While teratoma is generally believed to be less aggressive and less likely to relapse,1 existing evidence from single-center and retrospective studies have indicated that primary testicular NSGCT containing teratomatous elements are linked to poorer oncological outcomes.2–6

Because of these concerning features, most guidelines have extrapolated the rationale derived from metastatic teratoma to patients with clinical stage I (CSI) teratoma and recommend retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND), even in men without imaging evidence of retroperitoneal nodal enlargement.7–11 The NCCN 2024 guideline, updated its recommendations and now it recommends RPLND for patients with teratoma and somatic malignant transformation (SMT), and either RPLND or surveillance to those with CSI pure teratoma as shown below:

We aimed to evaluate the long-term oncological outcomes of patients with CSI pure teratoma compared to other patients with CSI NSGCT in one of the largest surveillance cohorts.

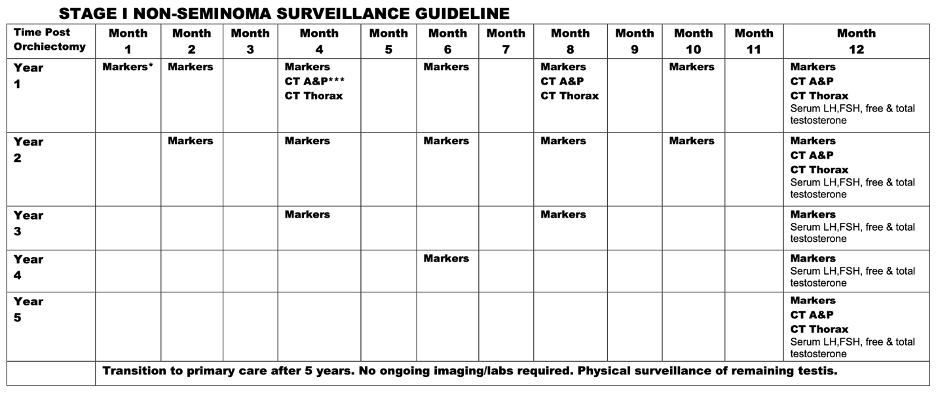

In our prospectively maintained cohort, after orchiectomy, all patients were closely monitored according to our institutional protocols. These protocols have evolved over the years but generally entail tumor markers every 2 months for 2 years, every 4 months in year 3, every 6 months in year 4, and annually in year 5, with computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis every 4 months for the first year, then at year 2 and year 5 as illustrated below:

Patients were grouped, into three groups:

- CS I pure teratoma / somatic malignant transformation (SMT) or both

- CSI NSGCTs

- CSI NSGCTs with teratomatous elements

In our statistical analysis RFS, CSS, and OS rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method. Log-rank test was used to assess the impact of pure teratoma vs. any other histology in the primary pathology. For the cumulative incidence of relapse, we included the relapsed patients as the event of interest and those patients who died of other causes as a competing risk, and for reporting the cumulative incidence of relapse, we used Grey’s method.

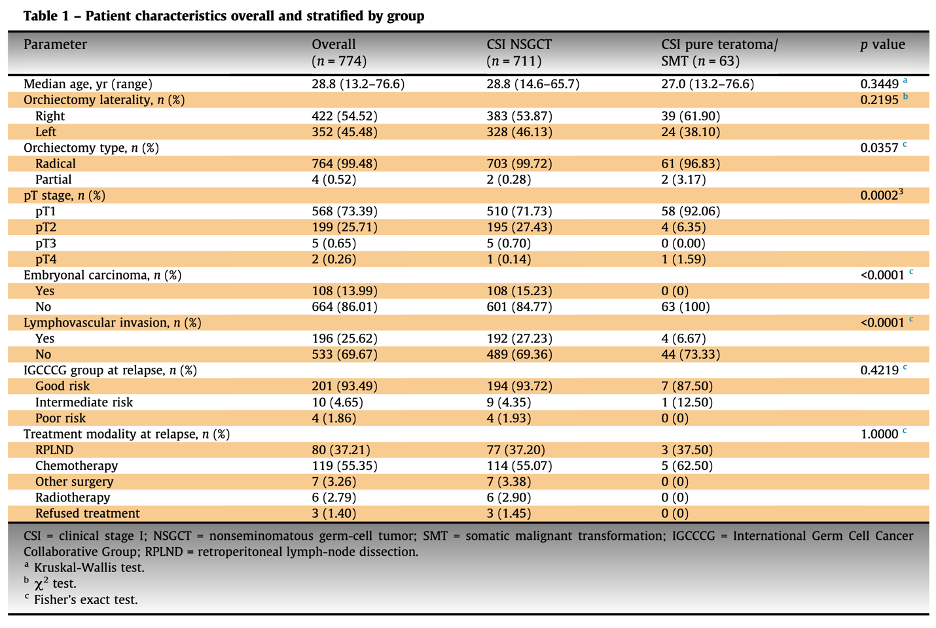

In our active surveillance cohort, we identified 774 patients with clinical stage I non-seminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs). Among these, 63 patients (8%) had pure teratoma, and three (4.7%) exhibited evidence of transformation to another histology within the primary testicular tumor. The baseline characteristics were generally similar between the teratoma group and the other NSGCTs, with a few notable exceptions. The teratoma group had a higher rate of partial orchiectomy (3.2% vs. 0.3%, p=0.04), a lower incidence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) (6.7% vs. 27.2%, p<0.0001), and a higher proportion of pT1 stage tumors (92.06% vs. 71.73%, p=0.0002), as shown in the table below.

