While SABR has become a well-established option for low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer, its safety and efficacy in high-risk disease is not yet fully understood. The FASTR trial was designed to assess the tolerability of SABR in patients who were anticipated to have poor tolerance to standard therapy. Patients were enrolled on this trial between 2011 and 2015 if they had at least 1 high-risk feature as per NCCN criteria, no evidence of metastatic disease on conventional imaging, and either a score of ≥3 on the Vulnerable Elderly Scale or if they declined standard therapy. Patients were treated with 40 Gy to the prostate and 25 Gy to the pelvic lymph nodes in 5 once-weekly fractions over 5 weeks. They also received 12 months of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). However, FASTR was terminated early to due to excessive genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity at 6 months.1

Owing to the high rates of acute toxicity in FASTR, FASTR-2 was designed with several protocol modifications to minimize toxicity. Patients were treated with a lower dose of 35 Gy to the prostate, pelvic nodal irradiation was omitted, and stricter dose constraints for the bladder and rectum were used. ADT was also extended to 18 months. Patients were enrolled between 2015 and 2017, and at 1 year, the toxicity profile in FASTR-2 was much more favourable.2

To better characterize the long-term toxicity and clinical outcomes of SABR in high-risk prostate cancer, we sought to update the results from the FASTR and FASTR-2 trials via a retrospective study. Toxicities were graded according to CTCAE version 4.03 per the original trial protocols, and relevant outcomes of interest were collected.

A total of 44 patients were eligible for analysis, 16 from FASTR and 28 from FASTR-2. Most patients were over 70 years old (77%). High-risk features included clinical T3-T4 disease (27%), Gleason score ≥8 (46%), and baseline PSA >20 (50%). Median follow-up for the entire cohort was 6.4 years. Radiation doses to the prostate, bladder, and rectum were significantly lower in FASTR-2 compared to FASTR.

