(UroToday.com) The 2024 Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) annual meeting held in Dallas, between December 3 and December 6, 2024, was host to the Bladder Cancer Session II. Dr. Trinity Bivalacqua discussed Sexual Dysfunction and Radical Cystectomy.

Dr. Bivalacqua mentioned that Dr. Michaell Droller and Patrick Walsh were the first to describe the technique for nerve sparing in radical prostatectomy.

Sexual dysfunction after radical pelvic surgery may take up to 4 years to recover. Most of us are familiar with sexual dysfunction following radical prostatectomy (RP) and are also aware of its impact in bladder cancer (BCa) patients. Most patients may experience compromised erections, with diminished erection quality, and may require erection aids indefinitely, such as PDE5 inhibitors, intracavernous injections, MUSE, or vacuum erection devices (VED). Other sexual dysfunctions associated with RP include climacturia, penile shortening, Peyronie's disease, changes in orgasm, and an impact on couple sexual intimacy.

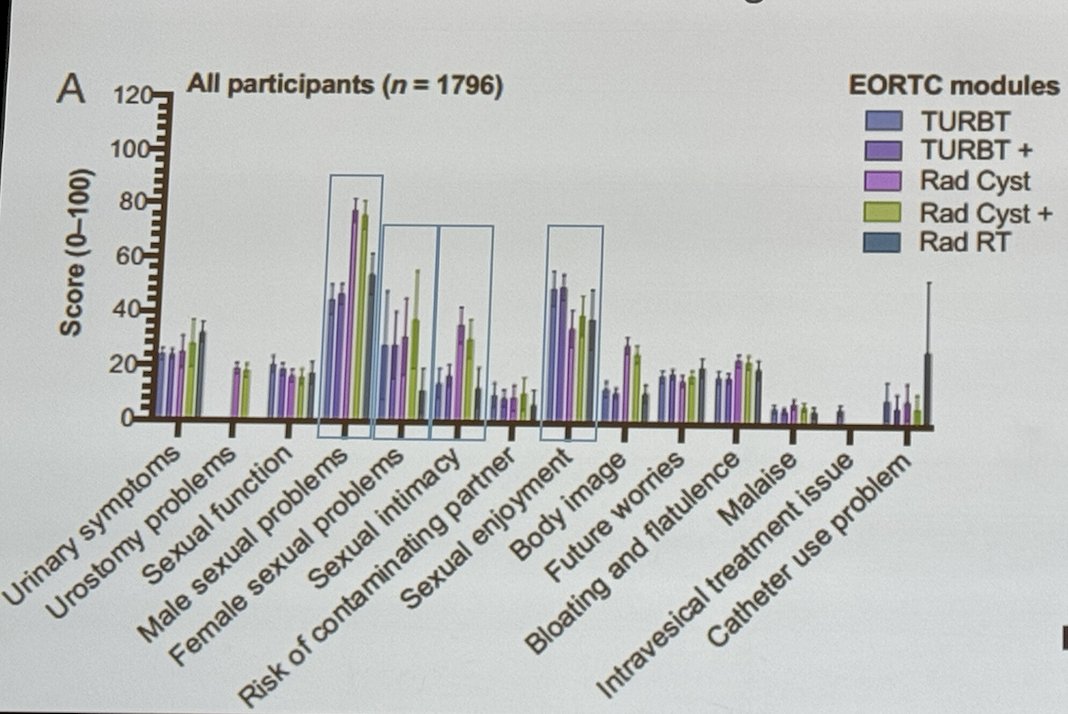

Jim Catto explored sexual problems across different surgeries for bladder cancer (BCa), including TURBT, radical cystectomy, and radiation. They found that sexual dysfunction was highly prevalent among males, with 39% reporting sexual intimacy problems, only 36% reporting sexual enjoyment, and of those, 28% reported female sexual problems.1