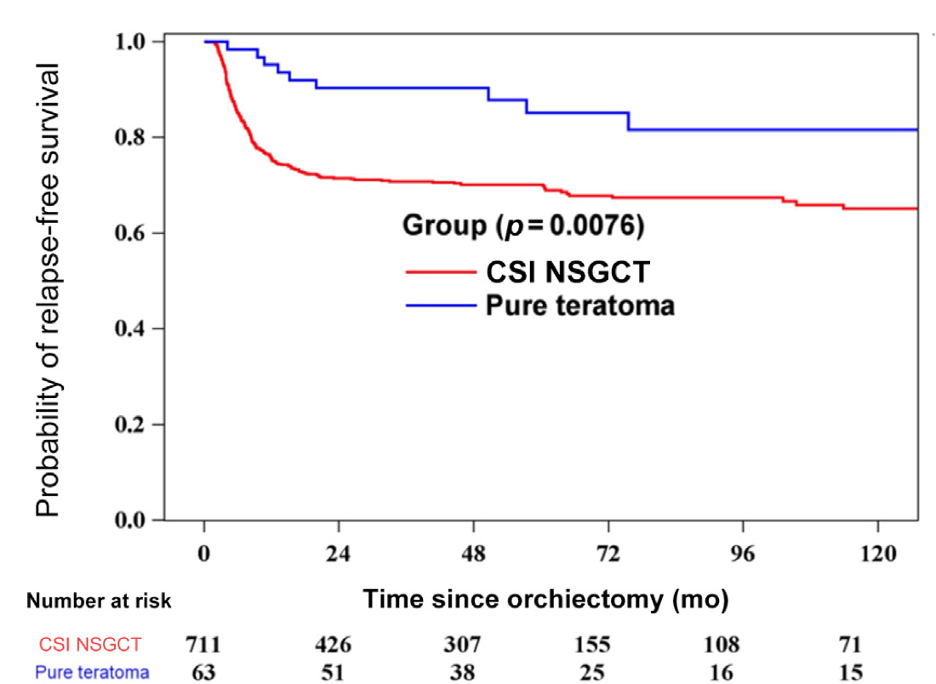

In our primary endpoint analysis, with a median follow-up of 61 months (IQR 32.9-102.6), we found that 52 patients (82.5%) with pure teratoma remained relapse-free, compared to 493 patients (69.3%) with NSGCT. The pure teratoma group exhibited a superior 6-year relapse-free survival (RFS) rate of 85.2% (95% CI [72.0-92.5]) versus 67.8% (95% CI [63.8-71.4]) for the NSGCT group (p=0.0076).

Notably, the treatment at relapse among the pure teratoma group was similar to that of the other NSGCTs:

- The majority of patients in both groups received chemotherapy (62.5% in the teratoma group vs. 55.1% in the NSGCT group)

- Over a third of the patients underwent primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) (37.5% in the teratoma group vs. 37.2% in the NSGCT group).

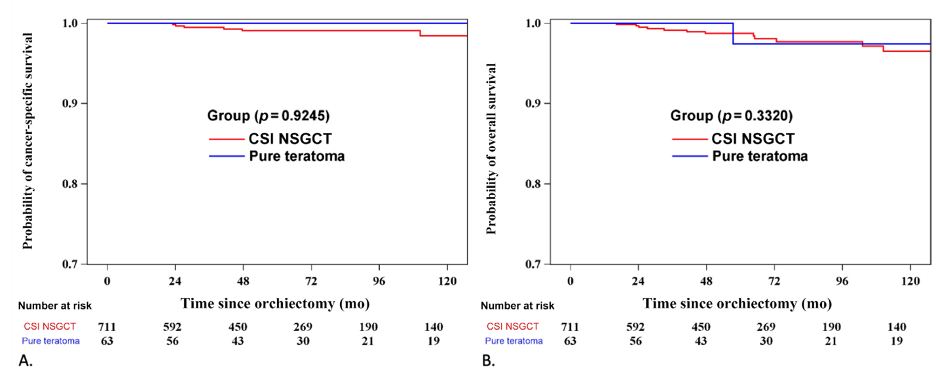

Regarding the CSS and OS analysis, at the time of data analysis, 97.4% of patients were alive, and 2.65% had died, with only 8 deaths (1%) attributable to testicular cancer or its treatment. Both CSS and OS were similar between the teratoma group and the NSGCT group. The 6-year CSS was 100% for the teratoma group compared to 99.1% for the NSGCT group (p=0.93). The 6-year OS was 97.4% for the teratoma group and 98.1% for the NSGCT group (p=0.33).