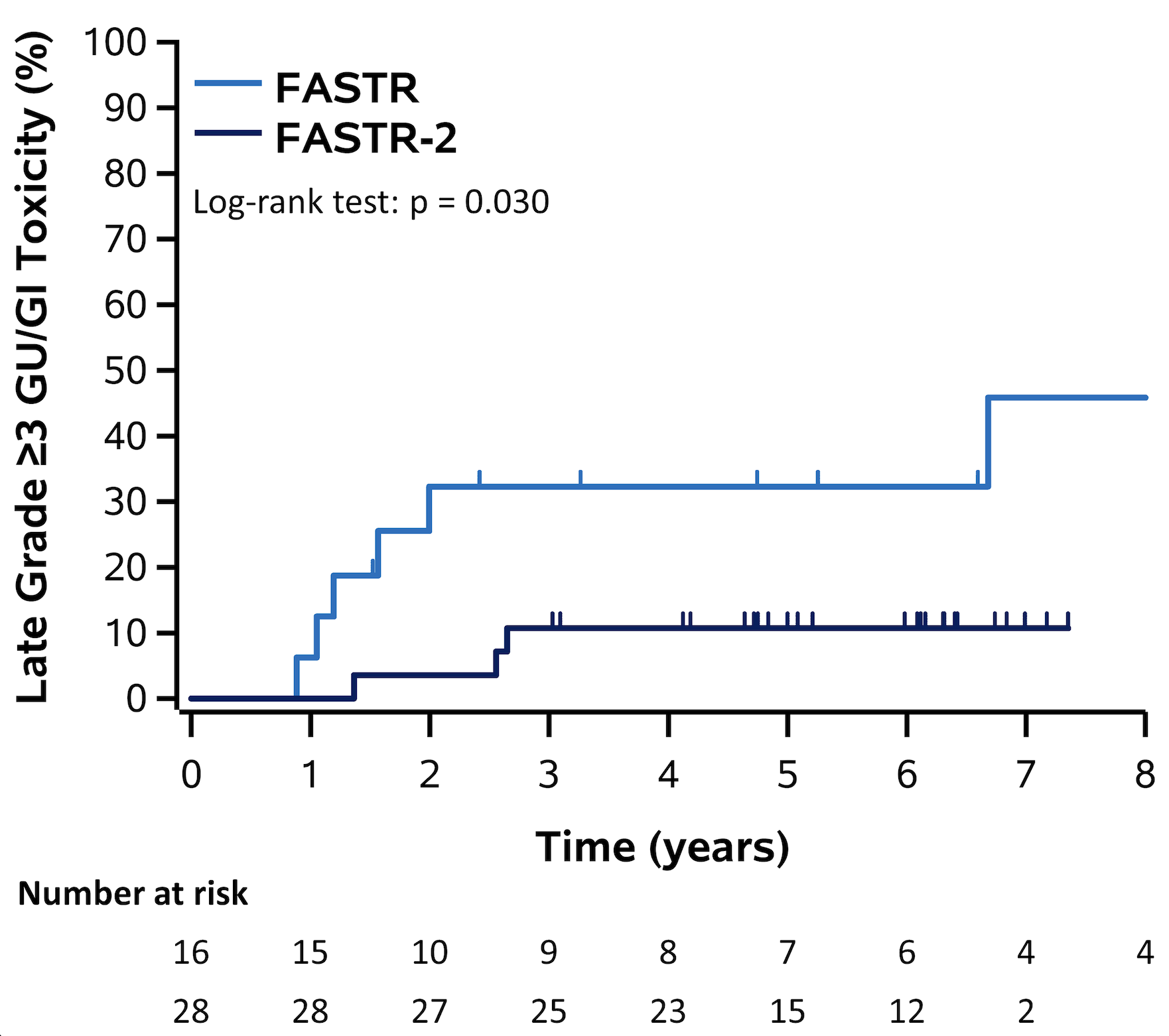

The cumulative incidence of late grade ≥3 GU/GI adverse events was significantly higher in FASTR compared to FASTR-2 (p=0.03), with a 5-year estimate of 32.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 14.8–61.2) in FASTR and 10.7% (95% CI 3.6–29.6) in FASTR-2. Prior analyses suggest the driver of GI toxicity in FASTR was driven by rectal OAR doses from the prostate treatment rather than bowel exposure from the nodal treatment.3 The toxicity in FASTR-2 was largely comparable to other prostate SABR studies, likely a result of the more conservative total dose and rectal dose volume constraints used.

Figure 1: Cumulative incidence of late grade ≥3 genitourinary (GU)/gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity in FASTR and FASTR-2.

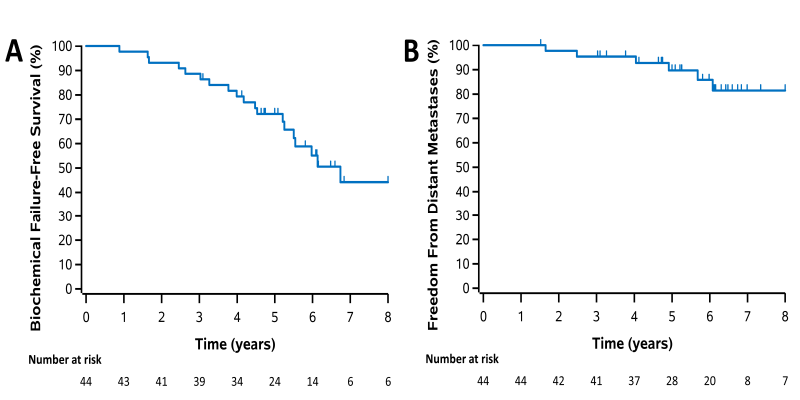

In terms of clinical outcomes, the 5-year biochemical failure-free survival was 72.1% (95% CI 56.2–83.1), and freedom from distant metastases was 89.7% (95% CI 74.6–96.0). Overall, these outcomes were largely comparable to other studies of prostate SABR as well as to more standard radiotherapy regimens in high-risk disease.4

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier plots for all patients for (a) biochemical failure-free survival, (b) freedom from distant metastases.

The long-term results from FASTR and FASTR-2 indicate that SABR can be safely delivered in high-risk prostate cancer as long as careful consideration is given to dose and technical delivery and our results are in line with other reported series.4 It also appears to be a reasonable alternative to standard radiotherapy regimens, particularly for patients who desire a more convenient treatment option. Our experience with FASTR and FASTR2 emphasizes the importance of deploying new radiation treatment approaches in the context of prospective trials and larger prospective, randomized trials are still required to validate this treatment approach in high-risk disease. Incorporation of advanced molecular imaging, such as PSMA PET and MRI may also provide additional opportunities for individualized SBRT delivery for high-risk patients.5

Written by: Terence Tang, MD, George Rodrigues, MD, PhD, Andrew Warner, MSc, & Glenn Bauman, MD

Division of Radiation Oncology, Department of Oncology, Western University and London Regional Cancer Program, London, Ontario, Canada

References:

- Bauman G, Ferguson M, Lock M, Chen J, Ahmad B, Venkatesan VM, et al. A phase 1/2 trial of brief androgen suppression and stereotactic radiation therapy (FASTR) for high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015 Jul 15;92(4):856-62.

- Callan L, Bauman G, Chen J, Lock M, Sexton T, D'Souza D, et al. A phase I/II trial of fairly brief androgen suppression and stereotactic radiation therapy for high-risk prostate cancer (FASTR-2): preliminary results and toxicity analysis. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2019 Jul 16;4(4):668-673.

- Bauman G, Chen J, Rodrigues G, Davidson M, Warner A, Loblaw A. Extreme hypofractionation for high-risk prostate cancer: Dosimetric correlations with rectal bleeding. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7:e457-e462.

- van Dams R, Jiang NY, Fuller DB, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for high-risk localized carcinoma of the prostate (SHARP) consortium: Analysis of 344 prospectively treated patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110:731-737.

- Liu W, Loblaw A, Laidley D, et al. Imaging biomarkers in prostate stereotactic body radiotherapy: A review and clinical trial protocol. Front Oncol. 2022;12:863848.