(UroToday.com) The 2023 Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) annual meeting held in Washington, D.C. between November 28th and December 1st, 2023, was host to a prostate cancer course. Dr. Simpa Salami discussed contemporary approaches to the active surveillance of prostate cancer patients using the ‘5 Ws and 1 H’ framework:

- What?

- Why?

- Who?

- When?

- How?

- Where?

Active surveillance is the multimodal monitoring of patients with low- or favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer with the goal of minimizing over-treatment and side effects of definitive therapy while transitioning to active treatment at the time of disease progression.

Why perform active surveillance? In essence, this approach aims to balance the benefits and harms of treatment, by identifying patients with aggressive cancers early in their disease course and offering them radical therapy that may confer a survival benefit. It also concurrently offers the opportunity to avoid ‘over-treatment’ of indolent cancers that are unlikely to cause prostate cancer-related mortality, thus avoiding the harms and side effects of radical therapy.

Who are the candidates for active surveillance? Patients with:

- Low-risk prostate cancer (Grade Group 1)

- Favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer

- Grade Group 2 disease

- Pattern 4 disease <20% and no cribriform features

- Grade Group 2 disease

- Percentage of positive biopsy cores <50%

- Fusion biopsy cores from a region of interest represents one core

- ≤1 NCCN intermediate risk factor

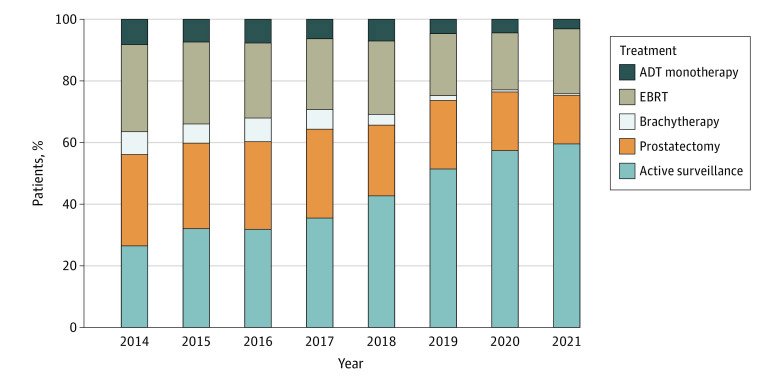

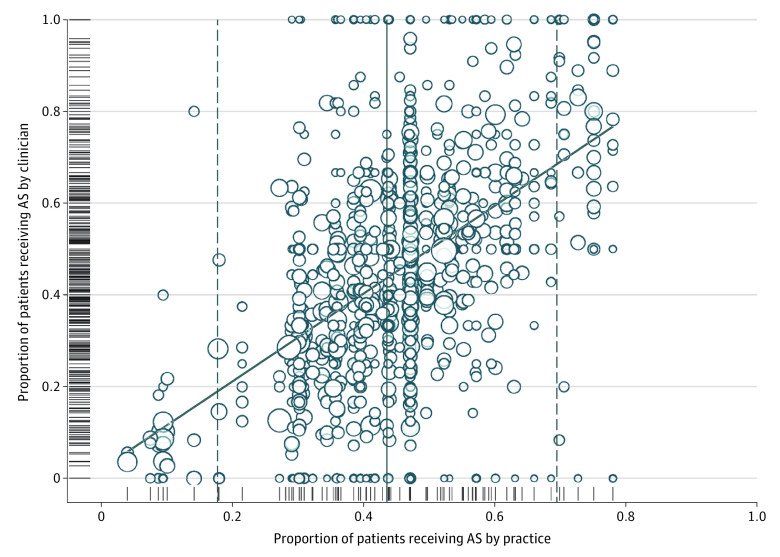

While this approach is currently recommended/endorsed by the AUA, ASCO, and SUO, the clinical implementation of this approach in practice remains less than ideal. In a recently published report from the AUA Quality (AQUA) Registry, Cooperberg et al. noted that the uptake of active surveillance in eligible candidates has increased from 27% in 2014 to 59% in 2021. While this represents a significant improvement, this still indicates that approximately 40% of US patients inappropriately receive active treatment for their indolent disease.