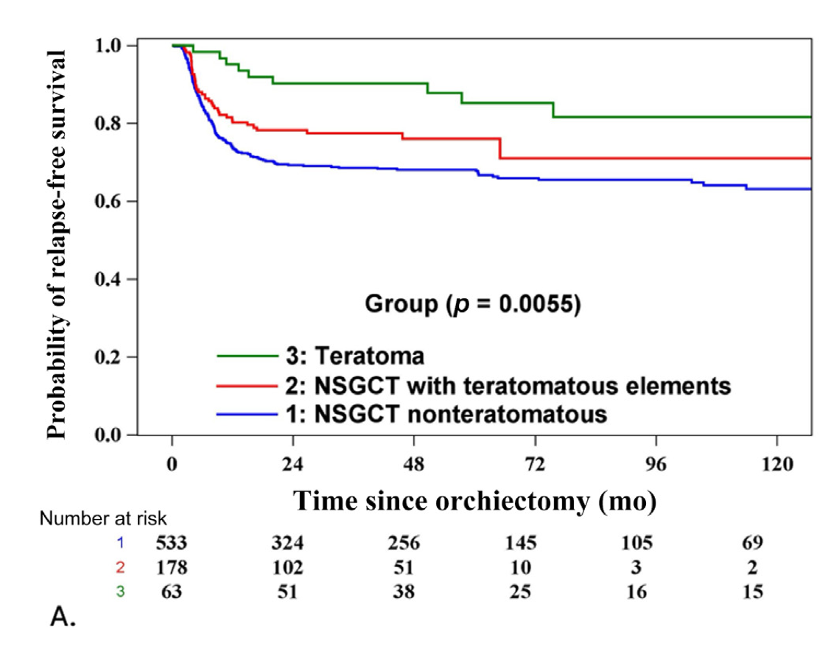

Our exploratory analysis comparing the three pre-defined different groups found that the 6-year RFS was highest for the pure teratoma (85.2% vs. 71.0% vs. 66.0%) vs, the NSGCT with teratomatous elements group and the NSGCT group, respectively. This difference was found to be significant (p=0.0055).

To the best of our knowledge,ge this is the largest study of patients with CSI pure teratoma managed on surveillance. Our findings revealed that patients with CS I pure teratoma exhibited a significantly better RFS compared to CS I NSGCTs. While a greater proportion of the teratoma relapses treated with chemotherapy required post-chemotherapy surgery, there was no difference in CSS or OS which attests to the safety of this approach.

Written by:

- Julian Chavarriaga MD, Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Canada; Department of Urology, Cancer Treatment and Research Centre, Luis Carlos Sarmiento Angulo Foundation, Bogota, Colombia

- Robert J Hamilton MD, MPH, FRCSC, Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Canada

- Herr HW, LaQuaglia MP: MANAGEMENT OF TERATOMA. Urol Clin N Am 20:145–152, 1993

- Inci K, Dogan HS, Akdogan B, et al: Presence of teratoma in orchiectomy specimen increases the need for postchemotherapy RPLND. Urologic Oncol Seminars Orig Investigations 29:38–42, 2011

- Beck SDW, Foster RS, Bihrle R, et al: Teratoma in the Orchiectomy Specimen and Volume of Metastasis are Predictors of Retroperitoneal Teratoma in Post-Chemotherapy Nonseminomatous Testis Cancer. J Urology 168:1402–1404, 2002

- Paffenholz P, Nestler T, Maatoug Y, et al: Teratomatous Elements in Orchiectomy Specimens Are Associated with a Reduced Relapse-Free Survival in Metastasized Testicular Germ Cell Tumors. Urol Int 106:1061–1067, 2022

- Funt SA, Patil S, Feldman DR, et al: Impact of Teratoma on the Cumulative Incidence of Disease-Related Death in Patients With Advanced Germ Cell Tumors. J Clin Oncol 37:2329–2337, 2019

- Rabbani F, Farivar-Mohseni H, Leon A, et al: Clinical outcome after retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy of patients with pure testicular teratoma. Urology 62:1092–1096, 2003

- Stephenson A, Eggener SE, Bass EB, et al: Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Stage Testicular Cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urology 202:272–281, 2019

- Stephenson A, Bass EB, Bixler BR, et al: Diagnosis and Treatment of Early-Stage Testicular Cancer: AUA Guideline Amendment 2023. J Urol 211:20–25, 2024

- Gilligan T: Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Guideline Testicular Cancer V.1.2024. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2024. All rights reserved. Accessed [September 19, 2024]. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org.

- Nicol D: Testicular Cancer Guideline. ISBN 978-94-92671-23-3. EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, the Netherlands, 2024.

- Patrikidou A, Cazzaniga W, Berney D, et al: European Association of Urology Guidelines on Testicular Cancer: 2023 Update. Eur Urol 84:289–301, 2023