Bladder cancer treatment has evolved from traditional surgery and chemotherapy to include immunotherapy, targeted therapies, and antibody drug conjugates. These therapeutic innovations, along with advances in surgical techniques and multimodal approaches, continue to reshape clinical practice and improve outcomes for bladder cancer patients. However, the high cost of these treatments poses a significant challenge in low-income countries such as Morocco.

ll. IMMUNOTHERAPY IN NON-METASTATIC BLADDER CANCER

Neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy (NAC) with radical cystectomy (RC) improves overall survival (OS) versus RC alone and has been the recommended treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) for the past 40 years.1 Perioperative immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) could improve long-term clinical outcomes by priming anti-tumor immunity before surgery and eradicating micrometastatic disease.

Numerous phase II studies are showing promising activity of neoadjuvant immunotherapy with complete pathologic response rates (pT0 ~ 30-45%).

1. Neoadjuvant Setting

a. Durvalumab = NIAGARA Trial

Durvalumab is a selective, high-affinity, human IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody that binds to programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and blocks the interaction of PD-L1 with programmed death 1 and CD80. The phase III NIAGARA trial was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of perioperative durvalumab in combination with neoadjuvant gemcitabine–cisplatin followed by radical cystectomy, as compared with neoadjuvant gemcitabine–cisplatin followed by radical cystectomy alone, in cisplatin-eligible patients with MIBC. Event-free survival was one of two primary endpoints.

Overall survival was the key secondary endpoint.2

The estimated event-free survival at 24 months was 67.8% (95% CI, 63.6 to 71.7) in the durvalumab group and 59.8% (95% CI, 55.4 to 64.0) in the comparison group (95% CI, 0.56 to 0.82; p<0.001). The estimated overall survival (OS) at 24 months was 82.2% (95% CI, 78.7 to 85.2) in the durvalumab group and 75.2% (95% CI, 71.3 to 78.8) in the comparison group (95% CI, 0.59 to 0.93; p=0.01).

A pathological complete response occurred in 37.3% (95% CI, 33.2 to 41.6) of the patients in the durvalumab group and in 27.5% (95% CI, 23.8 to 31.6) of those in the comparison group (risk ratio, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.60). NIAGARA supports perioperative durvalumab with NAC as a potential new standard treatment for patients with cisplatin-eligible MIBC.

b. Pembrolizumab = PURE-01 Trial

The PURE-01 trial of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab prior to RC initially pioneered the use of neoadjuvant ICI in patients with MIBC.3 Both cisplatin eligible and ineligible patients were included.

The 36-month event-free survival (EFS) and OS were 74.4% [95% CI, 67.8-81.7] and 83.8% (95% CI, 77.8-90.2) in the ITT population, respectively. Within the cohort of patients who did not receive additional chemotherapy (N = 125), the 36-month RFS was 96.3% (95% CI, 91.6-100) for achieving ypT0N0, 96.1% (95% CI, 89-100) for ypT1/a/isN0, 74.9% (95% CI, 60.2-93) for ypT2-4N0, and 58.3% (95% CI, 36.2-94.1) for ypTanyN1-3 pathologic responses. EFS was significantly stratified among PD-L1 tertiles (lower tertile: 59.7% vs. medium tertile: 76.7% vs. higher tertile: 89.8%, P = 0.0013). PURE-01 results further confirm the sustained efficacy of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab before RC. PD-L1 expression was the strongest predictor of sustained response post-RC.

