(UroToday.com) The 2024 Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) held in Lugano, Switzerland between April 25th and 27th was host to PSMA for Diagnostic and Treatment session. Dr. Thomas Hope discussed how to select patients for radioligand therapy in clinical practice, discussing patient eligibility criteria and how to determine the appropriate number of cycles to administer.

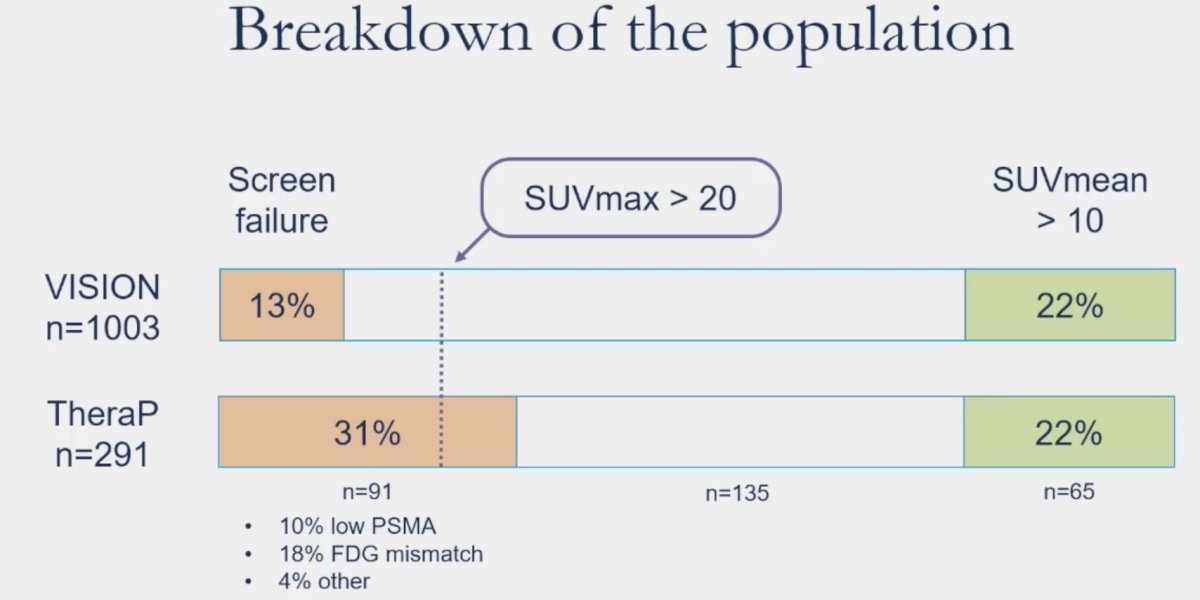

What were the PET imaging-based inclusion criteria for patients in the VISION and TheraP trials? In VISION, patients were required to have PSMA-positive disease on the basis of a central review of 68Ga-PSMA-11 staging scans. PSMA positivity was defined as uptake greater in metastatic lesions than in the liver. Further, they could have no PSMA-negative metastatic lesions. 13% of screened men were deemed trial ineligible based on these criteria. A PSA50 response (i.e., ≥50% decrease in PSA levels) was noted in 46% of radionuclide-treated patients.1 To screen into TheraP, all men had both 68Ga-PSMA-11 and 18F-FDG PET/CT and were required to have high PSMA-expression (at least one site with SUVmax≥20) and no sites of FDG-positive/PSMA-negative disease. 31% of screened men were deemed trial ineligible, and the PSA50 response was higher at 65% in this more ‘strictly’ selected cohort of patients.2 Thus, we see early evidence that treatment selection based on imaging parameters/criteria may influence treatment response/sensitivity to radionuclide therapy.

Do baseline PSMA PET imaging parameters predict treatment response? An ad hoc analysis of VISION demonstrated that event-free and overall survivals were superior among patients with higher mean standardized uptake values (SUV) at baseline. This is critical for appropriate patient selection, whereby Lu-PSMA should be encouraged for eligible patients with high mean SUV values (e.g. ≥10), whereas those with limited uptake may be considered for alternate regimens (e.g,, cabazitaxel as in the control arm of TheraP).