Significantly, the utilization of active surveillance ranged between 0% and 100% among providers, highlighting that many factors, including potential reimbursement incentives, continuing medical education (CME) disparities, and practice location may strongly influence management patterns.1

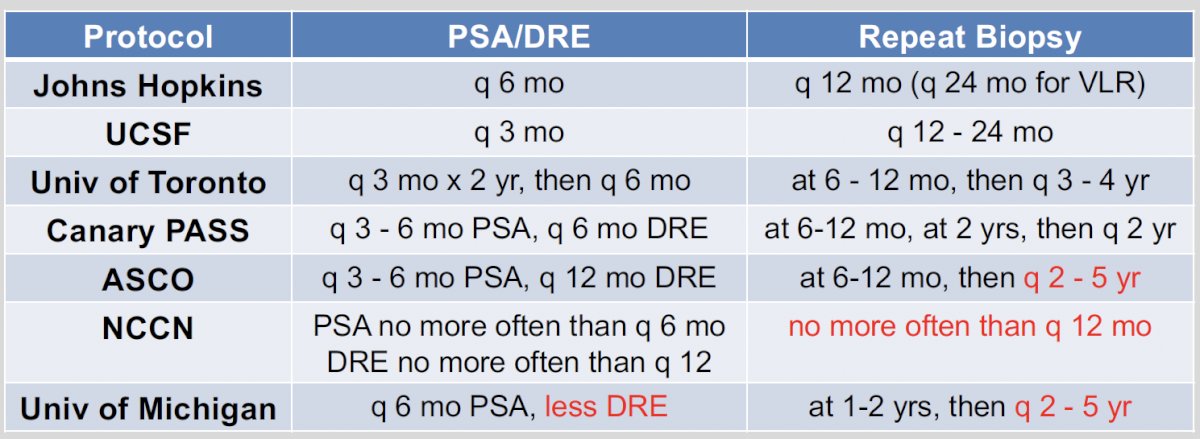

When to perform a PSA, digital rectal examination, and repeat biopsies as part of the active surveillance regimen? There are slight variations among the different active surveillance series, as summarized in the table below. Overall, a PSA is recommended every three to six months, with a DRE performed every six to 12 months. With regards to repeat biopsies, this heavily depends on whether the initial biopsy was performed under MR-guidance versus systematic. Generally, a repeat (i.e., confirmatory) biopsy is recommended within 12 months of diagnosis and can then be repeated as clinically indicated.

What are the outcomes of active surveillance patients in the prospective series? Progression-free survival, variably defined using volume, PSA, and grade criteria, varies between 40% and 76% at 5 years. Longer term data are sparse, but 10-year data from the Johns Hopkins and Sunnybrook (University of Toronto) series suggest that progression-free survival ranges between 51% and 64%. One of the major limitations of these series is the underutilization of MRI guidance to select patients for biopsy and guide biopsy approaches, which may limit the external generalizability of these results to contemporary practice. Nevertheless, a higher PSA density (i.e., serum PSA level/prostate volume) was consistently predictive of higher rates of disease progression, and patients with large volume of disease (i.e., higher number of positive cores involved) were also more likely to progress. Dr. Salami did also note that many of these patients who ‘progressed’ were treated for volume progression, which nowadays is less likely given the pre-biopsy performance of MRI that decreases the odds of ‘understaging’ such patients.