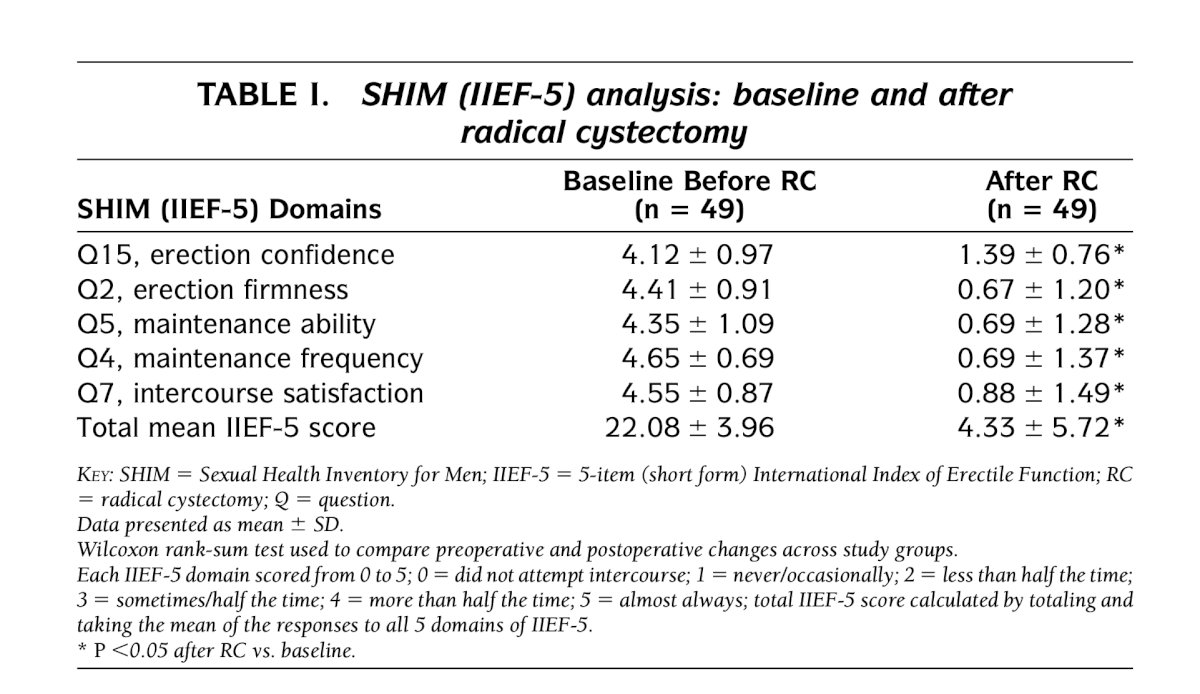

Dr. Bivalacqua presented a 20-year-old paper published in 2004. The baseline and follow-up data from 49 sexually active male patients (mean age 57.8 ± 9.1 years) undergoing radical cystectomy (RC) between 1995 and 2002 were obtained, with a mean follow-up of over 2 years. Of these, 16 (33%) had undergone nerve-sparing RC, and 38 (78%) had undergone orthotopic diversion. The data were assessed using the abridged 5-item International Index of Erectile Function questionnaire, the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM).

Notably, all these patients who were sexually active before surgery, none of them recovered erectile function after radical cystectomy. Additionally, only 2 out of 24 patients who were prescribed PDE5 inhibitors responded to the treatment.2

A study assessed patient-reported sexual function outcomes in male patients following radical cystoprostatectomy (RCP) and urinary diversion. The aim was to report sexual health outcomes using validated questionnaires, including the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5, SHIM) and supplemental questions about libido, orgasm, partner interest, and pre-operative counseling. A total of 137 patients were evaluated between 2017 and 2020, with a median age of 69 years at the time of cystectomy (IQR: 60-72) and a median follow-up duration of 17.3 months. The pre-operative IIEF score was 16.3

The study found that younger age, pre-operative erectile function, and nerve-sparing surgery were predictive of higher IIEF scores. Post-RC, the median libido score was 2 (severely impaired/low), and only 43% of sexually active men were able to achieve orgasm. Pre-operative counseling and nerve-sparing radical cystoprostatectomy were predictive of preserving orgasm.

