While the possibilities are endless, if you didn’t think about social media, then you may not be considering where a significant portion of patients are getting at least some of their health information, particularly as usage continues to increase each year.1 In many ways, conversations about misinformation – how to identify it, where it’s found, and what impact it has – have become part of our daily discourse in a variety of different contexts, both within and outside of healthcare.

Approximately 8 out of 10 American adults seek health information online2 with 33% turning to YouTube and 20% turning to TikTok before consulting their doctors.3 Additionally, a recent survey found that nearly 1 in 5 American adults trust health influencers more than local medical professionals.4 Meanwhile, patients with prostate cancer who rely primarily on the internet for health information report more decisional regret and worse-than-expected treatment experiences.5 Given the wide-reaching dissemination of health information online, as well as the inequalities and disparities among racial/ethnic groups seen in prostate cancer screening,6 we analyzed and compared prostate cancer screening videos on YouTube and TikTok. More specifically, we focused on whether the videos represent racial and ethnic diversity, accurately reflect guidelines pertaining to high-risk cohorts, and meet validated quality criteria for consumer health information.

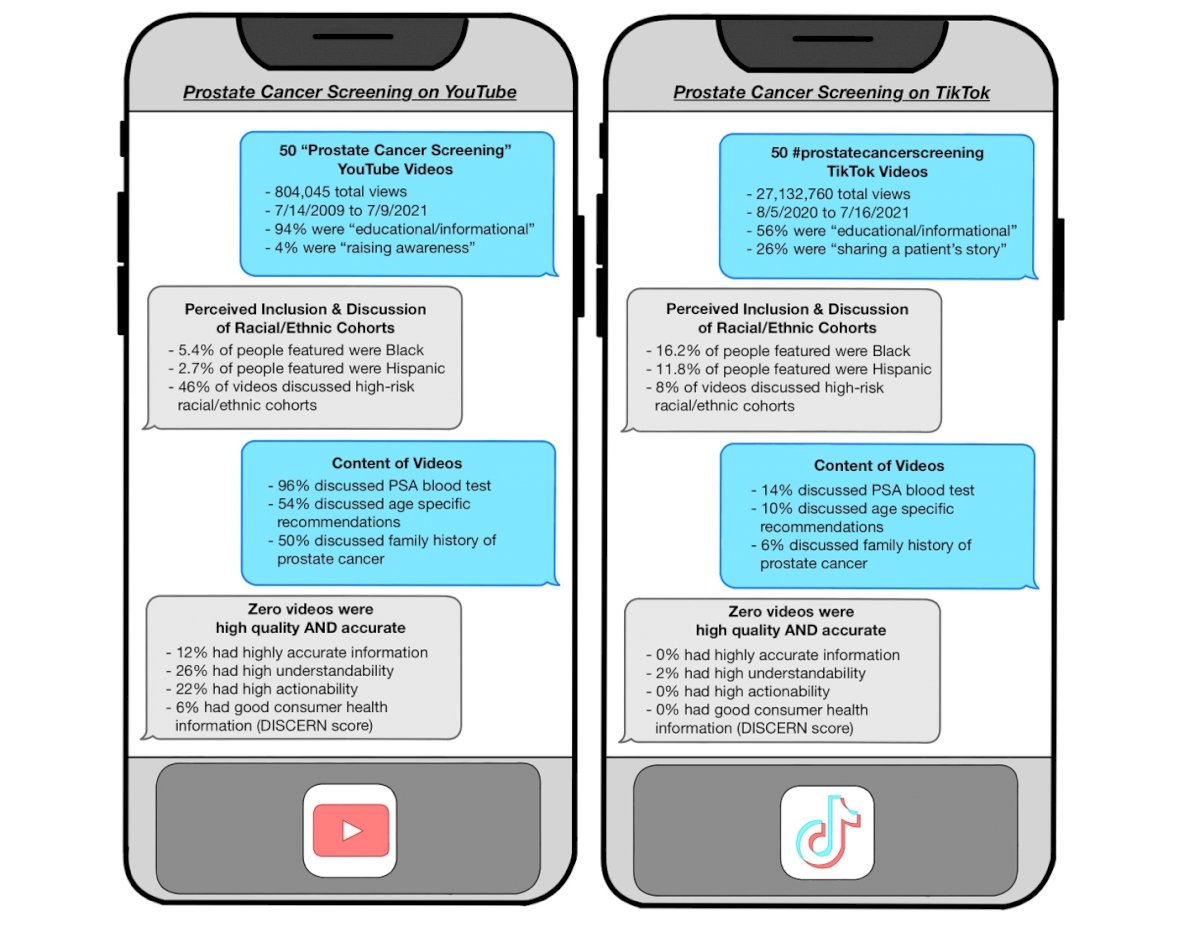

We found that among the top 50 videos on each platform, there were zero videos that contained both high-quality and accurate information, and both platforms lacked racial and ethnic diversity (Figure 1). When comparing the videos on each platform, YouTube videos were a higher quality overall, but they reached a significantly smaller audience and many were outdated due to being published prior to guideline changes. Additionally, YouTube videos were more likely to be either accurate or have specific characteristics associated with higher quality (i.e., being understandable and actionable). When we compared YouTube videos with racial/ethnic representation to videos without representation, we found no significant differences in terms of level of misinformation or quality of consumer health information. A similar analysis stratified by representation was not completed for the TikTok videos due to a lack of videos with sufficient “high-quality” metrics.

Figure 1. Summary of prostate cancer screening content on YouTube and TikTok. Note: PSA = prostate-specific antigen

