In Canada, given the budgetary constraints of a publicly funded health care system, academic and tertiary care centers additionally face significant reductions in operating room (OR) access during specific periods in the year (mostly summer months and winter holidays). The OR hours available to robotic surgeons are limited, mainly due to reduced nursing and anesthesia staffing. Unfortunately, such a reduction in surgical output increases surgical wait times. Nevertheless, surgical delays' effect on the oncological prognosis is a controversial topic and remains a common concern during patient counseling.

In this study,1 we aimed to assess the impact of this summer operative reduction (30-50% OR reductions) on outcomes at our institution. After reviewing our prospectively maintained database of patients who underwent robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) for clinically localized PCa in the past decade, we evaluated the effect of surgical wait times on Gleason score upgrading, change in UCSF-CAPRA and CAPRA-S scores before and after surgery, and biochemical recurrence (BCR).

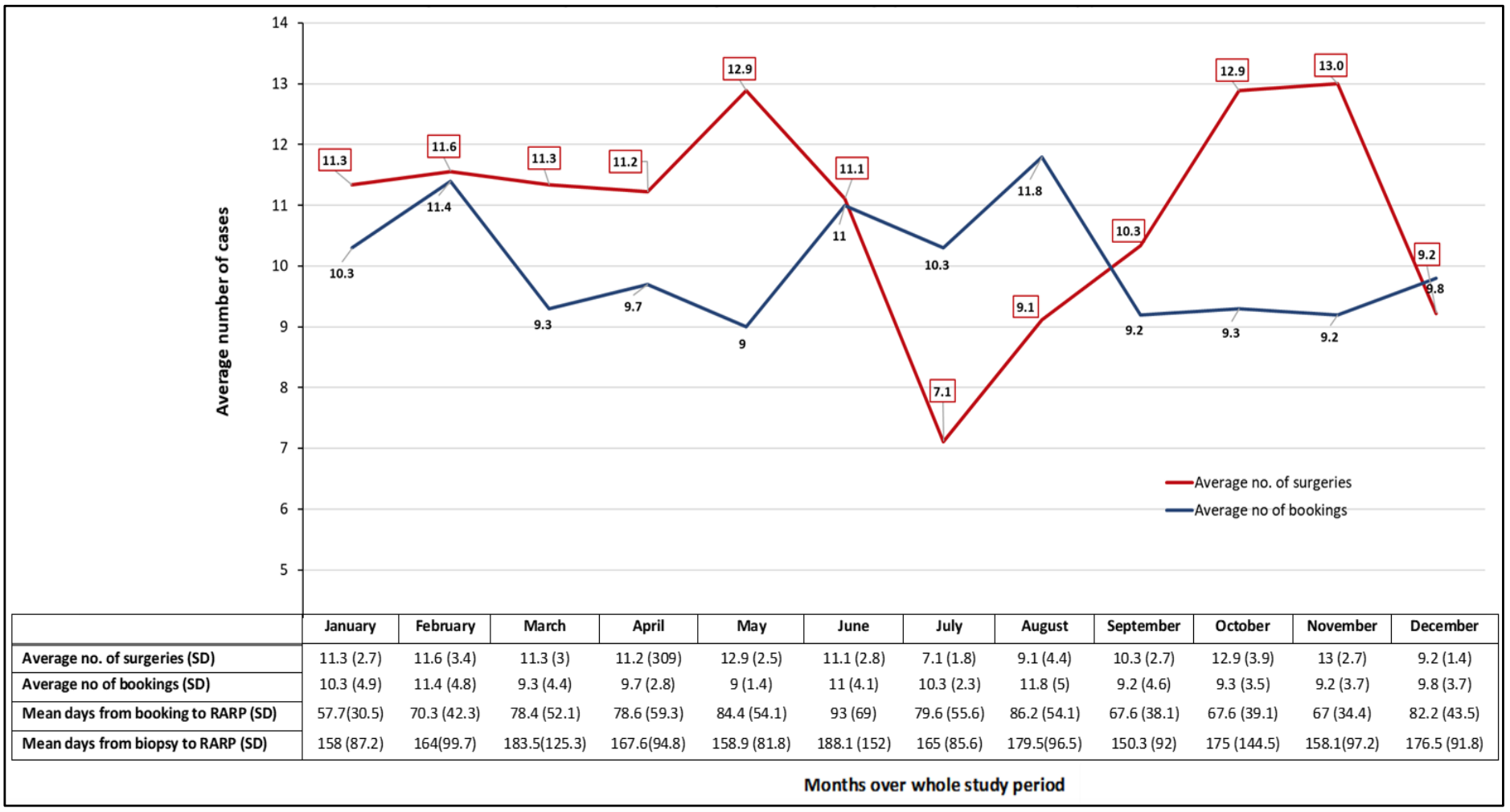

Our findings revealed that over a 10-year period, summer months consistently had the lowest surgical volumes despite above average booking volumes. The lowest surgical volume occurred during the month of July (mean of 7.1 cases), which was 35% less than the cohort average (see Figure 1). The below-average surgical monthly volumes were also consistently maintained in August. The longest average wait times occurred for patients booked for RARP in June (93 ± 69 days, p < 0.001)— the month prior to the summer OR cuts for July and August. Similarly, men who were booked for RARP surgery in the month of June also had the longest time from their initial biopsy to definitive RARP oncology surgery. On multivariable regression analyses, patients booked in June were significantly more at risk of experiencing an increase in CAPRA score [hazard ratio (HR) (95% confidence interval [CI]) 1.64 (1.02–2.63); p = 0.04] and in CAPRA risk group [HR (95% CI) 1.82 (1.04–3.19); p = 0.03]. Cohort analysis showed a moderate correlation between CAPRA-score difference and surgical wait time (Pearson correlation: r = − 0.062; p = 0.044).

Figure 1. Mean numbers (SD) of surgeries and bookings per months

