(UroToday.com) The Society of Nuclear Medicine & Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) 2024 Annual Meeting held in Toronto, ON between June 8th and June 11th, 2024 was host to a prostate cancer therapy session. Dr. Meryam Losee presented the results of a study evaluating the effect of bone marrow disease on hematologic toxicity and PSA response to 177Lu-PSMA-617 therapy.

In the phase 3 VISION trial, all outcome endpoints favored 177LuPSMA-617 (LuPSMA) + standard of care (SOC) compared to SOC alone, leading to LuPSMA approval for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).1,2 Beyond clinical trial-defined eligibility criteria, Dr. Losee noted that it remains challenging to identify those patients most likely to benefit from or experience adverse events (AEs) from newly approved drugs. In VISION, ~50% of men in the LuPSMA arm did not have a PSA50 response, and ~47% had hematologic AEs. Furthermore, patients with a“superscan” bone scan were excluded, but the amount of bone disease on PSMA-PET/CT was not considered.

There is evidence from retrospective studies that patients with diffuse bone involvement on PSMA-PET/CT have a PSA50 response rate of 58% with grade 3–4 hematologic adverse events occurring in 8-22% of patients,3 and patients who have a total tumor SUVmean >10 exhibit a better response to LuPSMA.4 This study aimed to evaluate if the extent and heterogeneity of bone disease on PSMA-PET/CT was associated with hematologic AEs and PSA50 response. The study investigators hypothesized that a higher percentage of bone disease with a corresponding lower SUV of 3-10 would predict more hematologic toxicity with a lower PSA50 responses, compared to those with a higher percentage of bone disease with an SUV >10.

Dr. Losee and colleagues queried an IRB-approved prospectively maintained registry to evaluate all mCRPC patients who received standard-of-care LuPSMA at their institution between June 2022 and July 2023. All met VISION criteria with ≥1 PSMA-avid lesion (uptake > liver) to be eligible for standard-of-care LuPSMA.

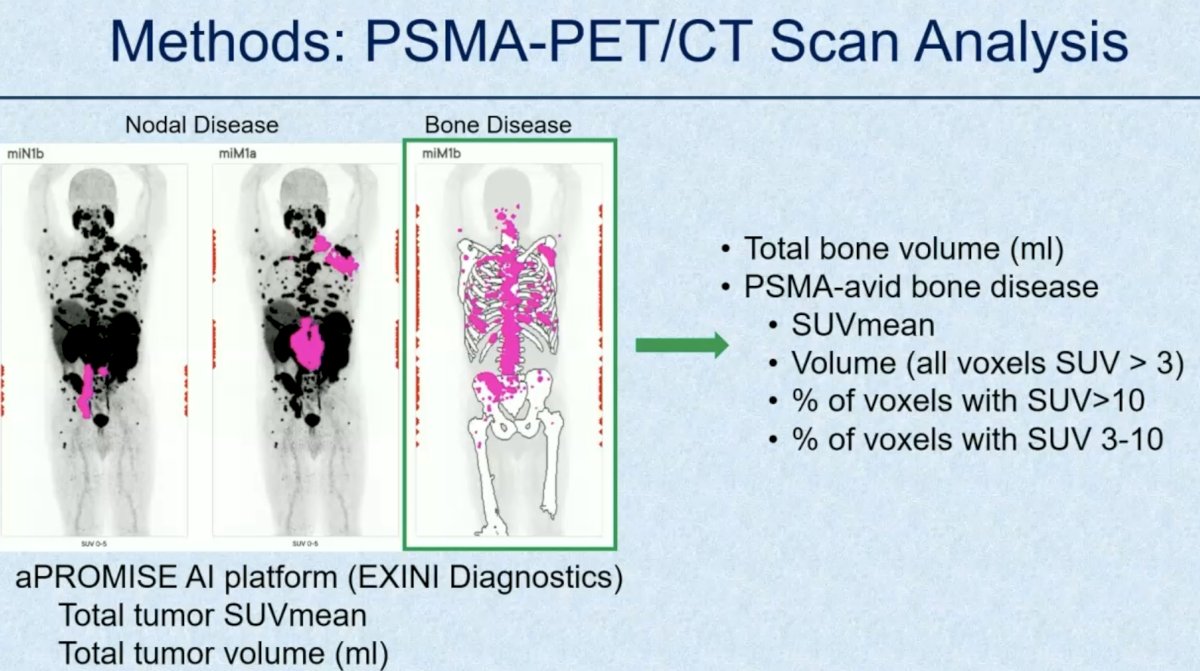

Pre-therapy PSMA-PET/CT scans were analyzed for disease burden using the aPROMISE platform (EXINI Diagnostics). The following data were extracted:

- Total tumor SUVmean

- Total bone volume

- Total volume of PSMA-avid disease in the bone (voxel SUV > 3)

- Percentage of bone disease with SUV > 10

- Percentage of bone disease with SUV 3-10.

