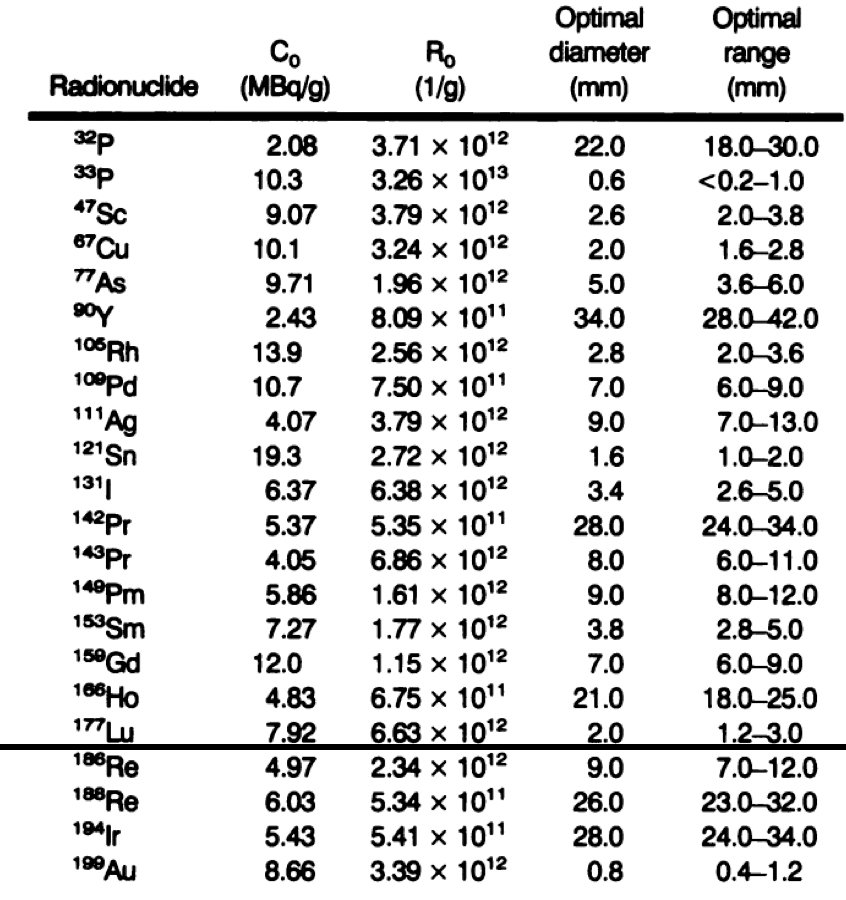

Additionally, with regards to beta particles having a chance when treating small tumors, work from 1995 from O’Donoghue et al. noted the following values of initial activity and number of bound radionuclide atoms per gram required to produce a cure probability of 0.9 at the optimal size:6

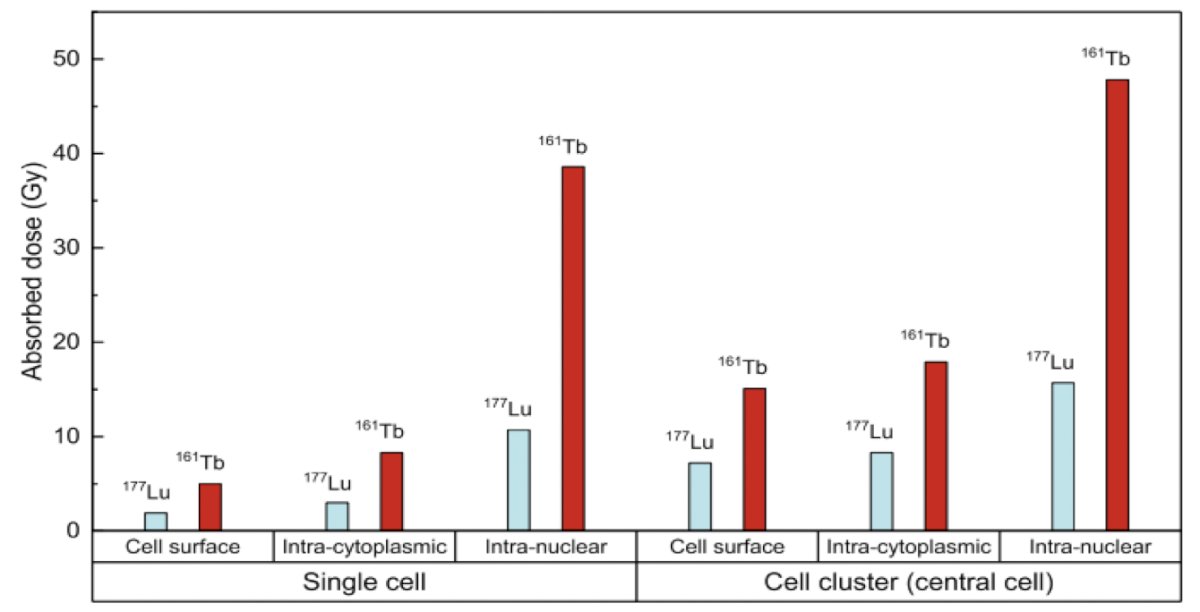

To assess the impact of therapy at the single tumor cell level, work from Alcocer-Avila and colleagues evaluated radiation doses from 161Tb (a medium-energy β- emitter with additional Auger and conversion electron emissions) and 177Lu in single tumor cells and micrometastases.7 They found that the dose to the nucleus was substantially higher with 161Tb compared to 177Lu, regardless of the radionuclide distribution:

- 5.0 Gy vs. 1.9 Gy in the case of cell surface distribution

- 8.3 Gy vs. 3.0 Gy for intracytoplasmic distribution

- 38.6 Gy vs. 10.7 Gy for intranuclear location

With the addition of the neighboring cells, the radiation doses increased, but remained consistently higher for 161Tb compared to 177Lu:

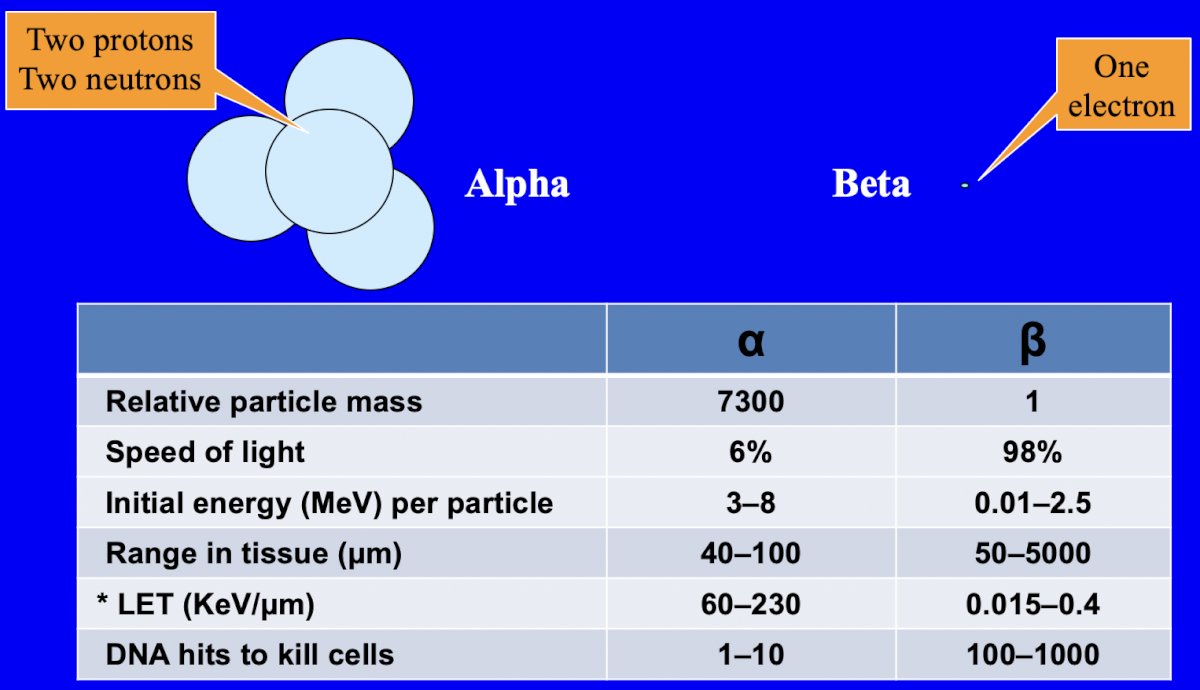

Ultimately, Dr. Sartor notes that alpha particles are likely better than any beta particles for low volume cancers:8

Dr. Sartor concluded his presentation discussing the optimal timing of PSMA radioligand therapy with the following take-home points:

- The optimal time is when you provide clinically meaningful improvements as compared to a standard of care

- The optimal time is also when you can get regulatory approval based on the tested endpoints, given that with no approval there is no appreciable gain

- The optimal time is when you can provide a reasonable alternative to the castration/chemotherapy paradigm that our patients abhor

Presented by: Oliver Sartor, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Urologic Oncologist, Associate Professor of Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Wellstar MCG Health, @zklaassen_md on Twitter during the 2024 PSMA Conference, San Francisco, CA, Thurs, Jan 18 – Fri, Jan 19, 2024.

Related content: What is the Optimal Time for PSMA Radioligand Therapy? "Presentation" - Oliver Sartor

References:

- Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 16;385(12):1091-1103.

- Hofman MS, Emmett L, Sandhu S, et al. [(177)Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): A randomized, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021 Feb 27;397(10276):797-804.

- Sathekge M, Bruchertseifer F, Vorster M, et al. 225Ac-PSMA-617 radioligand therapy of de novo metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate carcinoma (mHSPC): Preliminary clinical findings. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023 Jun;50(7):2210-2218.

- Eapen RS, Buteau JP, Jackson P, et al. Administering [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 Prior to Radical Prostatectomy in Men with High-risk Localized Prostate Cancer (LuTectomy): A Single-centre, single-arm, phase 1/2 study. Eur Urol. 2023 Oct 25:S0302-2838(23)03087-7.

- Sgouros G, Bodei L, McDevitt MR, et al. Radiopharmaceutical therapy in cancer: Clinical advances and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020 Sep;19(9):589-608.

- O’Donoghue JA, Bardies M, Wheldon TE. Relationships between tumor size and curability for uniformly targeted therapy with beta-emitting radionuclides. J Nucl Med. 1995 Oct;36(10):1902-1909.

- Alcocer-Avila ME, Ferreira A, Quinto MA, et al. Radiation doses from 161Tb and 177Lu in single tumour cells and micrometastases. EJNMMI Phys. 2020 May 19;7(1):33.

- Henriksen G, Fisher DR, Roeske JC, et al. Targeting of osseous sites with alpha-emitting 223Ra: Comparison with the beta-emitter 89Sr in mice. J Nucl Med. 2003 Feb;44(2):252-259.