The current medical management for erectile preservation or dysfunction includes:

- PDE5 inhibitor therapy.

- Intracavernous injection therapy (ICI)

- Vacuum Erection Device (VED)

- MUSE (intraurethral alprostadil)

- Experimental approaches - PRP, LiSWT, SCs

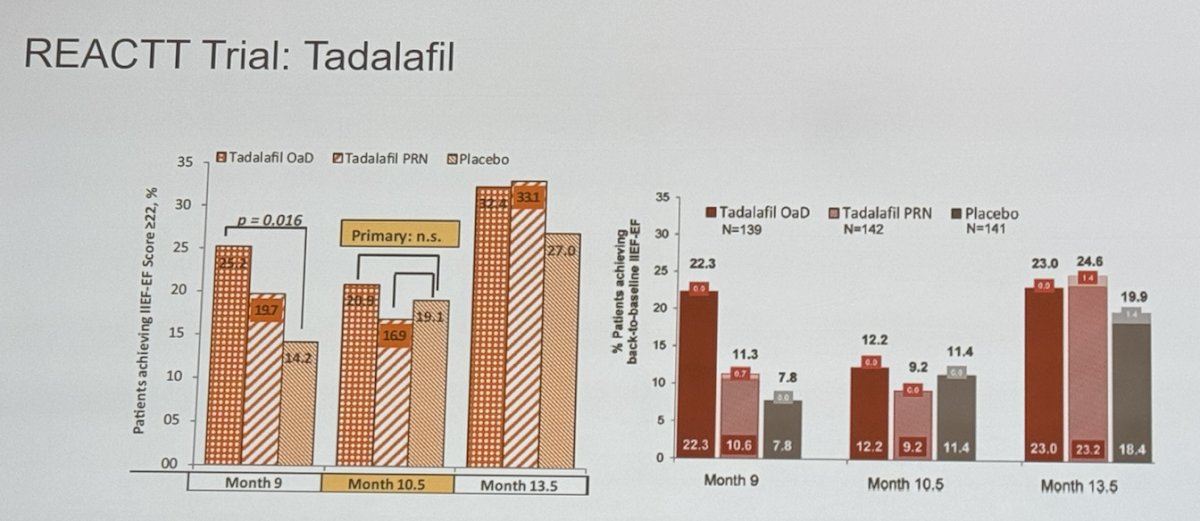

Unfortunately, PDE5 inhibitors (PDE5I) do not work effectively in our radical prostatectomy or cystectomy patients. There has been considerable interest in penile rehabilitation, which aims to preserve erectile tissue by using drugs or devices at or after radical prostatectomy to maximize erectile function recovery. However, evidence suggests that penile rehabilitation may not significantly improve outcomes and likely only provides psychological reassurance for both clinicians and patients. Despite its increased popularity, this approach does not substantially alter the recovery of erectile function in these patients and the most important factor is bilateral nerve sparing radical prostatectomy as shown below:

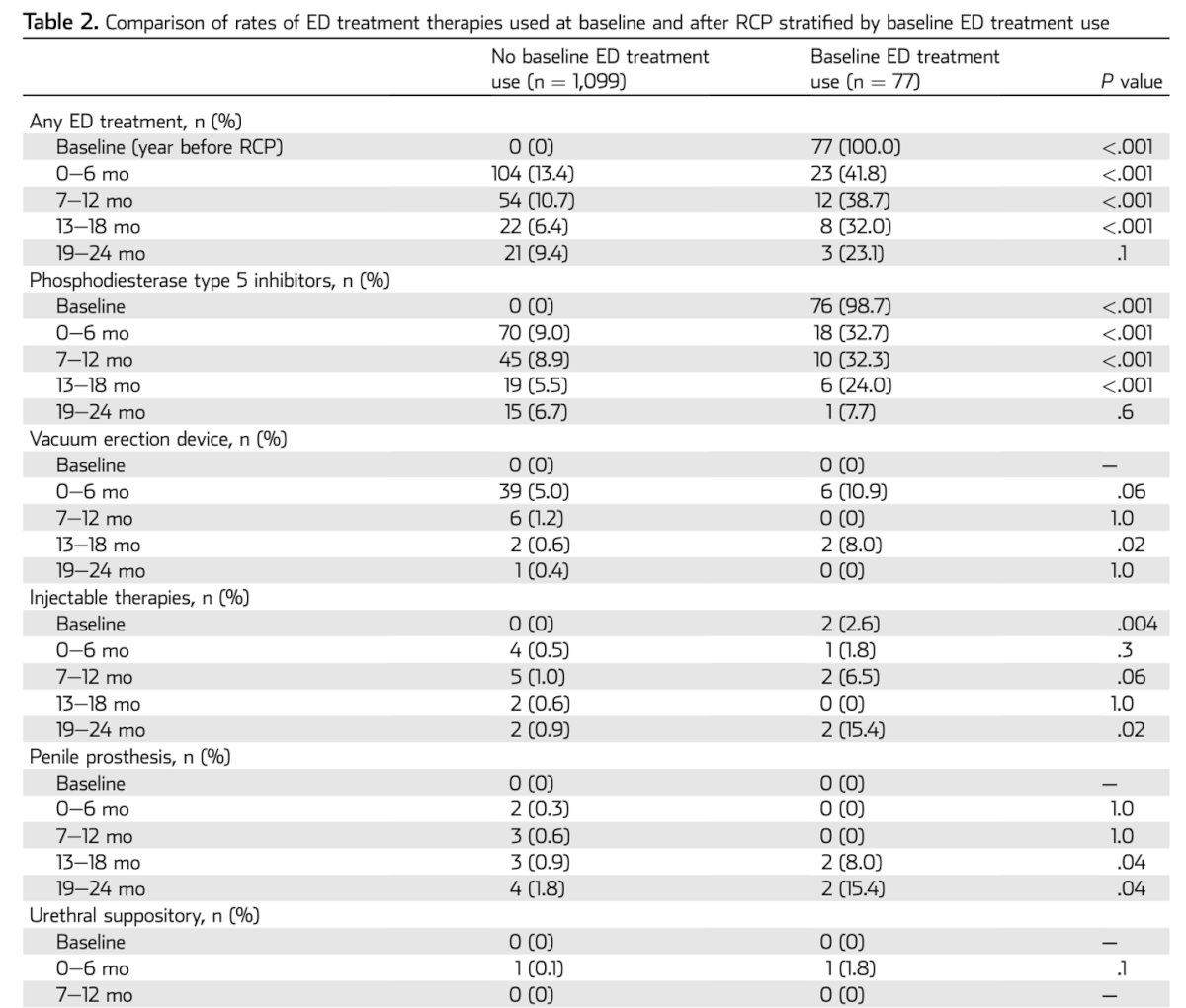

Dr. Bivalacqua discussed ED treatment following RC, presenting a study on the rates of ED treatment use (PDE5I, injectable therapies, urethral suppositories, VEDs, and penile prosthetics) in bladder cancer patients before and after RC. Interestingly, among those who were not using any ED treatment at baseline and had preserved sexual function, less than 10% of sexually active men were using PDE5I, regardless of the time since surgery.

This finding should raise alarms, as it indicates that we are either not prescribing ED treatments to our BCa patients or not actively inquiring about ED in this group. It highlights a significant gap in managing sexual health post-surgery, suggesting the need for more proactive screening and treatment of ED in this population.

Interestingly, in the multivariable model, predictors of ED treatment use at 0 to 6 months after RC were age younger than 50 years (OR = 3.17), baseline ED treatment use (OR = 5.75), neoadjuvant chemotherapy (OR = 1.72), and neobladder diversion (OR = 2.40).

