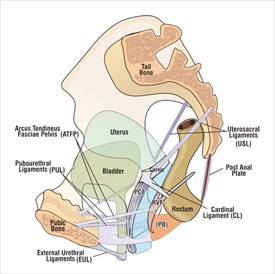

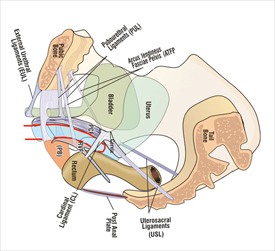

BERKELEY, CA (UroToday.com) - The suspensory ligaments play a key role in the support of the vagina, bladder, uterus, and rectum (Figure 1).[1] The utero-sacral (USL) and cardinal ligaments (CL) suspend the uterus, and by virtue of their attachments to vaginal fascia (PCF & RVF), the bladder base and anterior wall of rectum (Figure 1).[1] The USLs suspend all three organs from above (bladder, uterus and rectum), much like a tent pole suspends the apex of a tent (Figure 1).

The biomechanics of the vagina and its suspensory ligaments

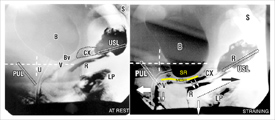

An understanding of the biomechanics of the vagina and its suspensory ligaments is vital to understanding the use of mesh tapes and sheets in pelvic reconstruction. The vagina, with an estimated breaking strain of approximately 60 mg/mm2,[2] has little inherent strength. It is essentially an elastic membrane which moves forwards and backwards during urethral closure, micturition,[1] and intercourse (Figures 2, 3). The suspensory strength of the anterior vagina is a function of its ligamentous attachments, which have an estimated breaking strain of approximately 300 mg/mm2.[2] Think of the bladder sitting on a plaster board ceiling (vagina) supported by ceiling joists (ATFP and cardinal ligaments) with the whole lot supported by the utero-sacral ligaments (the side walls of the house) (Figure 1). If the ceiling joists are weak, the ceiling will sag (cystocele). A similar analogy holds for the posterior vaginal wall and rectocele, with the perineal body (PB) supporting 50% of the posterior vaginal wall.[3]

Level 2 must remain elastic and mobile so as to allow the directional vectors to function (Figure 3). If large mesh sheets are inserted into the organ spaces at level 2, between vagina and bladder, anteriorly, and vagina and rectum posteriorly, they create a collagenous reaction which glues the organs to the vagina. This will inhibit the independent antero-posterior movements so essential for vaginal function, (Figure 3) and for sexual intercourse (Figure 2). If the schematic penis (Figure 2) stretches a vagina rendered sufficiently non-distensile because it is tethered to the the rectum by large mesh, it may cause dyspareunia and rectal pain, as the organs are innervated by visceral nerves which are especially sensitive to distension.

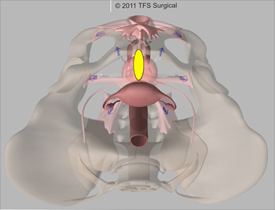

Modus operandi of the TFS

The neoligaments created by the TFS (Figure 4) mimic exactly the natural ligaments supporting the vagina and the organs at level 3 distally and level 1 proximally, attaching the vagina to the pelvic skeleton. As no tapes are inserted into level 2, level 2 can distend freely during intercourse and organ closure and emptying. Weak ligaments cannot be repaired by suturing, and need to be reinforced by a precisely applied TFS tape. The TFS tape stimulates the deposition of collagen which forms an artificial neoligament to reinforce the ligaments . A good analogy is a plaster board (vagina) supported by ceiling joists (ligaments).

Cure of OAB symptoms by the TFS cardinal/utero-sacral sling

We found that repairing the utero-sacral/cardinal ligament complex with the TFS mini sling also cured OAB symptoms such as frequency, urgency, and nocturia, validating the findings of a previous study.[4] The anatomical rationale for this is explained as follows: the backward/downward vectors, (arrows, Figure 3), stretch the vaginal membrane backwards and downwards to support the bladder base stretch receptors ‘SR’, preventing them from firing off prematurely. The vectors need to contract against a firm utero-sacral ligament (USL) and a firm pubo-urethral ligament (PUL). If the USL, CL or PUL are lax, the vector forces weaken,* and the stretch receptors cannot be supported, and fire off at a low bladder volume. The patient experiences this as urgency, frequency, and nocturia.

*Like a trampoline, even one loose spring will prevent tightening of the trampoline membrane.

View a related surgical video.

References:

- Petros PEP The Integral Theory System, A simplified clinical approach with illustrative case histories. (2010) Pelviperineology 29: 37-51

- Yamada H. Aging Rate for the Strength of Human Organs and Tissues. Strength of Biological Materials, Williams & Wilkins Co, Balt. (Ed) Evans FG. (1970); 272-280.

- Abendstein B, Petros P. E. P, Richardson P. A. Goeschen K , Dodero D. The surgical anatomy of rectocele and anterior rectal wall intussusception. Int Urogynecol J 2008.19, 5; 513-7

- Petros PEP, Richardson PA TFS posterior sling improves overactive bladder, pelvic pain and abnormal emptying, even with minor prolapse –a prospective urodynamic study. (2010) Pelviperineology 29: 52-55

Written by:

Yuki Sekiguchia and Peter Petrosb as part of Beyond the Abstract on UroToday.com. This initiative offers a method of publishing for the professional urology community. Authors are given an opportunity to expand on the circumstances, limitations etc... of their research by referencing the published abstract.

aYokohama Motomachi Women’s Clinic LUNA, 3-115, Hyakudan-kan 5F, Motomach, Nakaku, Yokohama 231-0861, Japan

bUniversity of NSW Academic Dept. of Surgery, St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney, Australia

More Information about Beyond the Abstract