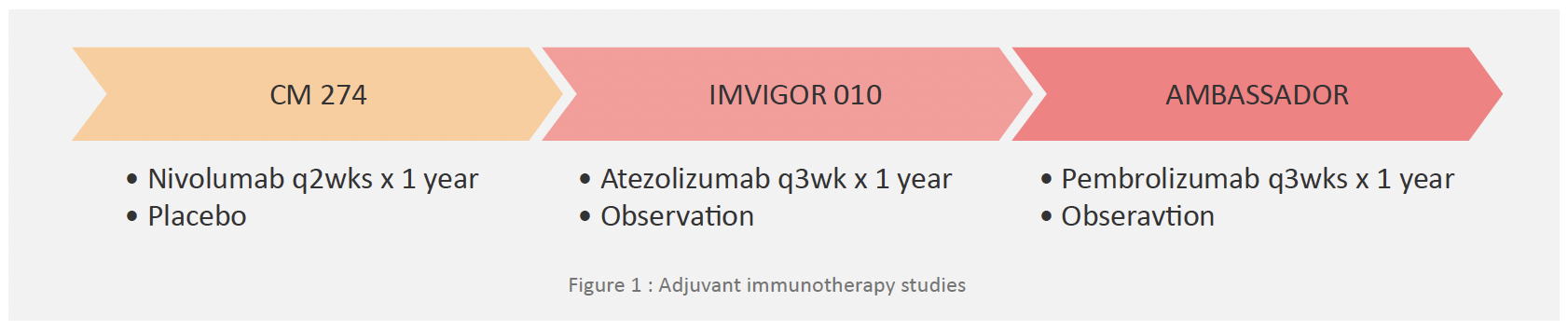

2. Adjuvant Immunotherapy

The goal of adjuvant immunotherapy is to eliminate residual cancer cells, reduce risk of relapse, and improve overall survival. Immune checkpoint inhibitors may play an important role if there is residual disease post-NAC, or in patients who did not receive NAC.

a. Nivolumab = Checkmate 274 Trial

The phase 3 CheckMate 274 trial of adjuvant nivolumab reported positive results for its primary endpoints across the entire study population, although the authors note the possibility of a larger effect size for bladder compared to UTUC. EFS was the primary endpoint and OS was the key secondary endpoint.4

DFS was 20.8 months with nivolumab compared to 10.8 months with placebo (HR, 0.70; 98.22% CI, 0.55–0.90; P < .001). For patients with a programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression level of 1% or more, DFS was 74.5% with nivolumab and 55.7% with placebo (HR, 0.55; 98.72% CI, 0.35–0.85; P < .001).

Treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or higher occurred in 17.9% of the nivolumab group and 7.2% of the placebo group. Two treatment-related deaths due to pneumonitis and one treatment-related death due to bowel perforation were noted in the nivolumab group.

Adjuvant Nivolumab should be offered as adjuvant therapy for patients with MIBC with pT3/4 and /or pN+ stage or who have residual muscle-invasive tumor (ypT2-4 or ypN+) after RC and prior cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

b. Pembrolizumab = AMBASSADOR Trial

The efficacy of adjuvant Pembrolizumab was examined by the AMBASSADOR trial as compared with observation in patients with high-risk muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma after radical surgery. The coprimary end points were DFS and OS.5

The median DFS was 29.6 months (95% CI, 20.0 to 40.7) with pembrolizumab and 14.2 months (95% CI, 11.0 to 20.2) with observation (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.90; two-sided P=0.003).

Grade 3 or higher adverse events (regardless of attribution) occurred in 50.7% of the patients in the pembrolizumab group and in 31.6% of the patients in the observation group. Among patients with high-risk muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma after radical surgery, disease-free survival was significantly longer with adjuvant pembrolizumab than with observation.

Therefore, adjuvant pembrolizumab may be considered after its approval as adjuvant therapy for patients with MIBC with pT3/4 and /or pN+ stage or who have residual muscle-invasive tumor (ypT2-4 or ypN+) after radical cystectomy and prior cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

3. Ongoing Phase II/III Trials:

a. Enfortumab vedotin = KEYNOTE-905/EV-303 Trial

This phase III trial is designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of perioperative pembrolizumab alone or in combination with enfortumab vedotin compared with RC + pelvic lymph node dissection alone in patients with MIBC who are cisplatin-ineligible or decline cisplatin-based treatment (T2-T4aN0M0 or T1-T4aN1M0).6

Dual primary endpoints are pathologic complete response as assessed by central pathologic review and EFS. Secondary endpoints include OS, DFS, pathologic downstaging rates, safety, and tolerability.

b. KEYNOTE-866 Trial

KEYNOTE-866 is a randomized phase III study to assess efficacy and safety of chemotherapy with perioperative pembro versus chemotherapy with perioperative placebo for patients with MIBC (T2-T4aN0M0) who are cisplatin-eligible.7

Primary endpoints are pathologic complete response and EFS in all patients and patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥10. Secondary endpoints are overall survival, disease-free survival, and pathologic downstaging rate stratified by CPS as well as safety.