Dr Bivalacqua concluded his male sexual dysfunction part of the presentation with the following key messages:

- In Male patients undergoing RC, baseline ED is more common with poor return of erectile function

- Major impact on sexual function including intimacy, orgasm, and body image

- Nerve sparing approach is less common and ED treatments are not offered to RC patients.

- We must further study and investigate barriers, education, and training to address sexual dysfunction following RC

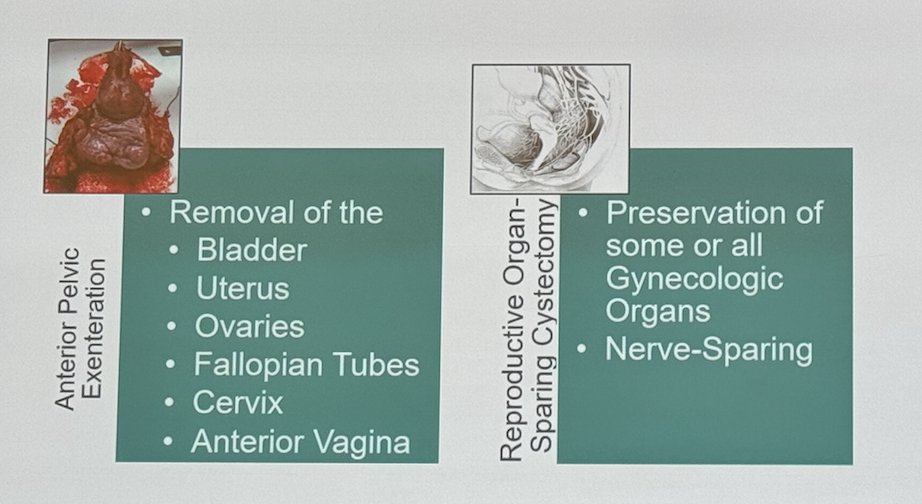

To discuss female sexual dysfunction after radical cystectomy, it's important to understand two surgical approaches. One is anterior pelvic exenteration, which involves the removal of the bladder, uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, cervix, and anterior vagina. The other is reproductive organ-sparing cystectomy, which preserves these reproductive organs.

