However, with the advent of modern endourology, Retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) has become a popular choice for the management of renal stones and is widely accepted as a safe procedure even in anomalous anatomy. The question remains whether these minimally invasive alternatives can stand against these traditional techniques in the case of diverticular calculi. On top of comparing both methods with our global multicentre match paired study, we wanted to highlight the technical differences in methods used by specialists in reference to identifying the diverticular opening, accessing the diverticulum as well as lithotripsy and exit strategy.

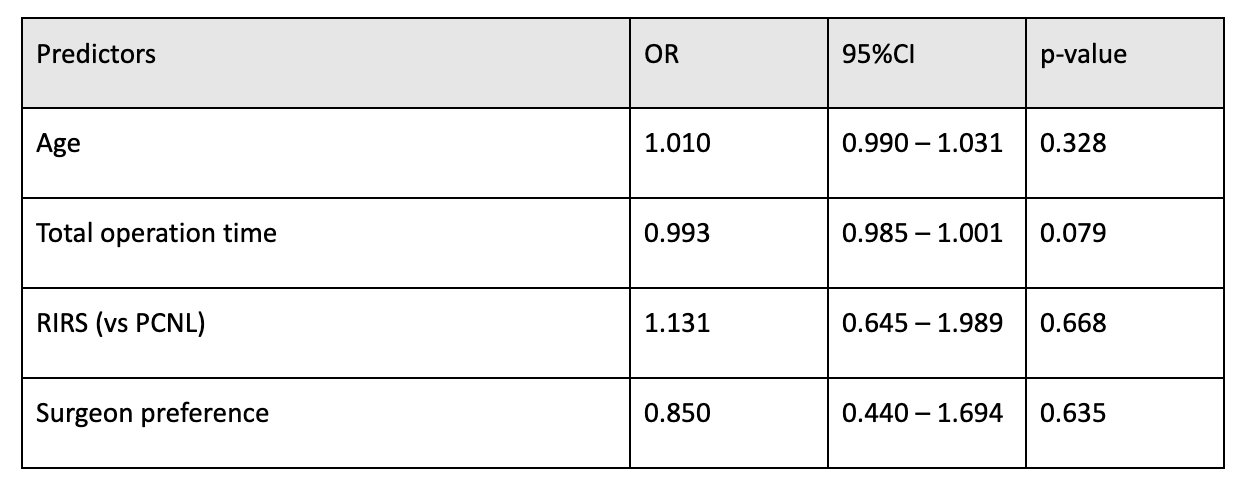

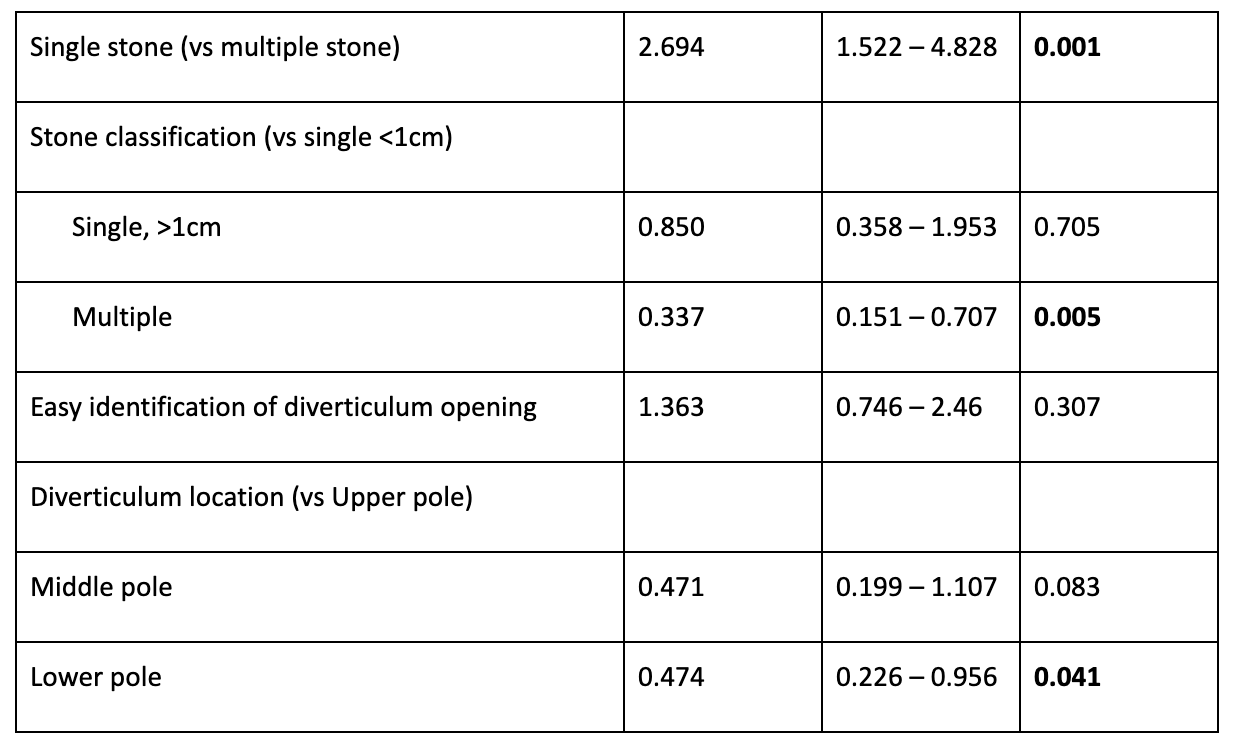

Retrospective data was collated spanning 11 countries representing various ethnic and cultural groups across both western and eastern populations. Propensity-score matching was performed between groups who underwent mini-PCNL (PCNL) vs RIRS for pre-operative variables including demographics, stone characteristics, intra-operative techniques as well as post-operative complications. Where available, data was compared regarding how the diverticulum was identified, methods for access as well as exit strategies. Our analysis shows no significant difference in SFR between both groups (71.5% in PCNL vs 74% in RIRS, p = 0.775) as well as similar re-intervention rates for residual fragments, regardless of stone size, number, and location of the diverticulum. Factors influencing outcomes include multiplicity of stones but interestingly not stone size. The location of the diverticulum also was an important factor, with higher odds of residual fragments in lower pole diverticular stones (OR 0.474, p < 0.041). Conversion to ECIRS for an endoscopic combined approach was performed for 4.7% of PCNL cases and 6.5% of RIRS cases.