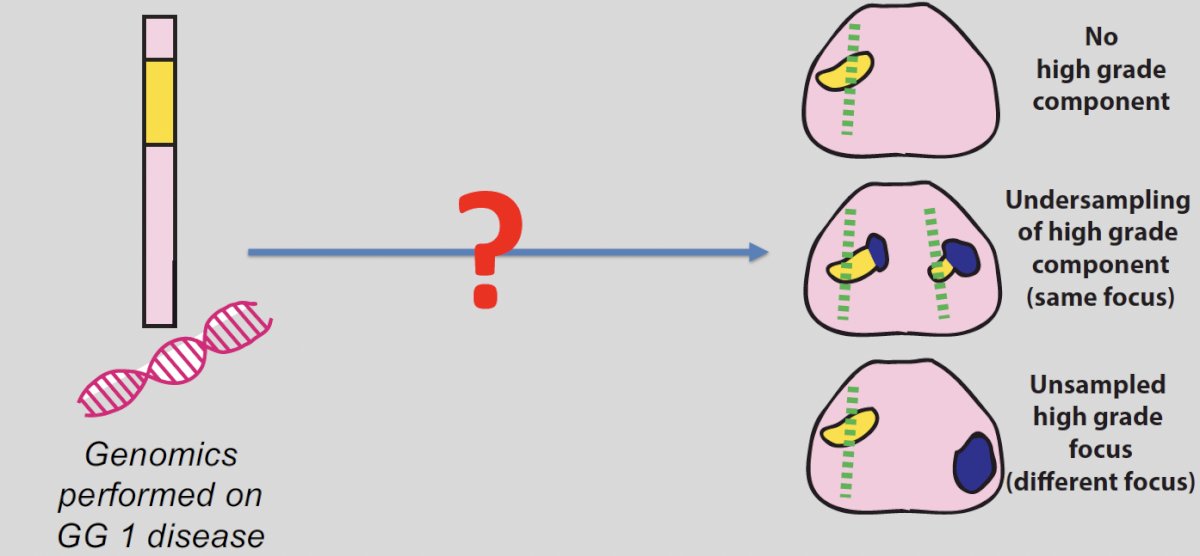

One the major goals of surveillance strategies is to detect disease progression. While this may be secondary to de novo higher grade disease development or clonal grade progression, this phenomenon is more often due to undersampled or even unsampled disease.

How to perform active surveillance (i.e., what are the tools available)? Currently available tools include:

- PSA and PSA density (PSA density >0.15 ng/ml/cc is associated with increased risk of disease progression)

- Prostate biopsies

- Multiparametric MRI

- Biomarkers (urinary, serum, and/or tissue)

- Evolving tools: nomograms and artificial intelligence

Prostate biopsies are not only helpful for detecting disease grade and volume progression but may also provide prognostic information, particularly when negative during surveillance. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nine studies (n=2,628) demonstrated that ‘negative’ surveillance biopsies occur in 20 to 30% of patients. The occurrence of such negative surveillance biopsies is associated with a 50% decreased risk of future disease re-classification/upgrading. Importantly, there were no differences irrespective of whether the negative biopsies occurred at the initial confirmatory biopsy or during later surveillance biopsies and whether patients had Grade Group one or two disease at diagnosis.2

One of the issues of MRI for active surveillance is the significant interobserver variability (kappa= 0.15 – 0.61). There are also several limitations to the routine performance and over-reliance on MRI in active surveillance:

- There is no difference in upgrading when utilizing systematic (27%) versus MRI targeted surveillance biopsies (33%).

- There is no difference in upgrading if upfront MRI (23%) is performed compared to after diagnosis (19%)

- Progression missed by MRI but detected by systematic Bx in 31 – 36% of cases

- The negative predictive value is only 70 to 85%.

As such, Dr. Salami argued that an MRI should not be performed more frequently than every one to two years.

What are the guidelines statements for MRI use in active surveillance?

- ASCO (2016): “The AS protocol may include ancillary tests that are still under investigation. These could include mpMRI and genomic testing… mpMRI should not be used as a replacement for surveillance biopsy.”3

- AUA Guideline (2022), Statement 18: “In patients selecting active surveillance, clinicians should utilize multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) to augment risk stratification, but this should not replace periodic surveillance biopsy. (Expert Opinion)”4

An exciting development has been the use of tissue-based biomarkers in active surveillance. When such genomic tests are performed in patients with Grade Group 1 disease, the goal is to answer the question of whether high-grade disease is concurrently present but may have been missed. There are three possible scenarios as outlined below:

Commercially available molecular biomarkers include:

- Oncotype Dx Prostate

- Prolaris

- Decipher

- ProMark

The use of these tests in clinical practise have yielded mixed results, as demonstrated in multiple retrospective data analyses. These tests have not yet been prospectively tested or shown to improve long-term outcomes. As of yet, the routine ordering of molecular biomarkers in this setting is not recommended. These have been reflected in the most recent ASCO guidelines update:

- ASCO 2022 (Eggener et al, JCO, 2019):

- “Routine ordering of molecular biomarkers is not recommended.”