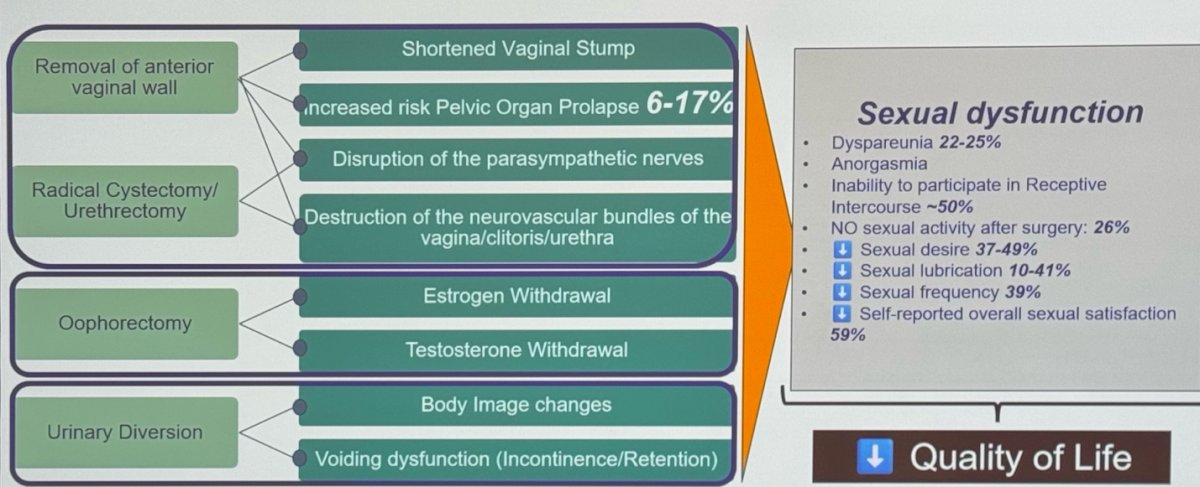

The implications of not using reproductive organ-sparing approaches are vast, as illustrated in the figure below. Given the extent of the surgery, the removal of the ovaries alone leads to estrogen and testosterone withdrawal, which has numerous consequences. Furthermore, sexual dysfunction in women is not uncommon post-surgery. Approximately 22-25% experience dyspareunia, and up to 50% report complete inability to participate in receptive intercourse. Furthermore, up to a third have no sexual activity after surgery. These issues significantly impact the quality of life of our patients.

Complete reproductive organ-sparing RC involves mobilization of the bladder while preserving the parametrial structures including the autonomic nerves and vasculature which are located laterally to the vagina.

Dr. Bivalacqua mentioned it is well known that the extent of surgery significantly affects women's sexual ability. The loss of the vagina, a shortened vagina, and the loss of the cervix can interfere with the ability to have intercourse. The loss of ovaries pushes women into a post-menopausal state, and the loss of the distal urethra and the anterior wall of the vagina diminishes orgasmic function.

Women having to go through a difficult recovery after cystectomy may not be interested in restarting sexual life until several months after surgery. Additionally, urinary diversion may affect body image and sexual confidence.

Many outstanding questions remain before we can offer reproductive organ-sparing RC to all women. Is it oncologically safe? Is nerve-sparing important and effective in women? Are current urologic oncologists educated and trained to perform this type of surgery? How does it impact the patient and their partners? Dr. Bivalacqua tried to answer some of these questions, but many still need to be addressed.

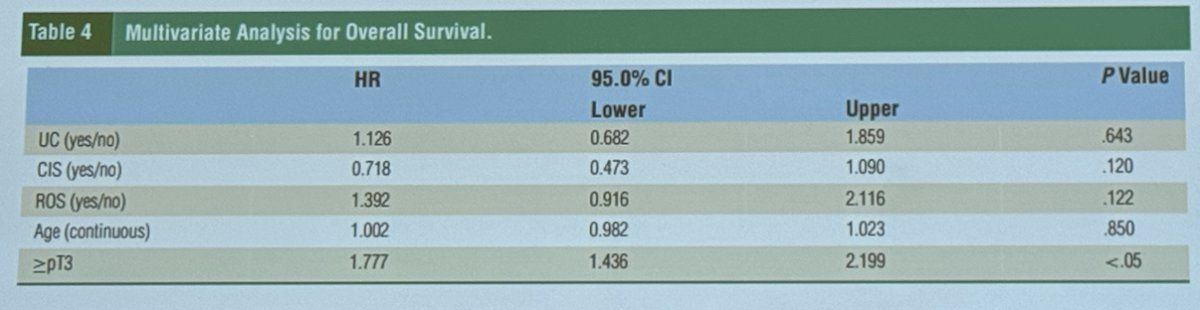

In a retrospective cohort analysis from Johns Hopkins between 2000-2020, 289 women who underwent cystectomy were identified: 188 underwent reproductive organ-sparing (ROS) cystectomy compared to 101 who did not. The study found no difference in recurrence-free and cancer-specific survival between the groups. However, on multivariate analysis for overall survival, a pathologic stage of ≥ pT3 increased the risk of mortality with ROS (HR 1.77, 95% CI 1.436-2.199). Despite this, ROS cystectomy remained safe in cases of variant histology. The preoperative and intraoperative assessments are key for patient selection and should drive decision-making.