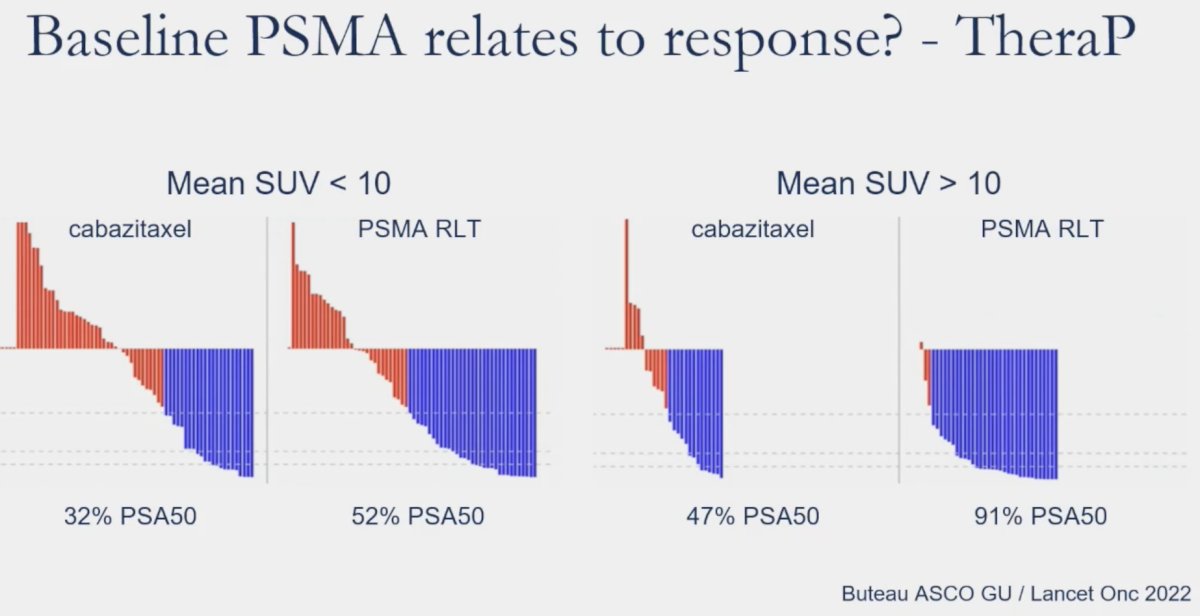

A similar ad hoc analysis was conducted in TheraP. In patients with PSMA SUVmean levels of ≥10, the odds of a response to LuPSMA were substantially higher (odds ratio [OR]: 12.2, 95% CI 3.4 – 59.0) as compared to those with PSMA SUVmean of <10 (OR: 2.2, 95% CI 1.1 – 4.5) (p-value for difference = 0.03). This was reflected in superior PSA50 response rates (91% versus 52%) and PSA progression-free survival HRs (0.45 versus 0.77) for SUVmean ≥ 10 versus SUVmean < 10.

As illustrated below, there is a higher proportion of men who were screened trial ineligible in the TheraP trial (31% versus 13%). As such, this suggests that some VISION trial participants would have likely screened ineligible for TheraP.

What happens to these patients in the “VISION-TheraP” gap? Analysis of the UCSF cohort (n=99) suggest that 39% of these patients achieve a PSA50 response.3

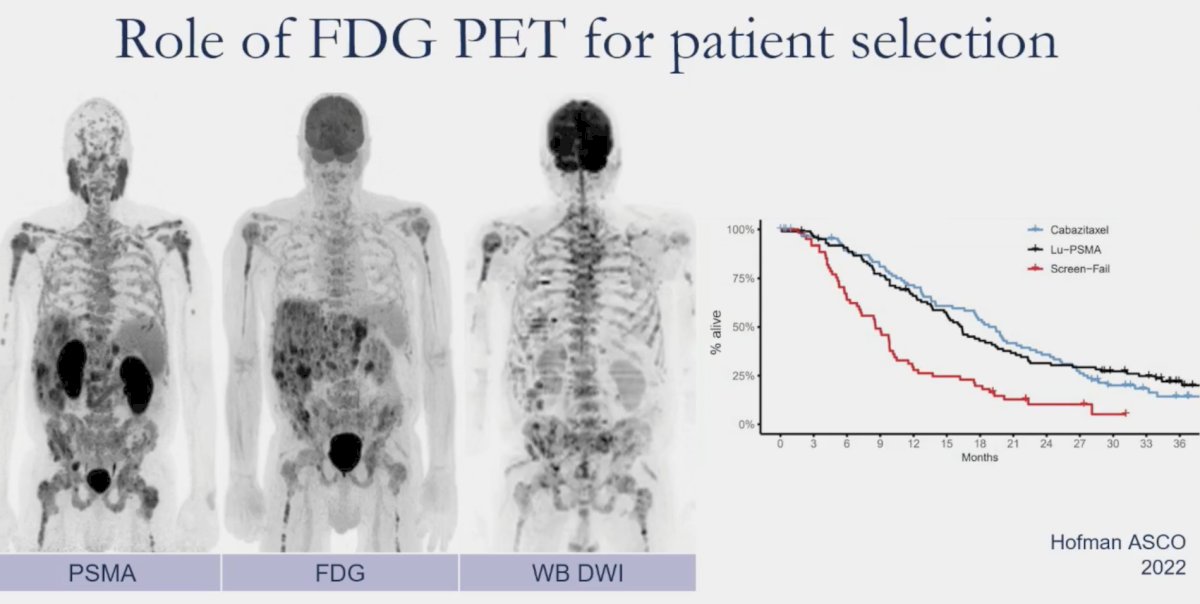

What is the role of FDG PET for patient selection? Ad hoc analysis of TheraP has demonstrated that metabolic tumor volume on FDG-PET was a prognostic biomarker, with volume ≥200mL portending significantly worse treatment response rates with both LuPSMA and cabazitaxel.

