Older adults with mPC experience a high incidence of treatment-related toxicities such as pain, fatigue, and psychological distress.2 Frail older adults (who have loss of physiologic reserves with age-related declines in various domains like cognition and physical health) with mPC are even more vulnerable to these toxicities.3 However, the older adult population (age 65 and older) is often underrepresented in clinical trials, resulting in limited evidence available to determine optimal supportive care interventions.4

Furthermore, poor management of these symptoms often leads to reduced quality of life and early treatment discontinuation.3 Hence, there is a need to understand the specific symptoms and the severity of symptoms faced by this demographic, so that effective supportive care interventions can be developed and implemented to improve treatment outcomes. Timing of measurement is also important; if a symptom occurs early on after starting a medication, is moderate to severe for several days, then resolves, it is likely still clinically important to patients but may not be reported at the next check-in 3-4 weeks later due to recall bias and focus on current symptoms. In addition, time pressures in clinic may not be conducive to detailed exploration of symptoms. Through daily symptom monitoring of older adults receiving mPC treatments, we sought to understand the treatment toxicities they face throughout a treatment cycle.

Ninety participants completed the study (mean age: 77 years, chemotherapy (n= 34), ARAT (n=43), radium 223 (n=13), of which 42% were frail as identified through the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13). All participants reported treatment toxicities using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale daily during their first treatment cycle (3-4 weeks). Symptoms scored 4 or higher out of 10 were categorized as moderate to severe. The study's objectives were to identify the most common moderate to severe symptoms, their duration, and the differences in these results by frailty. The proportion of participants with improved symptom severity after baseline was also explored.

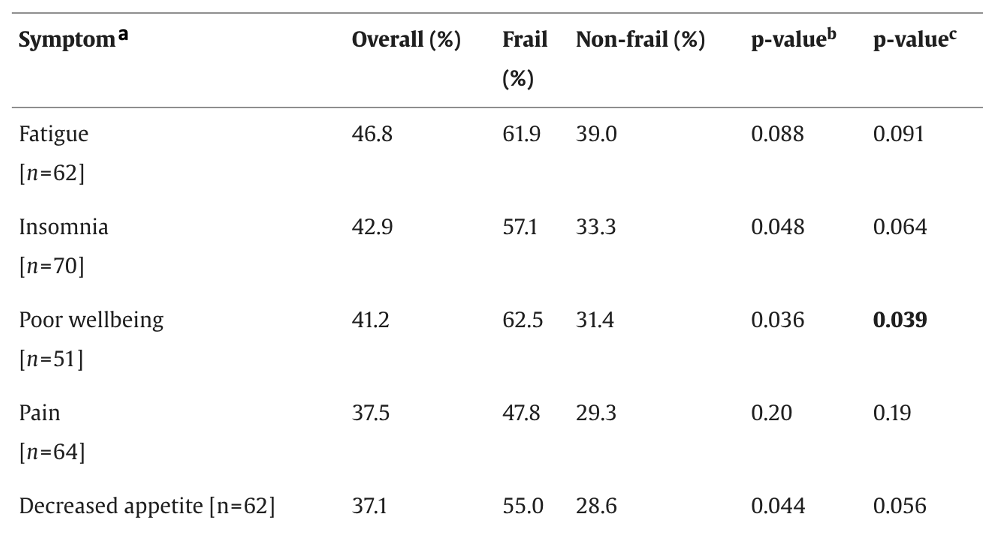

The most common symptoms reported were fatigue (46.8%), insomnia (46.8%), poor well-being (41.2%), pain (37.5%) and decreased appetite (37.1%). Frail older adults experienced a higher incidence of these symptoms compared to those who were non-frail (see Table 1), but only differences in well-being were statistically significant (p = 0.039).

Frail older adults also experienced pain and insomnia (median of 4.0 and 2.0 days, respectively) twice as long as non-frail older adults (median of 2.0 and 1.0 days, respectively). Interestingly, even though frail adults had a higher incidence of decreased appetite (46.8% in frail vs 31.4% in non-frail), non-frail participants experienced them for a greater duration (median of 4 days in frail vs median of 6 days in non-frail). However, these differences in duration were not statistically significant.

Importantly, while participants receiving chemotherapy showed statistically significant improvements in areas like well-being, pain, and fatigue, participants receiving ARAT and radium 223 did not. This may be because patients receiving chemotherapy tend to be more symptomatic at the onset of treatment compared to those starting an ARAT or radium 223.

Many previous clinical trials have identified fatigue as the most common treatment-related symptom while other toxicities are not commonly reported.5,6,7,8 However, our study identified other symptoms that are prevalent in this demographic but are often unnoticed or overlooked. Our approach of monitoring symptoms daily reduces recall bias and allows for real-time understanding of toxicities that older adults with mPC face during treatment.

Overall, the study explored short-term treatment toxicities in older adults with mPC and highlighted the impact of frailty on symptom experiences. Frail participants had a higher incidence of all symptoms (Table 1), and symptoms like pain and insomnia lasted longer in those who were frail. Some limitations of the study were non-random assignment to treatment, lack of a control group, a small sample size (n = 90), and relatively few participants in the radium 223 group. Long-term patterns of toxicity are also unclear as participants were followed for their first treatment cycle only. The findings of this study highlight the need for further research with a larger sample size and longer follow-up to refine our understanding of toxicity profiles of older adults with mPC and the impact of frailty. This will enable the development of effective supportive care interventions for older adults with mPC.

Table 1. Incidence of Moderate to Severe Symptoms by Frailty

Note: Patients who had moderate-to-severe symptoms at baseline were removed. b = p-value before adjusting for the treatment group. c = p-value after adjusting for the treatment group.

Written by: Ferozah Nasiri, Kian Godhwani, Milothy Parthipan, MScPT, & Shabbir M. H. Alibhai, MD, MSc

Department of Medicine, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada

References:

- Parthipan M, Feng G, Breunis H, et al. Understanding the incidence, duration, and severity of symptoms through daily symptom monitoring among frail and non-frail older patients receiving metastatic prostate cancer treatments. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2024;15(3):101720-101720.

- Zylla DM, Gilmore GE, Steele GL, et al. Collection of electronic patient-reported symptoms in patients with advanced cancer using Epic MyChart surveys. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2019;28(7):3153-3163.

- Ethun CG, Bilen MA, Jani AB, Maithel SK, Ogan K, Master VA. Frailty and cancer: Implications for oncology surgery, medical oncology, and radiation oncology. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67(5):362-377.

- Rostoft S. Frailty in Cancer Patients. Springer eBooks. Published online January 1, 2020:433-439.

- Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Alpha Emitter Radium-223 and Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(3):213-223.

- Evans CP, Higano CS, Keane TE, et al. The PREVAIL Study: Primary Outcomes by Site and Extent of Baseline Disease for Enzalutamide-treated Men with Chemotherapy-naïve Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. European Urology. 2016;70(4):675-683.

- Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in Metastatic Prostate Cancer without Previous Chemotherapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(2):138-148.

- Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus Prednisone or Mitoxantrone plus Prednisone for Advanced Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(15):1502-1512.