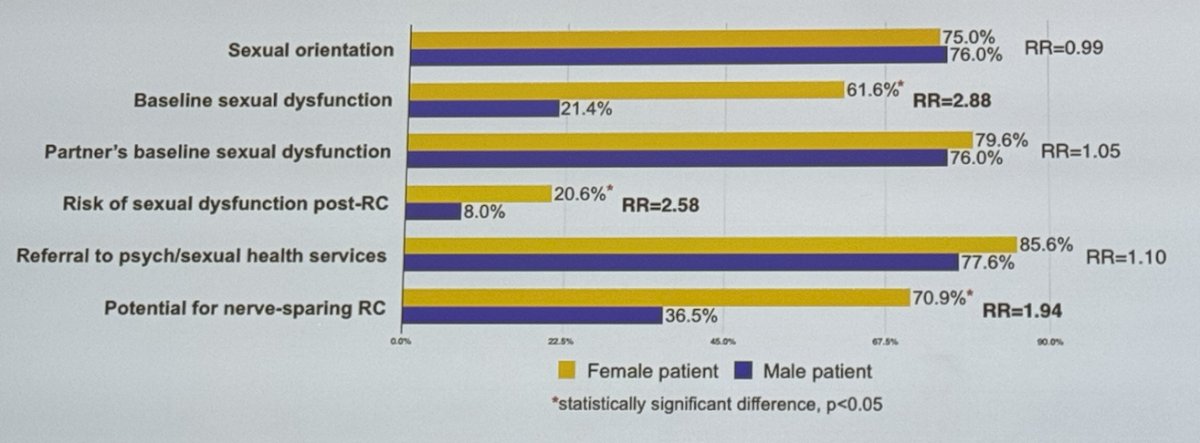

Natasha Gupta conducted a cross-sectional survey of urologic oncologists in the U.S., administered anonymously and electronically via the Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO), to assess national practice patterns among urologists performing female radical cystectomy. The survey queried sexual health counseling practices, barriers to counseling female patients, operative techniques, and compared counseling for male vs. female patients. It also assessed associations between provider characteristics and counseling and operative techniques.5

Notably, 76% of respondents correctly identified the location of the neurovascular bundle in women, but 79% do not routinely spare the uterus/cervix if premenopausal, and 67% do not routinely spare the neurovascular bundle if premenopausal. Additionally, 49% do not routinely spare the ovaries if premenopausal.5

Moreover, 70% of providers do not routinely discuss nerve-sparing RC with sexually active women, and 36% do not discuss it with men. Baseline sexual dysfunction is acknowledged in 82% of women and 21% of men. Additionally, 41.7% of providers do not routinely counsel sexually active female patients about the potential for reproductive organ-sparing RC.