C. Sacituzumab govitecan = SURE-02 Trial

The multi-cohort, open-label, phase II SURE study is evaluating neoadjuvant Sacituzumab govitecan + pembrolizumab followed by adjuvant pembrolizumab in patients with cT2-4N0M0 MIBC who were ineligible for or refused cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Patients receive 4 cycles of neoadjuvant Sacituzumab govitecan on days one and eight, Q3W, followed by RC.

The primary endpoint of the study is to assess the proportion of complete pathologic response (ypT0N0). Secondary endpoints include event-free survival (EFS), clinical complete response rate and OS.8

lll. IMMUNOTHERAPY IN ADVANCED BLADDER CANCER

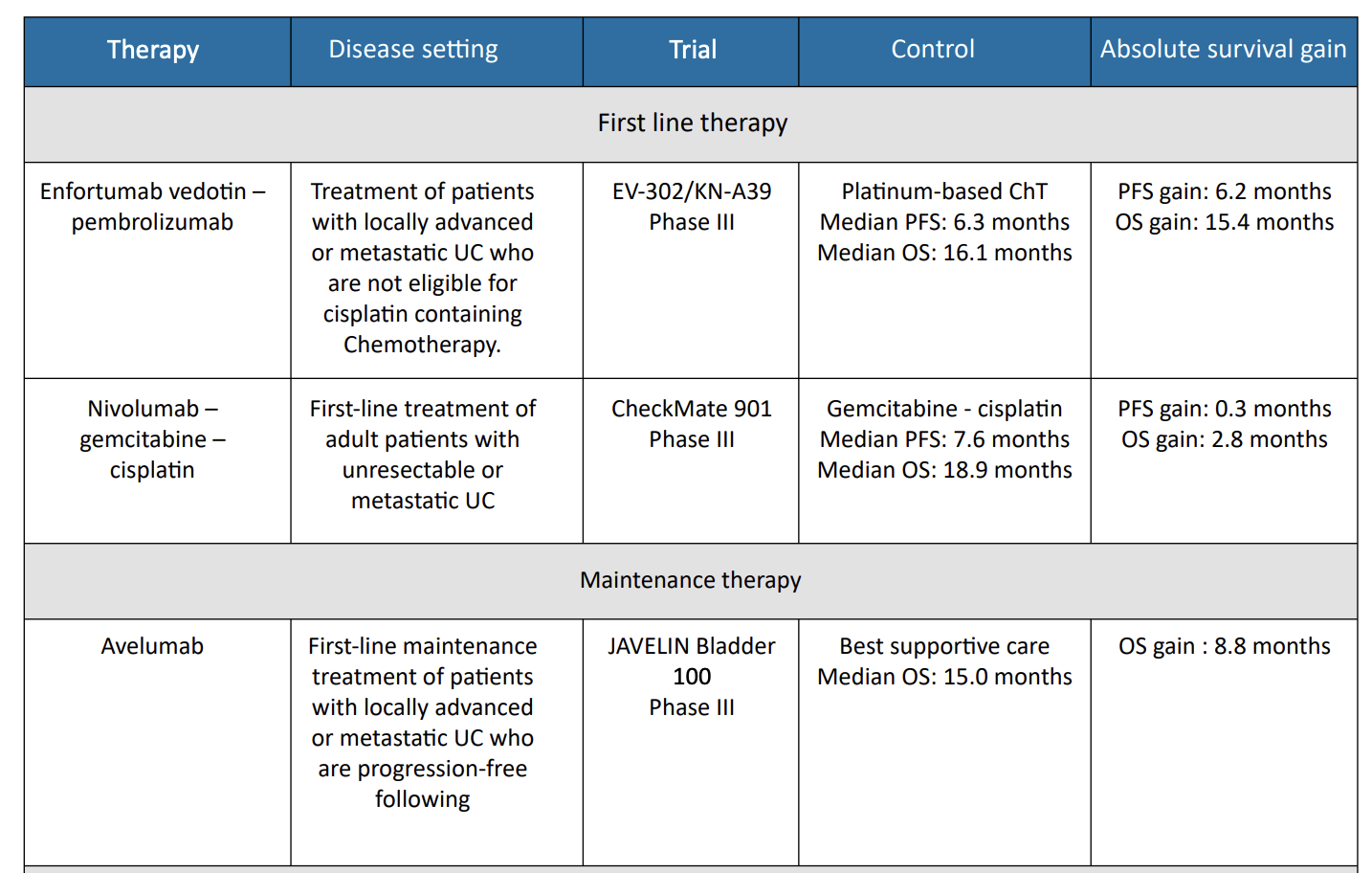

1. EV302/ Keynote – A39 Trial

Enfortumab vedotin and pembrolizumab was investigated in the phase III EV-302 trial, which randomized 886 patients

with previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma to either enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab or gemcitabine in combination with either cisplatin or carboplatin.9 The primary endpoints were PFS, as assessed by blinded independent central review, and OS.

Median PFS was significantly longer with enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab compared to chemotherapy (12.5 months vs. 6.3 months; HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.38–0.54; P < .001). Median OS was also significantly longer with enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab (31.5 months vs. 16.1 months; HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.38– 0.58; p < .001). Confirmed ORR was 67.7% and 44.4% for enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab and chemotherapy, respectively (P < .001), with complete responses observed in 29.1% of patients in the enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab group and 12.5% of those in the chemotherapy group.

Treatment-related AEs grade ≥3 occurred in 55.9% of patients receiving enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab and 69.5% of those receiving chemotherapy.

Based on these results, the combination of pembrolizumab plus enfortumab vedotin is the preferred first-line systemic therapy option for patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

2. Nivolumab = CM901 Trial

