Beginning, Dr. Bagli gave an overview of relevant definitions, emphasizing that virtual care remains real medical care where the patient encounter is dependent on a communication/connecting technology with the physician and patient in different physical locations. Wearables can augment virtual care but do not define it.

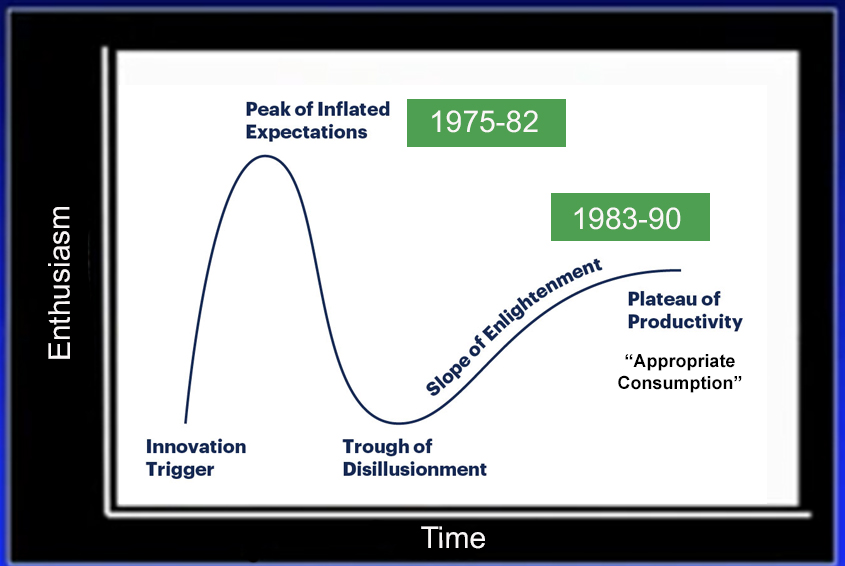

There is a long history of distance communication data dating back centuries with medical utilization of early communication technologies. Dr. Bagli highlighted a “radio doctor” report from 1924, however, the first reference to telemedicine in the medical literature appeared in 1950 and then quickly became more widespread. Through the 1950s and 1960s, ongoing innovation was targeted at improving access to health services for remote populations. In 1967, there was the first urban utilization of voice radio channels to transmit medical information and in the coming decades, teleradiology became more widespread. Dr. Bagli highlighted that excitement about these approaches peaked between 1975 and 1982 followed by a decline consistent with the so-called Gartner Hype Curve.

Subsequently, COVID-19 has driven increased utilization.

Examining drivers of virtual care, Dr. Bagli highlighted that this is more than eliminating distance (rural outreach bringing expertise non-physically), but rather speed, affordability, convenience, and value from the patient perspective, with the benefit of reducing carbon footprints as well. This is relevant is both rural and urban settings, independent of proximity to hospitals. Further, an electronic interaction offers added data potential including image, audio, video, and telemetry data which may be utilized to increase healthcare value.

Currently, the spectrum of virtual care spans a wide breadth of health care utilization, up to and including virtual intensive care unit (ICU) level care. Additionally, telerobotic surgery may be accomplished using commercially available network technology.

Artificial intelligence may be useful in many aspects of virtual care in which image interpretation is utilized including radiology and pathology and may be facilitated by virtual care models.

Interestingly, some research Dr. Bagli cited suggests a link between hospital performance and the adoption of telehealth including positive correlations between telehealth adoption and risk-adjusted mortality and complications.

In rolling out virtual care at the Hospital for Sick Children, Dr. Bagli highlighted the cornerstones of committing to equity of access, considering the use of virtual care first while ensuring appropriateness, protecting of personal information, striving for frictionless user experience, and optimizing value for all.

In deciding the context for a given clinical interaction, Dr. Bagli highlighted the importance of assessing the need for clinical physical examination, and the role of visual human interaction including the physician seeing the patient, the patient seeing the physician, and the value of human physical contact.

Dr. Bagli closed by highlighting that virtualizing care delivery will re-shape the practice of medicine. The driving force should be to add or increase value and we can consider the varying roles of audio, visual, and tactile interaction.

Presented by: Darius Bägli, MDCM, FRCSC, FAAP, FACS, Associate Head of Urology, Associate Surgeon-in-Chief, Department of Surgery, The Hospital for Sick Children, Professor of Surgery & Physiology, Senior Attending Urologist, Associate Head, Division of Urology, Senior Associate Scientist, Research Institute, The University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Written by: Christopher J.D. Wallis, MD, PhD, Urologic Oncology Fellow, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, Twitter: @WallisCJD at the 2020 Société Internationale d'Urologie Virtual Congress (#SIU2020), October 10th - October 11th, 2020