But do we need FDG PETs performed for patients being considered for PSMA radioligand therapy or is PSMA alone sufficient? In an analysis of 89 mCRPC men referred for 177Lu-PSMA therapy between 2019 and 2021, Seifert et al. demonstrated that FDG PET – PSMA discordances occur in 18% of patients. However, only 5% of patients had mismatch findings not detected using PSMA PET-only.4 As such, perhaps FDG PET is not required for screening potentially eligible patients for radioligand therapy. Patients for PSMA radioligand therapy should be selected based on uptake greater than that in the liver. SUVmean > 10 is not relevant for clinical decision-making in the current patient population.

How do we determine when to delay or stop treatment? This is likely a multifactorial decision related to patient response (PSA and imaging), patient symptoms, and toxicities (mostly hematologic).

With regards to the assessment of patient response in Lu-PSMA-treated patients, John et al. have demonstrated that post-treatment SPECT changes in tumor volume correlate with overall survival.

Additionally, combining post-treatment SPECT changes with PSA kinetics can be used to dictate dosing and potentially spare early responders additional therapy, and thus toxicity. In a cohort of 125 men treated with 6-weekly 177LuPSMA-I&T, a composite PSA and 177Lu-SPECT/CT imaging response following the 2nd dose was used to determine ongoing management. Patients in response group 1 (marked reduction in PSA/imaging partial response) received a treatment break until subsequent PSA rise, at which time they were re-treated. Response group 2 (stable or reduced PSA and/or imaging stable disease) received 6-weekly treatments until six doses, or no longer clinically benefitting. Response group 3 patients (rise in PSA and/or imaging progressive disease) were recommended for an alternative treatment. Overall survival rates were 19.2 months, 13.2 months), and 11.2 months, respectively, confirming the safety of this approach in response group 1 patients. Notably, the median months of 'treatment holiday' for response group 1 was 6.1 months.6

What is the impact of post-treatment imaging on management? It appears that 28% of patients have radioligand therapy stopped due to disease progression. Conversely, 20% of patients have radioligand therapy stopped due to a marked response.

Dr. Hope noted that repeat imaging (preferably with post-treatment SPECT) should be performed to evaluate PSMA uptake. Conventional imaging (CT/MRI) is still needed to exclude the development of PSMA-negative disease.

Dr. Hope concluded his presentation with the following take-home messages:

- PSMA radioligand therapy should be reserved for patients with lesions demonstrating PSMA tracer uptake greater than that observed in the liver.

- PSMA SUVmean and nomograms should not be used to determine if a patient is a candidate for PSMA radioligand therapy. FDG PET should be saved for difficult circumstances.

- Post-treatment SPECT should be used to follow patients over time to evaluate for a response.

Presented By: Thomas Hope, MD, Professor, Department of Radiology, University of California, San Francisco, CA

Written by: Rashid Sayyid, MD, MSc - Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Clinical Fellow at The University of Toronto, @rksayyid on Twitter during the 2024 Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference, Lugano, Switzerland, April 25th - April 27th, 2024

References:

- Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 16;385(12):1091-1103.

- Hofman MS, Emmett L, Sandhu S, et al. [(177)Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): A randomized, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021 Feb 27;397(10276):797-804.

- Tuchayi AM, Yadav S, Jiang F, et al. Real-World Experience with 177Lu-PSMA-617 Radioligand Therapy After Food and Drug Administration Approval. J Nucl Med. 2024.

- Seifert R, Telli T, Hadaschik B, et al. Is 18F-FDG PET Needed to Assess 177Lu-PSMA Therapy Eligibility? A VISION-like, Single-Center Analysis. J Nucl Med. 2023;64(5): 731-7.

- John JR, Oommen R, Hephzibah J, et al. Validation of Deauville Score for Response Evaluation in Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Indian J Nucl Med. 2023;38(1): 16-22.

- Emmett L, John N, Pathmanandavel S, et al. Patient outcomes following a response biomarker-guided approach to treatment using 177Lu-PSMA-I&T in men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (Re-SPECT). Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2023; :15:17588359231156392. .

Gillessen, S. et al. (2024) ‘Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer. report from the 2024 Advanced prostate cancer consensus conference (APCCC)’, European Urology [Preprint]. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2024.09.017.