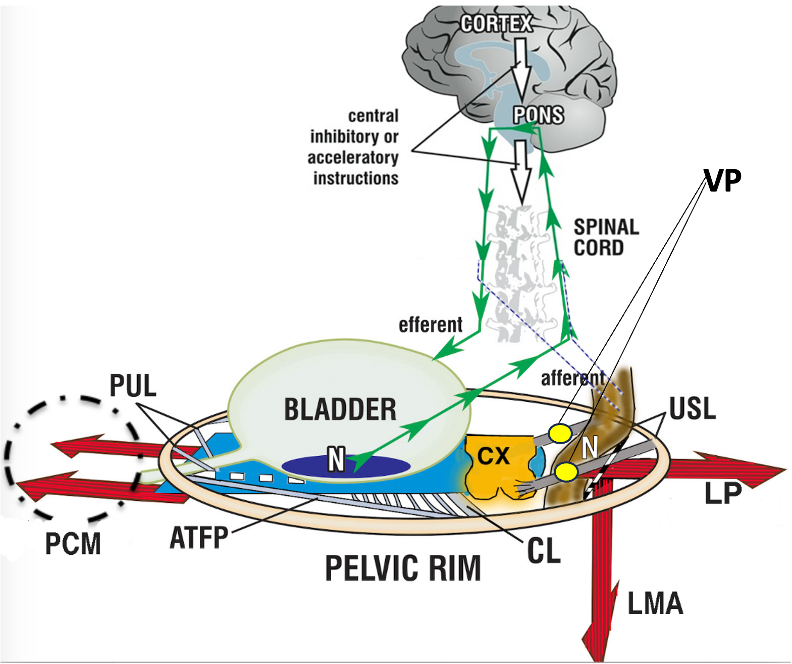

Fundamental to these high cure rates is a change in thinking: bladder function is not only from the organ (bladder), but also from outside it, from pelvic muscles contracting against competent suspensory ligaments, mainly pubourethral (PUL) and SSL/USL (sacrospinous/uterosacral) to close urethra, open it for micturition, and control premature activation of micturition (urge incontinence) Figure 1.1,2

Figure 1 Binary cortico/peripheral control of bladder and bowel. System in normal closed mode. Binary cortico/peripheral control of bladder and bowel is from stretch receptors (N) in the bladder and anorectum which have similar functions: they send afferent signals of fullness (green arrows) to evacuation centers in the brain. Anatomical damage to any part of the system may interfere with the binary control of all bladder and anorectal closure and opening functions, with ligaments being the most vulnerable because their structural collagen can alter during delivery and old age. Evacuation requires active opening of the posterior wall of the urethra and anorectum (broken lines) by LP/LMA prior to organ contraction.

PCM= pubococcygeus muscle; LP= levator plate; LMA= conjoint longitudinal muscle of the anus; PUL=pubourethral ligaments; USL = uterosacral ligaments; N=urothelial stretch receptors; CX = cervix; CL = cardinal ligament; ATFP = arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. VP=visceral pelvic plexus.