- “The Expert Panel endorses their use only in situations in which the assay results, when considered as a whole with routine clinical factors, are likely to affect a clinical decision.”

- For example: high volume Grade Group one, Grade Group one with abnormal DRE or high PSA density, and/or low-volume Grade Group two disease

This approach has similarly been mirrored by the AUA, with the most recent guidelines update recommending the following:

- Statement 2: Clinicians may selectively use tissue-based genomic biomarkers when added risk stratification may alter clinical decision making. (Expert Opinion).

- Statement 3: Clinicians should not routinely use tissue-based genomic biomarkers for risk stratification or clinical decision-making. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade B).

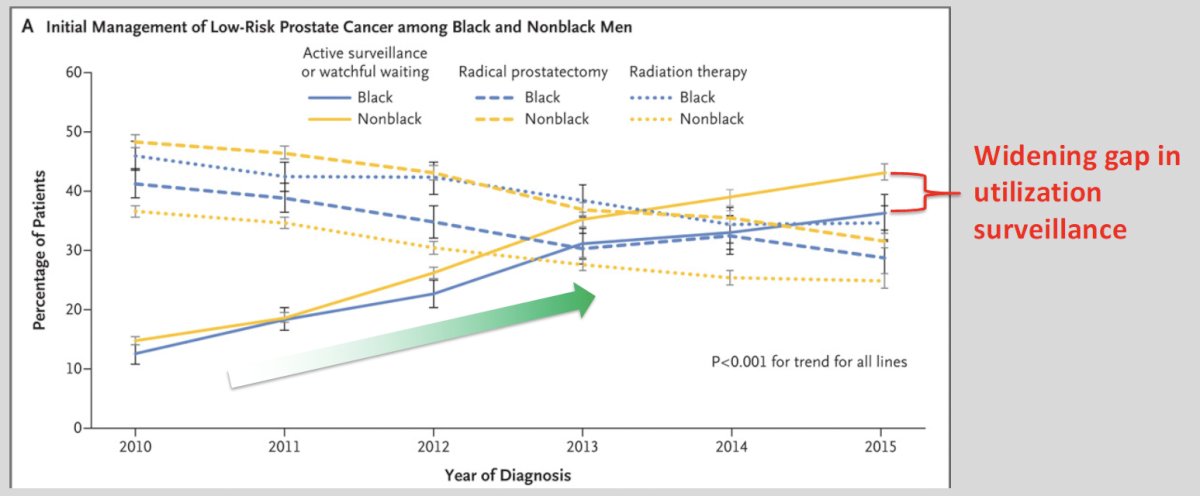

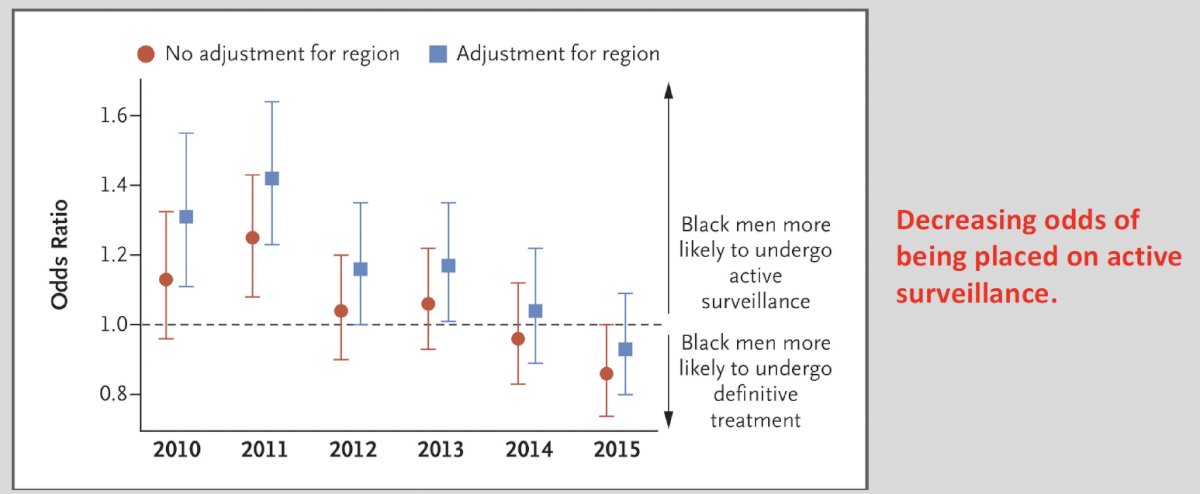

What are some select clinical situations that warrant special consideration? Dr. Salami noted the ‘where’ may apply to Black/African American patients and patients with pathogenic line variants (e.g., BRCA1/2, ATM). While Black/African American patients have historically been at