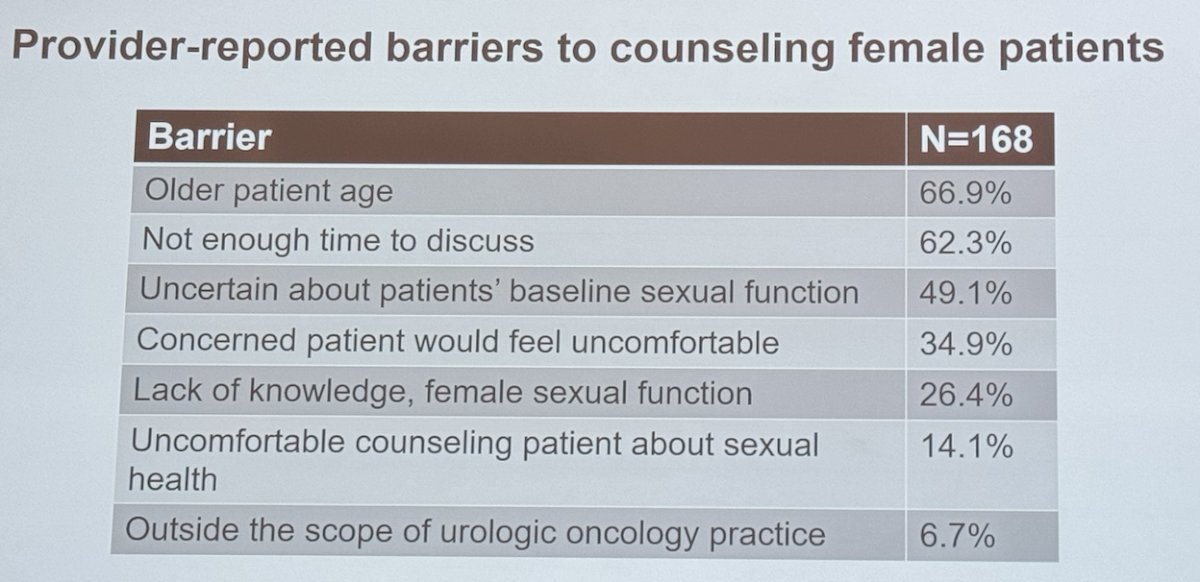

Providers reported the following barriers to counseling female patients, in order of frequency: older age, not enough time during the clinic visit to discuss these issues, and uncertainty about patients' baseline sexual function, as shown below:

Dr. Bivalacqua concluded this section of the presentation focusing on female sexual dysfunction and cystectomy with the following takeaways:

- Providers are less likely to counsel female patients about sexual health than male patients; current counseling is inadequate

- Providers do not routinely perform ROS or nerve-sparing RC even in cases of clinically-localized MIBC or NMIBC; practice is widespread

- Reducing barriers to counseling female patients about sexual health and performing reproductive organ-preserving RC is important to improve functional outcomes among female patients

- New trial results should address questions related to female sexual dysfunction post-RC

Presented by: Trinity J. Bivalacqua, MD, PhD, Director of Urologic Oncology and Co-Director of the Genitourinary Cancer Service Line in the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Written by: Julian Chavarriaga, MD – Urologic Oncologist at Cancer Treatment and Research Center (CTIC) Luis Carlos Sarmiento Angulo Foundation via Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Fellow at The University of Toronto. @chavarriagaj on Twitter during the 2024 Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) annual meeting held in Dallas, between the 3rd and 6th of December, 2024.

References:

- Catto JWF, Downing A, Mason S, Wright P, Absolom K, Bottomley S, Hounsome L, Hussain S, Varughese M, Raw C, Kelly P, Glaser AW. Quality of Life After Bladder Cancer: A Cross-sectional Survey of Patient-reported Outcomes. Eur Urol. 2021 May;79(5):621-632. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.01.032. Epub 2021 Feb 10. PMID: 33581875; PMCID: PMC8082273.

- Zippe CD, Raina R, Massanyi EZ, Agarwal A, Jones JS, Ulchaker J, Klein EA. Sexual function after male radical cystectomy in a sexually active population. Urology. 2004 Oct;64(4):682-5; discussion 685-6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.05.056. PMID: 15491700.

- Loh-Doyle JC, Bhanvadia SK, Han J, Ghodoussipour S, Cai J, Wayne K, Schuckman AK, Djaladat H, Daneshmand S. Patient Reported Sexual Function Outcomes in Male Patients Following Open Radical Cystoprostatectomy and Urinary Diversion. Urology. 2021 Nov;157:161-167. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2021.07.004. Epub 2021 Jul 21. PMID: 34298032.

- Chappidi MR, Kates M, Sopko NA, Joice GA, Tosoian JJ, Pierorazio PM, Bivalacqua TJ. Erectile Dysfunction Treatment Following Radical Cystoprostatectomy: Analysis of a Nationwide Insurance Claims Database. J Sex Med. 2017 Jun;14(6):810-817. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.04.002. Epub 2017 Apr 29. PMID: 28460994.

- Gupta N, Kucirka LM, Semerjian A, Wainger J, Pierorazio PM, Herati AS, Bivalacqua TJ. Comparing Provider-Led Sexual Health Counseling of Male and Female Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy. J Sex Med. 2020 May;17(5):949-956. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.01.025. Epub 2020 Mar 12. PMID: 32171630.