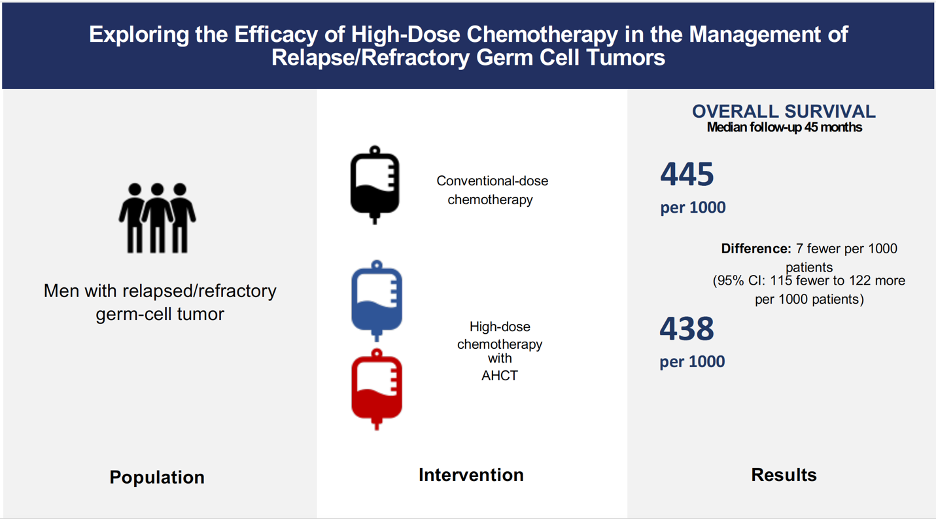

The IT94 trial enrolled 280 participants, 263 of whom had data available for OS analysis. This study compared VIP/VeIP for four cycles with VIP/VeIP for 3 cycles, followed by one cycle of CarboPEC with AHCT. IT94 study excluded patients with refractory disease.3 Based on data provided by this study, we concluded that HDCT followed by AHCT may have little to no effect on OS in relapsed GCT patients (HR 0.98, 95%CI 0.68 to 1.42; p=0.916; very low-certainty evidence; Fig.1).

Figure 1. Anticipated absolute OS effects (95%CI)

No information was provided about secondary outcomes, such as quality of life (QoL), progression-free survival (PFS), and chronic toxicities. Data from Pico´s study were utilized to produce the main conclusions about event-free survival (EFS), response rate, and acute toxicities. However, we conducted additional exploratory analysis using data from the included non-randomized studies.1,2

Based on the IT94 trial,3 we determined that HDCT followed by AHCT may improve EFS of men with relapsed GCTs (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.10; p=0.169; 263 participants; low-certainty evidence).

247 out of 280 participants had data available for response rate analysis. We did not find significant differences in overall response rate (RR 1.03, 95%CI 0.84 to 1.26; p=0.775; low-certainty evidence) and failure (RR 0.96, 95%CI 0.71 to 1.30; p=0.775; low-certainty evidence) comparing HDCT followed by AHCT with CDCT. Exploring the impact of data from included no-randomized trials on overall response rate and failure, we found no evidence that HDCT followed by AHCT improves complete response or decreases failure.

For acute toxicity G3, 274 out of 280 participants had data accessible for analysis; we concluded that HDCT followed by AHCT likely increases the risk of developing febrile neutropenia and thrombocytopenia and may result in a significant increase in nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and mucositis. Exploring the influence of data from included no-randomized trials on febrile neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, we found that our conclusions did not change much.

Finally, we also found that HDCT followed by AHCT may increase death due to toxicity (RR: 2.22, 95%CI 0.70 to 7.03; p=0.176; low-certainty evidence).