higher risk of disease progression and mortality, this does not preclude active surveillance in well-selected patients. Unfortunately, it appears that active surveillance is being disparately under-utilized in low-risk black patients, as demonstrated by Butler et al. in 2019. While the utilization of active surveillance for such patients has increased between 2010 and 2015, the gap between Black and non-Black patients continues to widen.5

This trend does not appear to be improving, with Al Awamlh et al. demonstrating that between 2010 and 2015, Black men were progressively less likely to undergo active surveillance compared to their non-Black counterparts.6

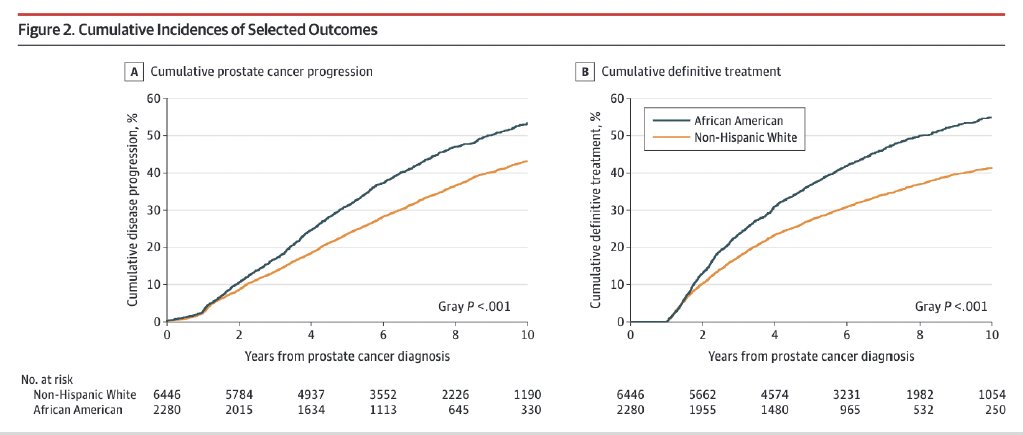

Although African American men, compared with non-Hispanic White men, have a significantly increased 10-year cumulative incidence of disease progression and definitive treatment, to date there are no demonstratable differences in the rates of metastases or prostate cancer-specific mortality.7

Whether these disparities are related to biologic variables (i.e., genetics), non-biologic factors (access, insurance, screening, primary care), or both remains to be determined.