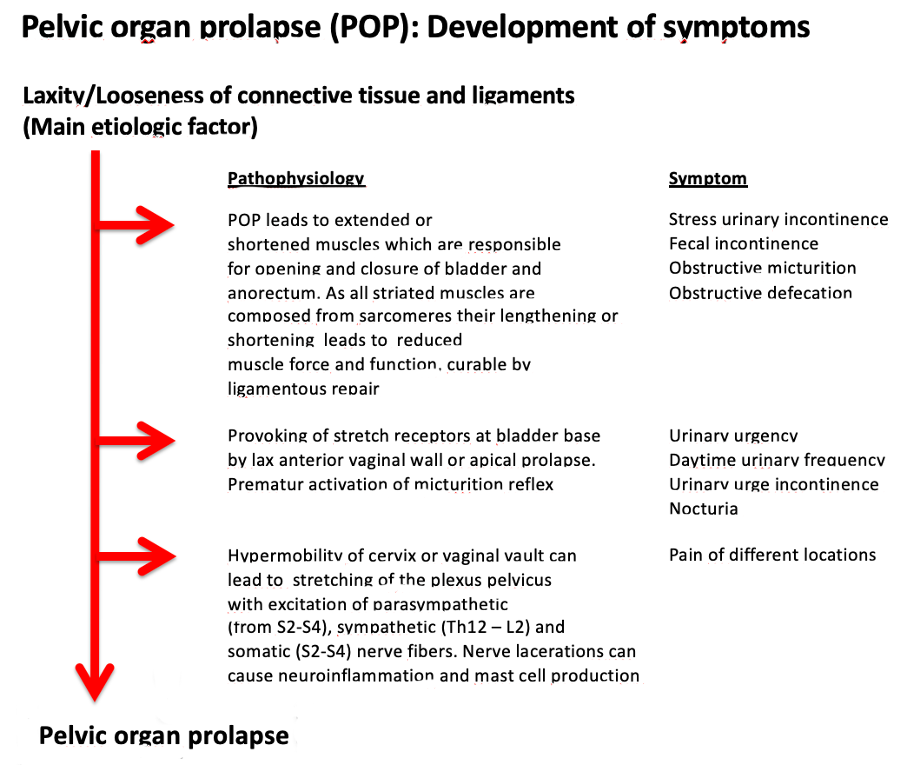

Pathophysiology of symptom development (Figures 1&2):

The pelvic floor consists of supporting connective tissue structures which hold the organs and define functional insertion points/areas of the main muscles M. pubococcygeus (PCM), levator plate (LP), longitudinal muscle of the anus (LMA) and M. puborectalis (PRM).2

Stress urinary continence control is achieved by contraction of the rhabdosphincter (a small, horse-shoe-shaped striated muscle complex at mid urethra), but mainly by contraction of PCM and PRM muscles forward, LP backward, and LMA downwards. These actions close the urethra distally and also, at the bladder neck, by angulating the bladder (1, 2). Intact pubourethral ligaments are required for all these actions.1,2

Micturition is not only achieved by relaxation of the rhabdosphincter but also of the PCM (broken circle, figure 1). Furthermore, active opening by contraction of the LP and LMA is required to open the bladder neck prior to evacuation.1-3 Without this active opening, micturition could only be started with 100-fold bladder pressure if it relied only on intrabdominal pressure to open the urethra.4

Fecal continence is not only provided by anal sphincter action but also by contraction of LP, LMA, and PRM thus creating the anorectal angle. With reference to Figure 1, forward contraction of PRM behind the anorectal angle, (not shown) stabilizes the rectum, and allows LP/LMA to rotate the rectum around PRM to close the anorectal angle. For normal defecation, relaxation of PRM, anal sphincter, and contraction of LP and LMA opens the anorectum prior to rectal contraction (broken lines, figure 1).

Laxities of the ligaments (main ligaments are pubourethral and uterosacral ligaments) and connective tissues of the pelvic floor, lead to effective lengthening of the muscles which contract against them, (large arrows, figure 1). As these muscles are composed of sarcomeres, the muscle force is rapidly diminished when their length is altered. As a consequence, the function of these muscles is reduced, and stress urinary incontinence, obstructive micturition, fecal incontinence, and/or obstructive defecation can occur. It follows, that ligamentous reconstruction can rapidly improve muscle forces and cure symptoms, Tables 1 & 2.1

Lax anterior vaginal wall with or without apical descent can provoke the stretch receptors of the bladder base “N”, figure 1, already with low bladder volumes so that symptoms of urinary urgency, daytime urinary frequency, urgency urinary incontinence, and nocturia can be triggered. Surgical stabilization of the anterior vaginal wall and the apex posteriorly can cure these symptoms, Tables 1.1,5,6

Hypermobility of the cervix or vaginal vault can stretch the nerve fibers of the pelvic visceral plexuses, VPs, figure 1, which contain sympathetic fibers (T11-L2) and parasympathetic fibers (S2-S4), which can cause pain in different locations. Based on the cure of chronic pelvic pain by USL ligament repair7 or cervical stabilization,1 a likely pathogenesis is unsupported VP junctions may fire off de novo impulses to the brain which are interpreted as pain from the end organ itself.4 Nerve fiber lacerations can induce neuroinflammation and mast cell production.1