The conclusion about the primary outcome was supported by very-low certainty evidence; hence, it should be interpreted cautiously. All secondary outcomes were exploratory and, therefore, are only hypothesis-generating.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

1. Primary outcome

We identified four studies that met the predefined inclusion criteria: two randomized and two non-randomized prospective controlled trials. Regarding OS, we only had data from IT94, Mardiak´s, and Faure-Conter´s studies.1-3

The IT94 trial excluded patients with refractory disease. Therefore, we are unable to draw conclusions for males with refractoriness to first-line platinum-containing chemotherapy. Pico´s trial used CDCT and HDCT regimens that are infrequently utilized in the current clinical practice.4 In addition, the experimental arm only included one cycle of HDCT followed by AHCT. A practice that is hardly used in high-volume academic cancer centers.5,6 Thus, the results of the international TIGER trial are highly expected.7 This trial recruited people with relapsed and refractory GCTs. Moreover, it evaluates the effects of chemotherapy regimens frequently used in this clinical scenario (i.e. TI-CE followed by AHCT versus TIP) and can identify patients who benefit the most from HDCT followed by AHCT based on IPFSG risk classification.

There was insufficient data to analyze pre-specified subgroup analysis of histological subtype, IPFSG prognostic score, type of CDCT protocol, type of HDCT protocol, and number of cycles of HDCT. Besides, we could not undertake a meta-analysis of overall survival due to the lack of reliable data from included non-randomized studies.

2. Secondary outcomes

Regrettably, data were unavailable for all secondary outcomes of interest (i.e. QoL, PFS, and chronic toxicities). Consequently, we cannot draw conclusions respecting these outcomes, which are essential for decision-making.

EFS, response rate, and acute toxicities data were mainly available for people with relapsed GCT. We further explored the results of these outcomes using data provided by Mardiak´s1 and Faure-Conter´s2 studies. As a result, we performed meta-analyses of response rates and acute hematological toxicities. Secondary outcomes were exploratory; thus, they should be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, differences in acute toxicities and death due to toxicity are consistent with what we see in daily clinical practice.

Consequently, the findings of this review are not strong enough to support or discourage the utilization of HDCT followed by AHCT in patients with relapsed or refractory GCTs.

Quality of the evidence

The certainty of evidence for OS was very low due to study limitations and imprecision. Despite this, the IT94 trial is the best available evidence comparing the efficacy of HDCT followed by AHCT with CDCT in males with relapsed GCTs.

The certainty of evidence supported secondary outcomes such as EFS, response rate, acute gastrointestinal toxicity, and death due to toxicity was rated as low due to trial limitations and imprecision. On the contrary, we rated the certainty of evidence for neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia as moderate due to study limitations.

Despite the fact that we included two non-randomized prospective controlled trials in our systematic review, data from these studies were not utilized to build the main conclusions. According to the ROBINS-I tool, the risk of bias in Mardiak´s and Faure-Conter´s studies was considered critical. Additionally, Mardiak´s1 trial had a small sample size (n=25), included people with treatment-naïve germ cell tumor (n=9), and did not provide sufficient data to calculate time to event outcomes for relapsed/refractory germ cell tumor population. Faure-Conter´s2 trial also had a small sample size (n=19) and included male and female infants (n=9) as well as participants with ovarian and sacrococcygeal primary sites.

In view of the very-low-certainty evidence supporting overall survival, the current body of evidence does not allow a definitive conclusion.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Compared with previous reviews, ours was focused on summarizing the best available evidence and addressing outcomes such as QoL and toxicities.

The use of HDCT with AHCT in relapsed/refractory germ cell tumors is primarily based on phase I and II trials and retrospective studies. The only available phase III randomized controlled trial (the IT94 study), which compared CDCT with HDCT followed by AHCT, failed to show a significant survival benefit from HDCT. Despite several limitations, this trial remains the best available prospective evidence regarding the utilization of HDCT in this unique group of patients.

Several systematic and literature reviews have been published on this topic so far. Systematic reviews have shown results that are in keeping with our findings. For instance, Husnain et al. failed to show any significant results for overall survival in patients with relapsed/refractory germ cell tumors treated with HDCT with AHCT.8 Petrelli and colleagues found comparable efficacy when CDCT and HDCT were used as salvage therapies in relapsed/refractory germ cell tumors.9 Additionally, Bin Riaz et al. established that a single cycle of HDCT with AHCT does not improve survival compared with CDCT.10

General implications

This review revealed a lack of high-quality prospective research in relapsed/refractory germ cell tumor population. On the other hand, IT94 and TIGER trials show that it is possible to conduct phase III RCTs in a rare patient population.

