(UroToday.com) The 23rd Annual Meeting of the Society of Urologic Oncology held in San Diego, CA was host to a State of the Art Lecture addressing inequities in cancer screening, treatment, and outcomes presented by Dr. Mark S. Litwin.

Prior to presenting any data highlighting the known inequities in cancer screening, treatment, and outcomes, Dr. Litwin began his presentation with the following important quote from Dr. Hiss at the NIH in 2004: “In health research, ‘translation’ is the process through which breakthroughs in science are used to improve human health.”

Before we get into discussing the reasons and evidence for inequity in medicine, we need to define population science. Population science encompasses the following domains:

- Health services research

- Access, cost, quality

- Structure, process, outcomes

- Epidemiology and prevention

- Evidence-based practice

- Comparative effectiveness

- Technology diffusion

- Health equity and disparities

- Implementation science

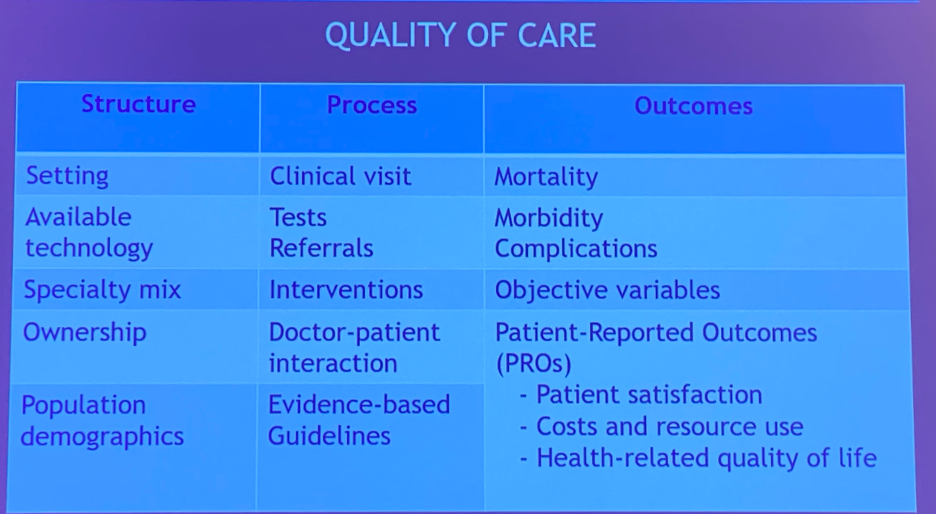

After defining population science, which notably does not include basic, translational, or clinical sciences, we need to discuss the components of quality of care that we provide. Only by understanding the elements of quality of care can we understand the root cause of cancer inequity. In the table below, Dr. Litwin highlighted the following components pertaining to the structure, process, and outcomes of quality of care.