Figure 2: Etiology and pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse and development of symptoms.1

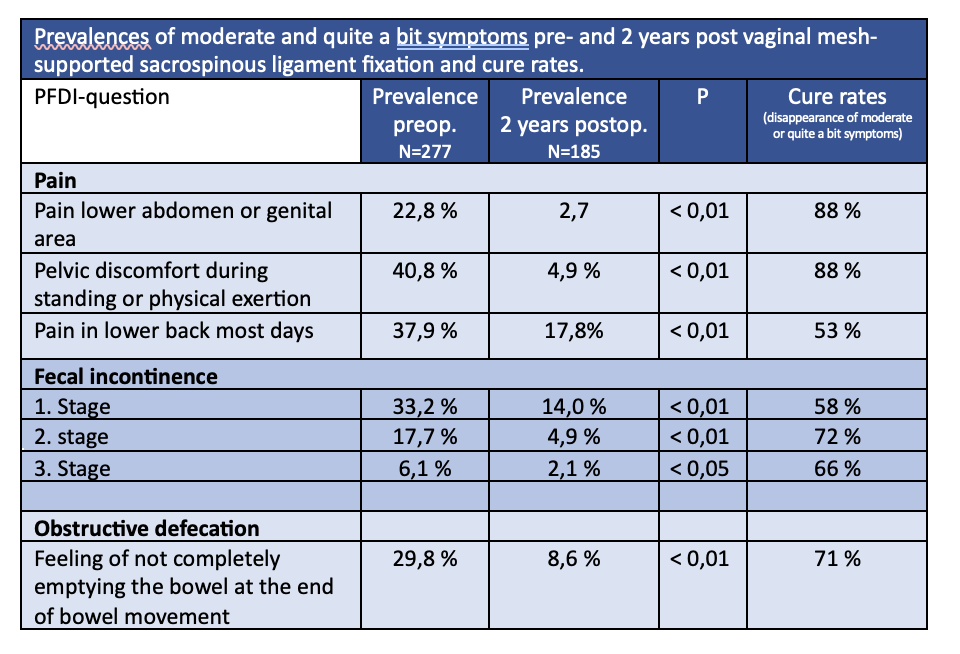

Symptom cure rates after mesh-supported sacrospinous ligament fixation.

Tables 1 and 2 show prevalences of "moderate” and “quite a bit” symptoms in women with POP-Q-stages 2-4 pre and 2 years post-vaginal POP-repair using the Elevate system, which firmly anchors the apical ligaments(USL) to the SSL. In those women who had POP-Q stage 0-1 at 6, 12, and 24 months and in each compartment (anterior, apical, and posterior) postoperatively (Responder) cure rates of 82 % (for urinary urgency incontinence) and 92 % (for nocturia) and 87 % for weak stream/take long to empty the bladder were observed. All others (non-responders) had minor cure rates of 46 %, 39 %, and 50 % respectively.

Prevalences of moderate or quite a bit symptoms pre- and 2 years post vaginal mesh-supported sacrospinous ligament fixation and cure rates.

Table 1. Surgical cure rates of symptoms of urinary urgency incontinence, nocturia, and obstructive micturition in women with pelvic organ prolapse, stages 2 – 4. Surgical success of symptom cure was independent of the POP stage. Responder: those women who have POP-stage 0 or 1 in each compartment (anterior, apical, and posterior) at 6, 12, and 24 months postoperatively. Non-Responder: all others, who developed 2nd stage cystoceles in 62,7 %, 2nd stage rectoceles in 27,1 %, apical prolapse 2.-4.stage in 13,2 %.6

Cure rate differences between Responders* and Non-Responders are significant (p < 0,01).

PFDI: Pelvic Floor disorder inventory (questionnaire).

Data from the Propel study (ClinicalTrials.gov-Identifier: NCT00638235)1,5,6,8

Table 2 shows that pain in different locations and modalities could be cured in 53 % (back pain) and 88 % (pain lower abdomen or genital area, pelvic discomfort during exertion). Also, fecal incontinence of different stages in 58 -72 % and obstructive defecation in 71 % were cured in total.