Design

It is well known that randomized controlled trials are the best way to assess the efficacy and safety of an intervention. The highly expected TIGER trial is a phase III randomized controlled study comparing CDCT using TIP with HDCT using TI-CE as first-salvage chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory germ cell tumors. Due to obvious reasons, this could not be a double-blind trial. Nonetheless, we expect that outcome assessors are blinded to interventions, mainly to assess subjective outcomes. We recommend avoiding early stopping analysis and deviations from the intended intervention as much as possible because they may bias results.

Additionally, we suggest exploring heterogeneity using covariates pre-specified in the protocol. If authors decide to perform post hoc analyses, we encourage them to use covariates with strong biological rationale. As for statistical analyses, we recommend using interaction tests to evaluate subgroups and considering multiple testing corrections if multiple comparisons are made. Finally, this trial should avoid crossover, given that it may obscure the real impact of HDCT on overall survival.

Endpoints

Cancer patients want two things: to live longer and to live well. Therefore, randomized controlled trials must be able to assess quality of life. TIGER trial would not evaluate this outcome as per ClinicalTrials.gov, which would be disappointing, considering we are trying to cure young people with the potential to live a long life. For the same reason, it is also important to determine long-term toxicities associated with HDCT.

Written by: Juan Briones-Carvajal, MD, MSc, Oncología Médica UC, Profesor Asistente, Centro de Cáncer UC, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Diagonal Paraguay 319, Santiago, Chile.

References:

- Mardiak J, Fuchsberger P, Lakota J, et al. Sequential intermediate high-dose therapy with etoposide, ifosfamide and cisplatin for patients with germ cell tumors. Neoplasma. 2000;47(4):239-243.

- Faure-Conter C, Orbach D, Cropet C, et al. Salvage therapy for refractory or recurrent pediatric germ cell tumors: the French SFCE experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(2):253-259.

- Pico JL, Rosti G, Kramar A, et al. A randomised trial of high-dose chemotherapy in the salvage treatment of patients failing first-line platinum chemotherapy for advanced germ cell tumours. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(7):1152-1159.

- Al-Ezzi EM, Zahralliyali A, Hansen AR, et al. The Use of Salvage Chemotherapy for Patients with Relapsed Testicular Germ Cell Tumor (GCT) in Canada: A National Survey. Current Oncology. 2023;30(7):6166-6176.

- Feldman DR, Sheinfeld J, Bajorin DF, et al. TI-CE high-dose chemotherapy for patients with previously treated germ cell tumors: results and prognostic factor analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):1706-1713.

- Adra N, Abonour R, Althouse SK, Albany C, Hanna NH, Einhorn LH. High-Dose Chemotherapy and Autologous Peripheral-Blood Stem-Cell Transplantation for Relapsed Metastatic Germ Cell Tumors: The Indiana University Experience. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(10):1096-1102.

- NCT02375204. Standard-Dose Combination Chemotherapy or High-Dose Combination Chemotherapy and Stem Cell Transplant in Treating Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Germ Cell Tumors. In. Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Y, National Cancer I, European Organisation for R, et al., trans2015.

- Husnain M, Riaz IB, Kamal MU, et al. High Dose Chemotherapy with Autologous Stem Cell Transplant in Treatment of Germ Cell Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Blood. 2016;128(22):5829-5829.

- Petrelli F, Coinu A, Rosti G, Pedrazzoli P, Barni S. Salvage treatment for testicular cancer with standard- or high-dose chemotherapy: a systematic review of 59 studies. Med Oncol. 2017;34(8):133.

- Bin Riaz I, Umar M, Zahid U, et al. Role of one, two and three doses of high-dose chemotherapy with autologous transplantation in the treatment of high-risk or relapsed testicular cancer: a systematic review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(10):1242-1254.