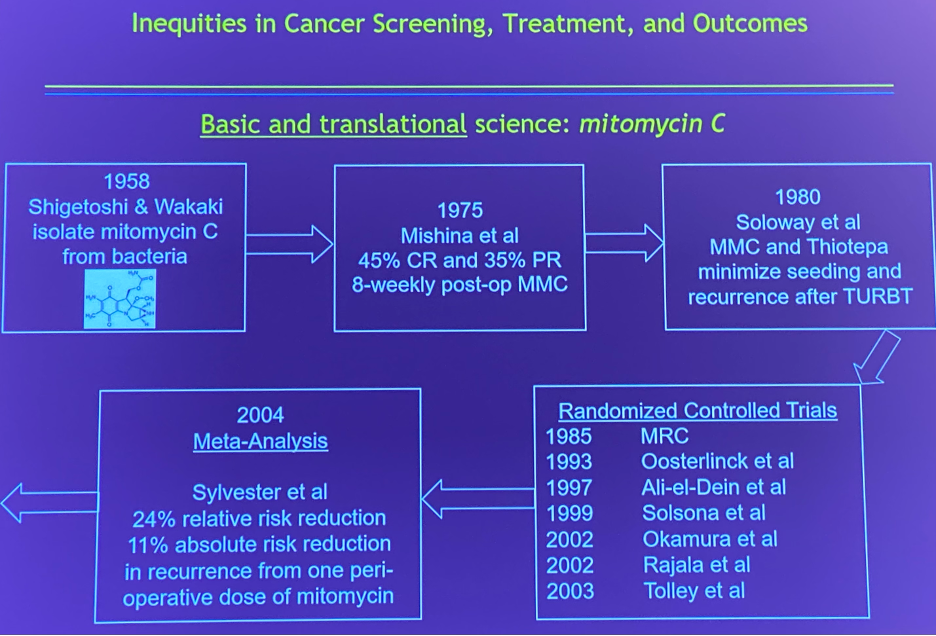

An important, often ignored, component of population science is the domain of implementation science. There is a strong emphasis on research that proves the efficacy/effectiveness/safety of interventions, but much less so on measures that facilitate implementation of these interventions in practice A great case study to highlight this deficiency is the use of a single dose of mitomycin C post-TURBT. Starting with the isolation of mitomycin C from bacteria in 1958 to the demonstration of mitomycin efficacy in an 8-weekly post-operative course to the publication of multiple clinical trials and a meta-analysis between 1985 and 2004, there have been significant efforts over five decades to demonstrate the efficacy of this intravesical drug in this disease space.

However, as demonstrated by Dr. Chamie during his fellowship at UCLA, the implementation of this intervention in practice has been poor. In 2009, Madeb et al. demonstrated that the utilization of mitomycin C in patients with high-grade Ta, Tis, and T1 bladder cancer was 0.3% only and a subsequent report by Chamie et al. in 2011 reported a modestly improved rate of 3.2%. A subsequent report by Chamie et al. in 2012 demonstrated that the overall adherence to guideline-recommended strategies overall in patients with high-grade Ta, Tis, and T1 bladder cancer was as low as 0.4%.1 It thus becomes clear that we need to place a larger emphasis on the “translation” of positive clinical interventions into practice. Only by improving this implementation of interventions can we even start to think about addressing the “elephant in the room”: inequities in cancer screening, treatment, and outcomes.

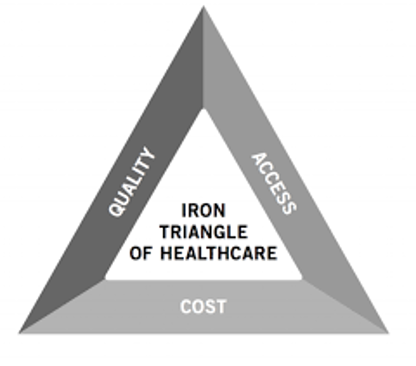

Published in JAMA Forum in 2012,2 Carroll et al. proposed the framework of the iron triangle of health care:

- Cost

- Access

- Quality

“You can’t change one or two without changing the third”.

This iron triangle is at the crux of the inequity problem that we face in practice. Multiple studies in the urology field have accordingly highlighted severe racial disparities in urologic oncology patients. In work published by Slopnick et al. in 2016,3 it was shown that Hispanic men were more likely to present with high-risk disease (OR 1.6; 95% CI: 1.2 to 2.0) and less likely to undergo a total penectomy (OR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.2 to 1.8). Furthermore, African American men were less likely to undergo surgery of any type (OR 0.7, 95% CI: 0.5 to 0.9) and had higher mortality compared to Caucasian men (OR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.1 to 1.4).

In 2022, Lillard, Moses et al. published a compelling review of racial disparities in black men with prostate cancer.4 In this review, they highlighted peer-reviewed studies that demonstrated that African American men were:

- Less likely to undergo screening

- More likely to present with higher stage and grade

- Less likely to undergo definitive treatment

- Less likely to undergo node dissection at the time of radical prostatectomy

- Had higher cancer mortality

- Concerningly, it appears that the gap is widening on longitudinal analyses

It is important to note that work from the Veterans Affairs SEARCH database, a reportedly “equal access” system, has demonstrated that many of these inequities disappear when patients are treated within the context of this health system. While this may be true, Dr. Litwin was quick to note that this was more of an “equal financial access” system than a truly “equal access” system.

These inequities are not restricted to racial differences. Further work in the bladder cancer disease space by Dobruch et al published in 2016 demonstrated that women were:

- Less likely to receive a timely urology referral for hematuria

- Less likely to receive complete evaluation for hematuria

- More likely to present with more advanced disease

- Have higher mortality

- Less likely to receive guideline-concordant care

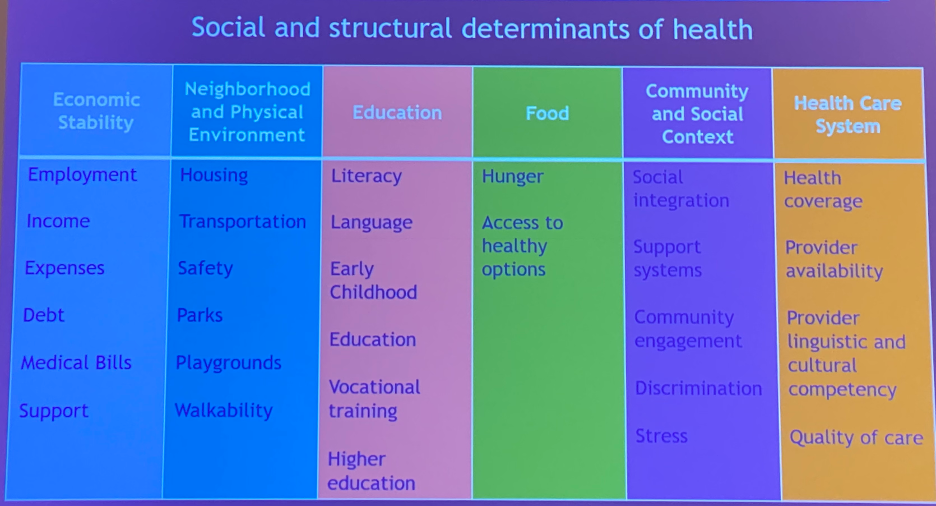

Future efforts to reduce disparities must focus on socioeconomic class, gender, race/ethnicity, and access to care. In order to address these disparities, we must focus on their etiology: why do disparities emerge? In order to better understand this, we need to evaluate the social and structural determinants of health:

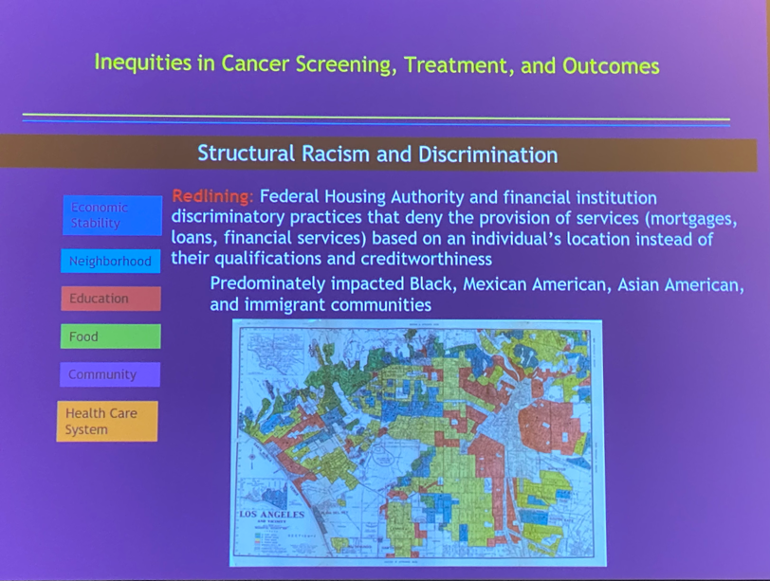

Dr. Litwin emphasized that these social and structural components are the root of “structural racism and discrimination”. Racism in health care can be attributed to:

- Individual racism: pertaining to beliefs, attitudes, and actions of individuals that support racism

- Interpersonal racism: Expressions of racial prejudice, hate, bias, and/or bigotry

- Institutional racism: Institutional policies and practices that create different outcomes for different racial groups

- Structural racism: Societal systems of public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and norms that reinforce racial group inequities that allow privileges for “whiteness” and disadvantages associated with “color”. An example of this is the housing policies previously explicitly applied by banking systems in California. These policies have led to racial segregation and lack of opportunities by disinvesting into businesses, providing less economic opportunities, poor housing conditions, poor education, less funds for community development, all leading to widening wealth gaps and poorer health care and access.

In addition to the socioeconomic implications of these inequities, there are physiologic implications to these disparities, as demonstrated in this cardiovascular disease development model:

But what are the current systemic challenges pertaining to systemic racism?

- Disease characteristics

- Awareness and knowledge in minority communities

- Cultural mistrust of the health care system

- Effective communication

- Health care access

- Geographic differences

- Economic differences

- Enrollment in clinical trials

In 2008, Fleming et al. proposed a conceptual framework for future health inequity research:

- Detect inequities (disparities)

- Majority of the work has been in this domain

- Assess causes and develop interventions

- Implement interventions and monitor impact

Conceptually, Fleming et al propose that these projects/initiative must start from the community, proceed to the bench, then to the bedside, and most importantly, back to the community.