Univariate Analysis of SFR (After PSM)

Some notable differences were found regarding intra-operative techniques. In PCNL, typically the diverticular neck is identified with contrast administration antegrade or retrograde through infusion of indigo carmine dye. In RIRS, the methylene blue dye is classically used if the diverticulum is not identified with contrast. Interestingly in our study, the blue-dye test was used more frequently in the PCNL group (8.4%) than the RIRS group (4.9%) – potentially indicating that a combination of direct visualization with the flexible scope and guidewire introduction under vision may preclude the use of these techniques. With regards to fulguration of the diverticulum, evidence also remains controversial. There have been reports of 87.5% obliteration at 3 months follow up with higher obliteration rates than dilation alone. Others believe electrocautery would traumatize the calyceal lining. In our series, none of the specialists used fulguration or electrocautery. Instead, laser infundibulotomy was done for 20.8% of PCNL patients and 63.1% in RIRS patients. Unfortunately, in our series, no laser settings were reported, but this remains the first real-world large case series advocating the use of laser for both approaches as compared to electrocautery in the past.

Overall, both PCNL and RIRS present safe options for the effective management of calyceal diverticulum stones with similar SFR. Urologists may determine the best modality based on the number of stones as well as the location of the diverticulum but also based on their own technical proficiencies. Although PCNL currently has slightly longer hospitalization duration (3.86 ± 1.94 vs 1.04 ± 0.20 days for RIRS group; p <0.001) and bleeding-related complication rates, future further miniaturization may still alter the playing field in this rapidly-developing arena. Modern endourologists should always be adept at multiple techniques for various circumstances, and flexible to change the operative plan in the event of any challenges.

Written by: Vineet Gauhar,1 Olivier Traxer,2 Shauna Jia Qian Woo,3 Khi Yung Fong,4 Deepak Ragoori,5 Amish Wani,5 Boyke Soebhali,6 Abhay Mahajan,7 Maheshwari Pankaj,8 Nariman Gadzhiev,9 Yiloren Tanidir,10 İlker Gokce Mehmet,11 Cemil Aydin,12 Yakup Bostanci,13 Saeed Bin Hamri,14 Fahad R Barayan,15 Mriganka Mani Sinha,16 Takaaki Inoue,17 Jeremy Yuen-Chun Teoh,18 Daniele Castellani,19 Bhaskar K Somani,16 Ee Jean Lim3

- Department of Urology, Ng Teng Fong Hospital, NUHS, Singapore, Singapore.

- Lithiase Urinaire, Sorbonne Université, AP-HP, Hôpital Tenon, Paris, France.

- Department of Urology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore Health Services, Singapore, Singapore.

- Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

- Department of Urology, Asian Institute of Nephrourology, Hyderabad, India.

- Department of Urology, Abdul Wahab Sjahranie Hospital Medical Faculty, Muliawarman University, Samarinda, Indonesia.

- Department of Urology, Sai Urology Hospital, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India.

- Department of Urology, Fortis Hospital Mulund, Mumbai, India.

- Department of Urology, Saint-Petersburg State Medical University, Saint-Petersburg, Russia.

- Department of Urology, Marmara University School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Department of Urology, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

- Department of Urology, Hitit University School of Medicine, Training and Research Hospital, Corum, Turkey.

- Department of Urology, Ondokuz Mayis University, Samsun, Turkey.

- Department of Urology, Advanced Laser Endourology at King Abdulaziz National Guard Medical City Saudi Arabia, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

- Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- Department of Urology, University Hospital NHS Trust, Southampton, UK.

- Department of Urology and Stone Center, Hara Genitourinary Hospital, Kobe, Japan.

- Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, S. H. Ho Urology Centre, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

- Department of Urology, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Ospedali Riuniti di Ancona, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy.

- Timmons JW, Malek RS, Hattery RR, Deweerd JH. Caliceal diverticulum. J Urol. 1975 Jul;114(1):6–9.

- Ito H, Aboumarzouk OM, Abushamma F, Keeley FX. Systematic Review of Caliceal Diverticulum. J Endourol. 2018 Oct;32(10):961–72.

- García Rojo E, Teoh JYC, Castellani D, Brime Menéndez R, Tanidir Y, Benedetto Galosi A, et al. Real-world Global Outcomes of Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery in Anomalous Kidneys: A High Volume International Multicenter Study. Urology. 2022 Jan;159:41–7.

- Lim EJ, Teoh JY, Fong KY, Emiliani E, Gadzhiev N, Gorelov D, et al. Propensity score-matched analysis comparing retrograde intrarenal surgery with percutaneous nephrolithotomy in anomalous kidneys. Minerva Urol Nephrol.

- Monga M, Smith R, Ferral H, Thomas R. Percutaneous ablation of caliceal diverticulum: long-term followup. J Urol. 2000 Jan;163(1):28–32.