(UroToday.com) In the Bedford Waters Lecture at this year’s Southeast Section of the American Urologic Association Virtual Annual Meeting, Dr. Litwin presented on the Critical Pursuit of Social Justice in Urology.

After recognition of the profound contributions of Dr. Bedford Waters to the field of urology, Dr. Litwin began his talk by highlighting the well-known quote from Dr. Martin Luther King who said, “Injustice anywhere threatens justice everywhere”. While less well know, Dr. Litwin then emphasized the second, less-known, half of this quote to say, “Injustice anywhere threatens justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Highlighting but a few examples of health inequality in urology in which patients receive sub-standard care or experience poorer outcome as a result of their race, ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status, or other characteristics, Dr. Litwin stressed that there are hundreds and hundreds of papers in the literature assessing and demonstrating health inequalities in urology.

He then emphasized that, over the past year, outcomes for COVID-19 demonstrate profound inequalities: for example, while the case numbers are similar between White, Non-Hispanics and Black or African Americans, death rates and hospitalizations are more than 2x and 3x higher, respectively. Further, case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths are higher among American Indian and Hispanic/Latino populations.

Dr. Litwin then described the tremendous library of health disparities research. In general, this work comes in three phases: first, describing relevant inequities; second, synthesizing evidence and identifying targets for intervention; and third, implementing and studying interventions to bridge gaps. Of these, the third is the most critical. Unfortunately, it is also the least common.

Just as there is a conceptual framework from translational basic science work to clinical practice, there is such a model for health services work addressing health inequalities. This relies on the three phases highlighted above. Notably, given the scope of the issues addressed, this work must both begin and eventually return to the community.

Dr. Litwin then delved into the causes underlying these health disparities, premised largely on social determinants of health. These social and structural determinants of health include economic stability, neighborhood and physical environment, education, food, community, and social context, and the health care system (which he emphasized is, in the United States, really a series of poorly integrated health care systems). Underpinning differences in these social and structural determinants of health are structural discrimination and racism.

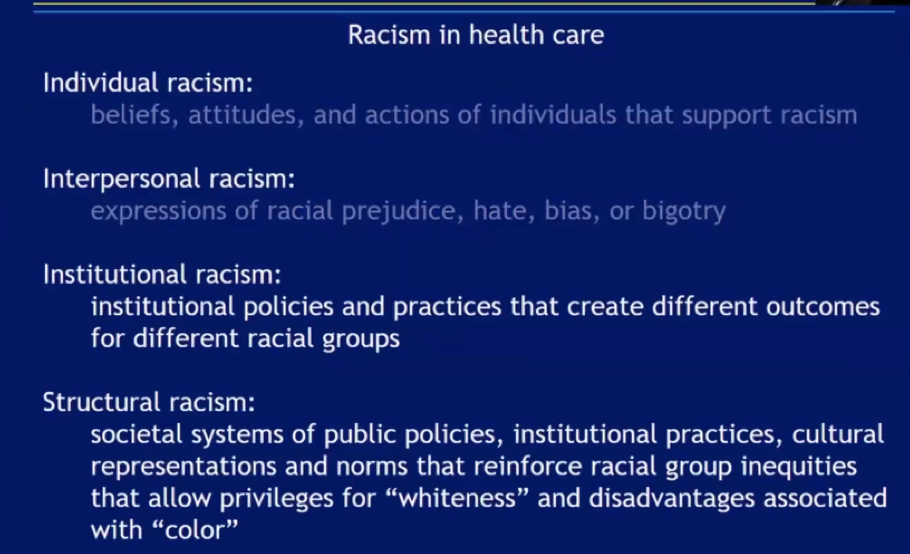

Thus, Dr. Litwin then focused on racism in health care. He emphasized that racism can run from individual, internal racism through to structural racism. At the personal level, individual racism encompasses the beliefs, attitudes, and actions of individuals that support racism while interpersonal racism is the expressions of racial prejudice, hate, bias, and bigotry between individuals. While these are clearly harmful, even more, problematic are institutional and structural racism. While these are often not intentional, Dr. Litwin emphasized that if actions (whether at the personal, institutional, or structural level) create different outcomes for different racial groups, then this is racism.

He then cited a number of examples of ingrained structural racism and discrimination in American society. He first gave the example of redlining in which the Federal Housing Authority and financial institutions systematically denied financial services (including mortgages necessary for house purchase) on the basis of an individual’s location in a manner that predominately affected Black, Mexican American, Asian American, and other immigrant communities. The inability to purchase housing severely curtailed intergenerational wealth transfer in a manner that still affects socioeconomics and health outcomes decades later. Further, racial segregation and lack of opportunities, in a cascade, affect health outcomes and health access both directly and indirectly through disinvestment in business, less economic opportunity, poorer housing conditions, poorer education, fewer funds for community development, and an increasing wealth gap.