As such, our study demonstrated consistent longer wait times during a decade of summer months. Although this finding did not predict worse post-RARP pathological outcomes, it was indirectly associated with a higher risk of BCR as represented by the difference between post-biopsy UCSF-CAPRA and post-surgical CAPRA-S scores. In this cohort, wait times between diagnosis and RARP were long (mean of 169 days). These findings highlight important care delivery gaps considering that the Canadian Surgical Wait Times initiative for urological cancers2 recommended a maximum wait time of 90, 60, and 28 days in low, intermediate, and high-risk PCa, respectively. It is worth mentioning that there seems to be an inconsistent number of average cases performed over a single year, especially between September and November after the summer months, where we observed a surge in the mean number of cases. At our academic center, two robots were at our disposal at two different sites which are unique and helps to compensate. Compensating for the surgical delays by increasing volumes in September–November may have prevented any significant negative impact on oncological outcomes in our cohort.

Overall, we believe that our findings have implications for policymakers seeking to ensure that surgical care is delivered in a timely fashion, especially in the current era of the COVID-19 pandemic with the subsequent anticipated delays where it is expected to have even longer surgical wait times. Also, our study may help increase public and patient awareness of the monthly/seasonal inconsistent surgical outputs. We believe that other compensatory mechanisms to sustain consistent yearly operative output should be considered, especially in those requiring cancer surgery.

Written by: Ahmed S. Zakaria, MD, MSc,1 David-Dan Nguyen, MPH,2 and Kevin C. Zorn, MD, FRCSC, FACS1

- Department of Surgery, Division of Urology, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM), Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- Zakaria, Ahmed S., Félix Couture, David-Dan Nguyen, Côme Tholomier, Hanna Shahine, Franziska Stolzenbach, Malek Meskawi, Pierre I. Karakiewicz, Assaad El-Hakim, and Kevin C. Zorn. "Impact of surgical wait times during summer months on the oncological outcomes following robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy: 10 years’ experience from a large Canadian academic center." World journal of urology (2020): 1-7.

- Canadian Surgical Wait Times (SWAT) Initiative. "Consensus document: recommendations for optimal surgical wait times for patients with urological malignancies." The Canadian journal of urology 13 (2006): 62.