Clinical data was extracted from the registry and medical record, including dose delays, dose reductions or discontinuations due to hematologic AEs, the reason for stopping LuPSMA, and PSA levels during treatment. PSA50 response was defined as ≥50% decline in PSA level at any time during LuPSMA therapy. The Wilcoxon rank sum and Fisher exact tests were used to perform univariable comparisons.

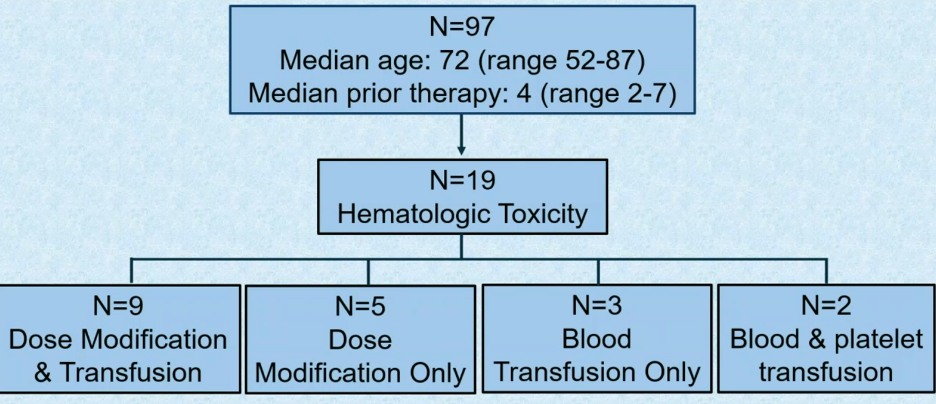

Ninety-seven men (mean age 72 +/- 8 years) received ≥1 cycle of LuPSMA (median: 4 cycles, range: 1–6). Nineteen patients experienced hematologic toxicity.

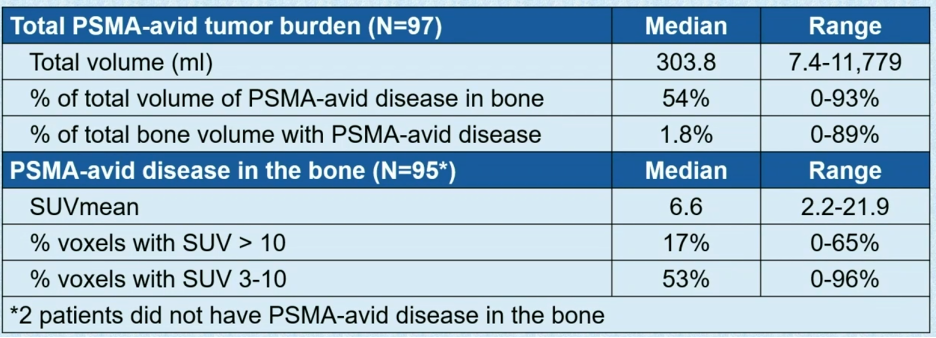

Of the 95 patients with PSMA-avid bone disease, the median percentage of total bone volume with PSMA-avid disease was 1.9%. The median percentage of voxels with bone disease SUV >10 and 3–10 was 17% and 53%, respectively.

Patients with a higher percentage of PSMA-avid bone disease in the total bone volume (=voxel SUV > 3) were more likely to require dose delays or reductions (p<0.001) or dose discontinuation (p=0.006) due to hematologic AEs, compared to those with a lower percentage.