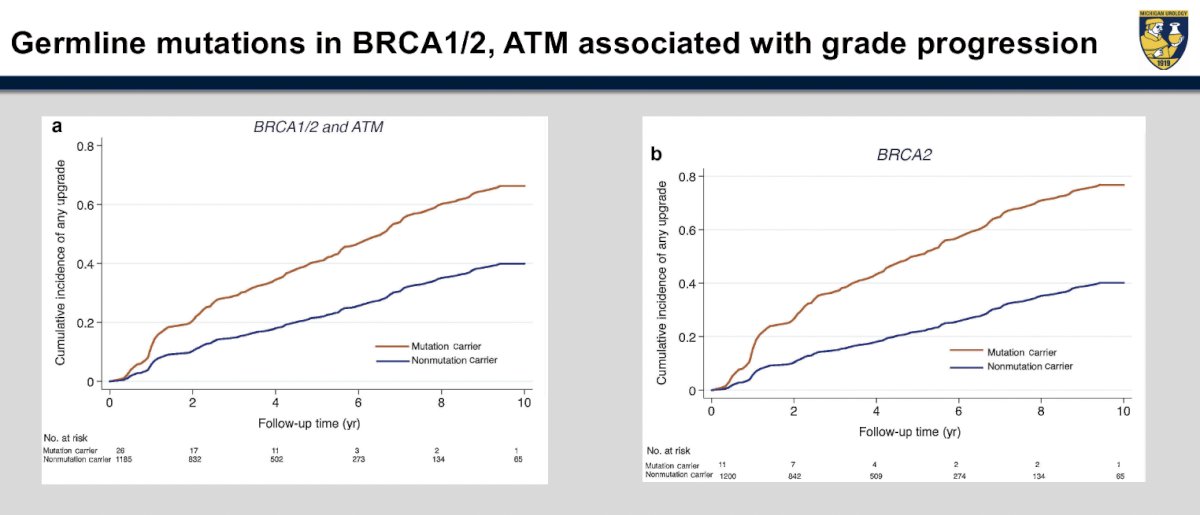

Patients with germline mutations such as BRCA1/2 and ATM undergoing active surveillance are at an increased risk of grade progression. Carter et al. demonstrated that upgrading occurred in 42% of such mutation carriers, compared to 23% of non-carriers.8 While presence of such mutations does not definitively preclude utilization of active surveillance, careful selection and close monitoring of such patients is advisable.

Finally, when should we de-escalate active surveillance regimens and transition to watchful waiting? This should be considered in older patients (i.e., 75 to 80 years), particularly those with a limited life expectancy <10 years and who have lower volume/grade disease. By increasing the interval between biopsies, amongst other modifications, we can balance the risk of missed disease progression and anxiety with the burden of surveillance testing.

Dr. Salami concluded with the following take home messages:

- Why? Reduce harm of treatment, and identify aggressive disease for treatment.

- What? Multimodal monitoring of prostate cancer patients.

- Who? Low- and select favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer.

- When? Testing intervals – PSA every 6 months, others every 1/2 – 5 years

- How? Use PSA/PSA density, biopsies, MRI, and biomarkers.

- Where? In office versus virtual visits.

- Active surveillance is safe and currently endorsed by the AUA, ASCO, SUO.

Presented by: Simpa Salami, MD, MPH, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

Written by: Rashid K. Sayyid, MD, MSc – Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Clinical Fellow at The University of Toronto, @rksayyid on Twitter during the 2023 Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) annual meeting held in Washington, D.C. between November 28th and December 1st, 2023

References:- Cooperberg MR, Meeks W, Fang R, et al. Time Trends and Variation in the Use of Active Surveillance for Management of Low-risk Prostate Cancer in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e231439.

- Rajwa P, Pradere B, Mori K, et al. Association of Negative Followup Biopsy and Reclassification during Active Surveillance of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Urol. 2021;205(6):1559-1568.

- Chen RC, Rumble RB, Loblaw DA, et al. Active Surveillance for the Management of Localized Prostate Cancer (Cancer Care Ontario Guideline): American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(18):2182-90.

- Eastham JA, Boorjian SA, Kirkby E. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO Guideline. J Urol. 2022;208(3):505-507.

- Butler S, Muralidhar V, Chavez J, et al. Active Surveillance for Low-Risk Prostate Cancer in Black Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):2070-2072.

- Al Awamlh B, Ma X, Christos P, et al. Active Surveillance for Black Men with Low-Risk Prostate Cancer in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2581-2582.

- Deka R, Courtney PT, Parsons JK, et al. Association Between African American Race and Clinical Outcomes in Men Treated for Low-Risk Prostate Cancer With Active Surveillance. JAMA. 2020;324(17):1747-1754.

- Carter HB, Helfand B, Mamawala M, et al. Germline Mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 Are Associated with Grade Reclassification in Men on Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;75(5):743-749.