Dr. Litwin highlighted, using a recently published manuscript from Circulation, how the circumstances of the very founding of the United States, based in racism and slavery, continue to be directly relevant to current health care delivery and outcomes.

Pivoting somewhat, Dr. Litwin asked the audience to consider the concept of privilege, defining it as something you have that benefits you that you didn’t work for. He then took the audience through a self-test of privilege, as highlighted in the figure below:

Visualized somewhat differently, the privilege may be conceptualized as a wheel – individuals will have varying degrees of privilege on the basis of a number of characteristics, including gender, citizenship, skin color, education, ability, sexuality, and many others. The closer one lies to the center of the wheel, the greater their privilege.

While it may be uncomfortable for many, the first key to contributing meaningfully is to acknowledge our own privilege and use it to help those with less privilege.

While health care may lag behind, Dr. Litwin emphasized that the value of diversity has been recognized in corporate American, with proven benefits as a driver of innovation and a critical component of success on a global scale. Further, a diverse and inclusive workforce is critical to attract and retain talent. Citing evidence Evan Apfelbaum from the Boston University Business School, Dr. Litwin emphasized that diversity causes friction which “makes us work harder”. This friction can, in Apfelbaum’s words, “become the irritant that creates the pearl, in terms of an idea, or correcting a mistaken assumption”. However, this process can be uncomfortable.

Further, Dr. Litwin emphasized that evidence, from the business world, that the best teams, that obtain the best outcomes, do not necessarily have the best individuals. Rather, it is the synergistic output of a diverse group that can yield the greatest outcomes.

Taking this concept to the question of health care delivery, Dr. Litwin emphasized the clear link between the urology workforce, healthcare delivery, and urology patient outcomes. Thus, building on the prior concept, diversity in the urologic workforce is critical to achieving the best outcomes for patients with urologic conditions. For many years, and until this day, many racial and ethnic groups have been dramatically underrepresented in medicine and in urology.

This is particularly true in the more senior aspects of our specialty.

As it relates to identifying and encouraging diversity and representation in Urology, Dr. Litwin highlighted many hurdles we face. First, among these, only eight of the 16 United States mainland medical schools with the highest representation of underrepresented minorities have a Urology Department.

Further, for a specialty such as Urology which typically has competitive applications and entry, there are important contributions of achievement which may create barriers. As highlighted by Teherani (2018), a combination of student-level personal and interpersonal factors, faculty/resident rater factors, cultural and structural factors of the clinical learning environment, and school policies and procedures may contribute to lower apparent performance in under-represented in medicine students which may, in turn, contribute to fewer career opportunities.

In a recent publication in JAMA, Dr. Ellis highlighted that the interview experiences of Black applicants differ on account of verbal and non-verbal microaggressions, stereotypic threats, tokenism, imposter syndrome, and homophily.

Considering how we may move forward, Dr. Litwin highlighted the difference between equality, in which all are treated equally though with potentially disparate outcomes and equity in which resource is allocated on the basis of need to ensure equitable outcomes.

To make progress, Dr. Litwin highlighted that we must first start with ourselves. In adding to acknowledging our privilege as discussed previously, he emphasized the importance of considering our implicit biases. This is particularly relevant among physicians as previous work has shown a correlation between educational achievement and implicit bias.

Dr. Litwin encouraged all to test their own implicit bias, including by using the Harvard Implicit Bias Check (implicit.harvard.edu/implicit). Circling back to a point made previously, he highlighted the importance of acknowledging our own privilege, where we have it, and using it to help others – through allyship, sponsorship, mentoring, and bystander training.

Across corporate America, and in many health care systems, there is now action fomenting to address issues of health disparities. He highlighted a few examples from the Wake Forest Baptist Health System and the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine. Utilizing the example of the University of California, he emphasized the importance of beginning with transparency: the race, ethnicity, gender, age, and many other characteristics of the UC academic workforce are publicly available. Within the UCLA Department of Medicine, an Anti-Racism Task Force was convened over the past year. While there are multiple working groups, including Awareness & Understanding, Representation, Equity in Care Delivery, Education & Training, he focused on work done by the Pipeline group. This working group focuses on outreach, including a partnership with Building Bridges, Saturday science academies, and a mentoring program in order to engage with lower socio-economic groups. Dr. Litwin emphasized that Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion form a core foundation of the department. Further, he highlighted that diversity begets diversity.

As his talk came to a close, Dr. Litwin again invoked the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, emphasizing that “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends”. He stressed that it is not an option to comfortably retreat from these issues, instead, we must step out into the world, confront its conflicts and make it a better place. He left us with the closing words of Dr. Okanlami, “The past may not be our fault, but the future will be”.

Presented by: Mark Litwin, MD, Chair of the Department of Urology at UCLA Health

Written by: Christopher J.D. Wallis, Urologic Oncology Fellow, Vanderbilt University Medical Center during the 85th Annual Southeastern Section of the American Urological Association, April 23-24, 2021