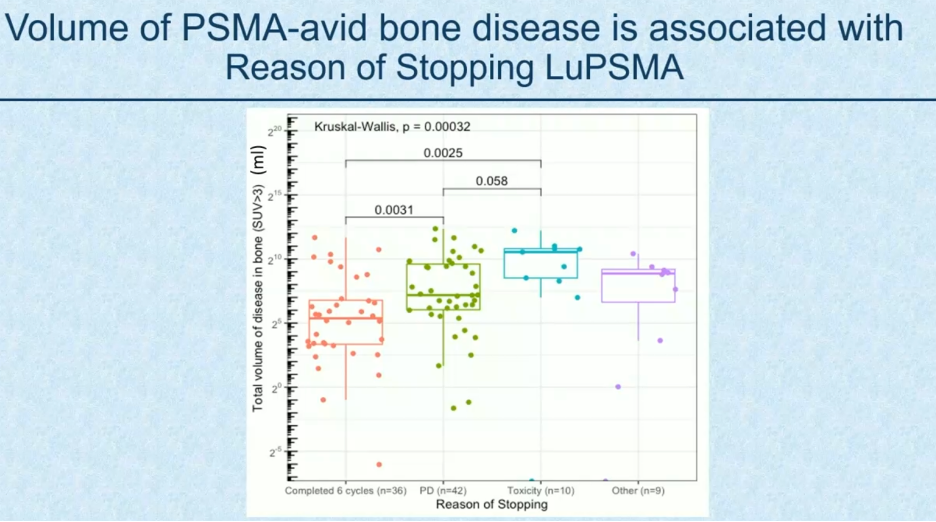

No significant associations were found between heterogeneity of PSMA uptake in bone disease (percent of voxels with SUV > 10 vs. 3-10) and hematologic AEs. The reason for stopping treatment was completion of all planned 6 cycles (n=36), progressive disease (n=42), toxicity (n=10), and other (n=9). Compared to patients who completed 6 cycles of LuPSMA, a higher volume of bone disease was observed for those who stopped LuPSMA for toxicity (p=0.0025) or progressive disease (p=0.0031).

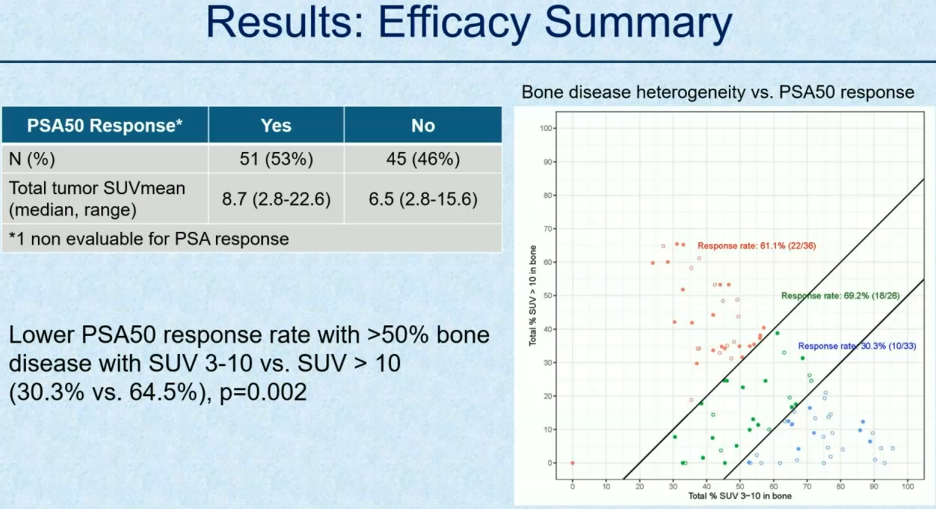

The overall PSA50 response rate was 53% (n=51). Of the 96 evaluable patients for PSA50 response, those with a much higher proportion of bone disease with SUV 3-10, compared to SUV>10, had a significantly lower PSA50 response rate (30.3% vs. 64.5%, p=0.002). PSA50 responders were more likely to have a higher total tumor SUVmean (median 8.7, range 2.8-22.6) versus PSA-50 non-responders (median 6.5, range 2.8-15.6, p=0.01).

Dr. Losee concluded that this data validates total tumor SUVmean as a predictor of PSA50 response. Both total volume and heterogeneity of PSMA-avid bone disease appear to be associated with the likelihood of PSA50 response. A higher percentage of PSMA-avid bone disease was associated with hematologic AEs and the reason for stopping LuPSMA. These findings may be helpful to guide clinical decision-making around dosing of LuPSMA therapy in routine practice and to select patients for clinical trials.

Presented by: Meryam Losee, BS, George Washington School of Medicine, Washington, DC.

Written by: Rashid Sayyid, MD, MSc – Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Clinical Fellow at The University of Toronto, @rksayyid on Twitter during the Society of Nuclear Medicine & Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) 2024 Annual Meeting held in Toronto, ON between June 8th and June 11th, 2024

References:

- Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN, et al. Lutetium-177–PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1901-1103

- FDA approves Pluvicto for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-pluvicto-metastatic-castration-resistant-prostate-cancer. Accessed on June 9, 2024.

- Gafita A, Fendler WP, Hui W, et al. Efficacy and Safety of 177Lu-labeled Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Radionuclide Treatment in Patients with Diffuse Bone Marrow Involvement: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Eur Urol. 2020;78(2): 48-54.

- Buteau JP, Martin AJ, Emmett L, et al. PSMA and FDG-PET as predictive and prognostic biomarkers in patients given [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): a biomarker analysis from a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(11): 1389-97.