Returning now to our initial scenario, we cannot ignore the fact that many patients seek health information from social media platforms like YouTube and TikTok. With regard to prostate cancer screening, these videos contribute to the dissemination of subpar information that may worsen the disparities seen in prostate cancer screening. Given this, we propose three proactive recommendations to our healthcare community. First, there should be a concerted effort to publish diverse, high-quality, and accurate information on these platforms. Second, we should amend or delete old videos as many of them become outdated as guidelines change, and we should report low quality or inaccurate videos to hosting platforms. Third, we should familiarize ourselves with trustworthy content creators that we can recommend to patients. Ultimately, healthcare providers cannot single-handedly curb misinformation on social media, but it is critical to be cognizant of it in order to limit the negative impact and maximize the positive impact that it’s capable of having on patients and their medical care.

Written by: Max Abramson1 & Kara L. Watts, MD2

- Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

- Department of Urology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY

References:

- Social Media Fact Sheet. Website. Pew Research Center. Updated 04/07/2021. Accessed 11/10/2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/?menuItem=2fc5fff9-9899-4317-b786-9e0b60934bcf

- Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. P T. Jul 2014;39(7):491-520.

- Levine AS. Doctors And Nurses Are Becoming Internet Stars. Some Are Losing Their Jobs Over It. Forbes. 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexandralevine/2022/12/20/healthcare-influencers-medical-creators-firing/?sh=208940a13eef&utm_source=ForbesMainTwitter&utm_campaign=socialflowForbesMainTwitter&utm_medium=social

- CharityRXNews. The Shifting Role of Influence and Authority in the Rx Drug & Health Supplement Market. CharityRx. 2022. https://www.charityrx.com/blog/the-shifting-role-of-influence-and-authority-in-the-rx-drug-health-supplement-market

- Shaverdian N, Kishan AU, Veruttipong D, et al. Impact of the Primary Information Source Used for Decision Making on Treatment Perceptions and Regret in Prostate Cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. Sep 2018;41(9):898-904. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000387

- Pietro GD, Chornokur G, Kumar NB, Davis C, Park JY. Racial Differences in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Prostate Cancer. Int Neurourol J. Nov 2016;20(Suppl 2):S112-119. doi:10.5213/inj.1632722.361