Conclusion

These results convincingly demonstrate that pelvic organ prolapse often can cause symptoms of overactive bladder (including urinary urgency incontinence and nocturia), obstructive micturition, fecal incontinence, pain, and obstructive defecation. According to the etiology and pathophysiology as described (1,2), and figure 1, a large number of these symptoms could be cured or improved in high percentages. The published original papers show that 2nd stage POP causes similar prevalences of these symptoms as 3.-4.-stage POP Also the cure rates in 2nd stage POP were similar to those in stages 3-4 POP.

It is important that urologists in routine clinical practice be aware that bladder, bowel, and pain symptoms (as in Tables 1&2) are potentially curable and to advise women with these conditions accordingly. Also important to mention that Stage 2 POP can only be detected under a full Valsalva vaginal examination. All surgical techniques of POP repair should be reviewed for symptom cure, which would only be possible if exact ligamentous repair is performed. As women in postmenopausal status and women with anterior POP have much higher anatomical and symptomatic recurrences, it was recommended that the use of some form of alloplastic material in these women needs to be reconsidered.9

Table 2. Surgical cure rates of symptoms of different pain, fecal incontinence,e and obstructive defecation in women with pelvic organ prolapse 2. – 4. Stage. Data from the Propel study (ClinicalTrials.gov-Identifier: NCT00638235).1,10,11

Written by: Bernhard Liedl,1 Mathias Barba,2 Maren Wenk3

- Urologische Klinik München-Planegg, Germany

- Urological Department, Kreiskrankenhaus Ebersberg, Germany

- Department of Urology, University Medical Center Mannheim, Germany

- Liedl B, Barba M, Wenk M. Pelvic floor reconstruction-update 2024: prolapse-associated symptoms and their treatment. Urologie. 2024.

- Petros P, Ulmsten U. An integral theory of female urinary incontinence. Experimental and clinical considerations. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1990;69:7-31.

- Petros P, Ulmsten U. Role of the pelvic floor in bladder neck opening and closure I: Muscle forces. Int Urogynecol J. 1997;8:74-80.

- Bush MB, Liedl B, Wagenlehner F, Petros P. A finite element model validates an external mechanism for opening the urethral tube prior to micturition in the female. World J Urol. 2015;33(8):1151-7.

- Liedl B, Goeschen K, Sutherland SE, Roovers JP, Yassouridis A. Can surgical reconstruction of vaginal and ligamentous laxity cure overactive bladder symptoms in women with pelvic organ prolapse? BJU Int. 2019;123(3):493-510.

- Himmler M, Rakhimbayeva A, Sutherland SE, Roovers JP, Yassouridis A, Liedl B. The impact of sacrospinous ligament fixation on pre-existing nocturia and co-existing pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(4):919-28.

- Petros P. Severe Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women May Be Caused By Ligamentous Laxity in the Posterior Fornix of the Vagina. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;36:351-4.

- Himmler M, Kohl M, Rakhimbayeva A, Witczak M, Yassouridis A, Liedl B. Symptoms of voiding dysfunction and other coexisting pelvic floor dysfunctions: the impact of transvaginal, mesh-augmented sacrospinous ligament fixation. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(10):2777-86.

- Shkarupa D, Zaytseva A, Kubin N, Kovalev G, Shapovalova E. Native tissue repair of cardinal/uterosacral ligaments cures overactive bladder and prolapse, but only in pre-menopausal women. Cent European J Urol. 2021;74(3):372-8.

- Liedl B, Goeschen K, Grigoryan N, Sutherland SE, Yassouridis A, Witczak M, Roovers J-P. The Association Between Pelvic Organ Prolapse, Pelvic Pain and Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery Using Transvaginal Mesh: A Secondary Analysis of a Prospective Multicenter Observational Cohort Trial. Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2020;9(4):79-95.

- Himmler M, Gottl K, Witczak M, Yassouridis A, Gold DM, Liedl B. The impact of transvaginal, mesh-augmented level one apical repair on anorectal dysfunction due to pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(11):3261-73.