Dr. Litwin’s group, led by Dr Sanchez, a current urology resident at UCLA, proposed the following policy-relevant conclusions:5

- Increase funding for programs that integrate social services and health care

- Standardize registry variables including self-reported race data, comorbidity data, insurance status, level of education, employment status, type of health care system within which patients are treated, and quality indicators

- Fund public health focused health care-community based collaboratives aimed to specifically address disparities through multidisciplinary efforts

- Increase funding for patient-centered technology-based programs in underserved settings

- Incentivize providers for working in underserved settings with higher incentives for those adhering to evidence-based practice

- Incentivize basic science research in urologic disease that focuses on the generic underpinnings of different genetic ancestry groups

- Require minimum minority and female accrual in clinical trials

- Academic research institutions should diversify their workforce and support pipeline programs for historically excluded or under-represented groups

- Increase funding and training programs for T3-T4 research

- Support implementation science research aimed at improving value-based payment models to incorporate equity and deconstruct health coverage/health system-level barriers

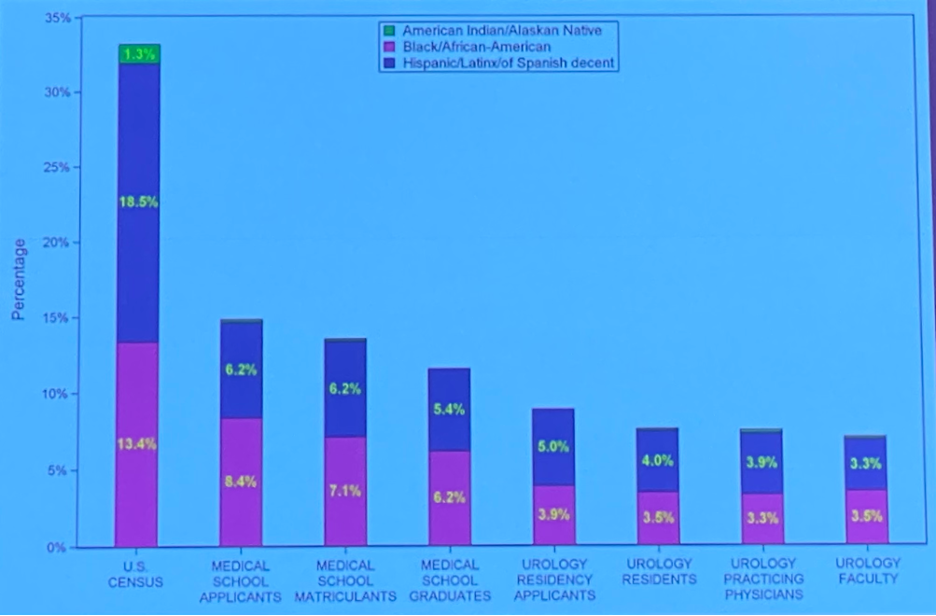

Another important issue highlighted by the UCLA group is the sequential, relative decrease in the percentage of US minorities occupying various positions within the medical system. As Americans progress from medical school applicants to graduates, all the way to urology residents and faculty, the relative proportion of African American, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaskan Native members progressively decreases, as demonstrated below:

Just as he started, Dr. Litwin concluded his talk with the following historic quote from Dr. Oluwaferanmi Okanlami: “The past may not be our fault, but the future will be.”

Presented by: Mark S. Litwin, MD, Professor and Chair of the Department of Urology, University of California in Los Angeles, CA

Written by: Rashid Sayyid, MD, MSc – Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Clinical Fellow at The University of Toronto, @rksayyid on Twitter during the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO), Nov 30 – Dec 2, 2022. San Diego, CA

References:

- Chamie K, et al. Quality of care in patients with bladder cancer: a case report? Cancer 2012;118(5):1412-21

- Carroll, A. The “Iron Triangle” of Health Care: Access, Cost, and Quality. JAMA Forum. 2012

- Slopnick EA, et al. Racial Disparities Differ for African Americans and Hispanics in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Penile Cancer. Urology. 2016;96:22-8.

- Lillard Jr JW, et al. Racial disparities in Black men with prostate cancer: A literature review. Cancer 2022;128(21):3787-95.

- Sanchez DE, et al. Moving urologic disparities research from evidence synthesis to translational research: a dynamic, multidisciplinary approach to tackling inequalities in urology. Urology 2022;162:49-56.