The multinational, phase III CheckMate901 study compared nivolumab plus gemcitabine-cisplatin to gemcitabine cisplatin alone in 608 patients with previously untreated unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Patients who received the nivolumab combination also received maintenance nivolumab for up to 2 years. The primary outcomes were OS and PFS. The objective response rate and safety were exploratory outcomes.10

Nivolumab plus gemcitabine-cisplatin showed longer median OS compared to gemcitabine-cisplatin alone (21.7 vs. 18.9months; HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63–0.96; P = 0.02). The median PFS was similar for the two arms (7.9 vs. 7.6 months; P =0.001), but the PFS curves separated over time. At 12 months, the PFS was 34.2% with the nivolumab combination compared to 21.8% with chemotherapy alone. The ORR was 57.6% with the nivolumab combination compared to 43.1% with chemotherapy alone. For those in the nivolumab plus gemcitabine-cisplatin group, 21.7% had complete responses.

Grade ≥3 AEs occurred in 61.8% of those in the nivolumab combination group and 51.7% of those who received chemotherapy alone. Combination therapy with nivolumab plus gemcitabine-cisplatin resulted in significantly better outcomes in patients with previously untreated advanced urothelial carcinoma than gemcitabine-cisplatin alone.

3. Avelumab = JAVELIN Bladder 100 Trial

For patients who show either response or stable disease through their full course of platinum-based first-line chemotherapy, maintenance therapy with the PD-L1 inhibitor avelumab is recommended.11

The randomized, phase III JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial showed that avelumab significantly prolonged OS in 700 randomized patients compared to best supportive care alone (median OS 21.4 vs. 14.3 months; HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.56–0.86; P = .001). The OS benefit was observed in all prespecified subgroups, including patients with PD-L1–positive tumors.

Grade ≥3 AEs were reported in 47.4% of patients treated with avelumab compared to 25.2% of those with best supportive care alone. Maintenance avelumab plus best supportive care significantly prolonged overall survival, as compared with best supportive care alone, among patients with urothelial cancer who had disease that had not progressed with first-line chemotherapy.

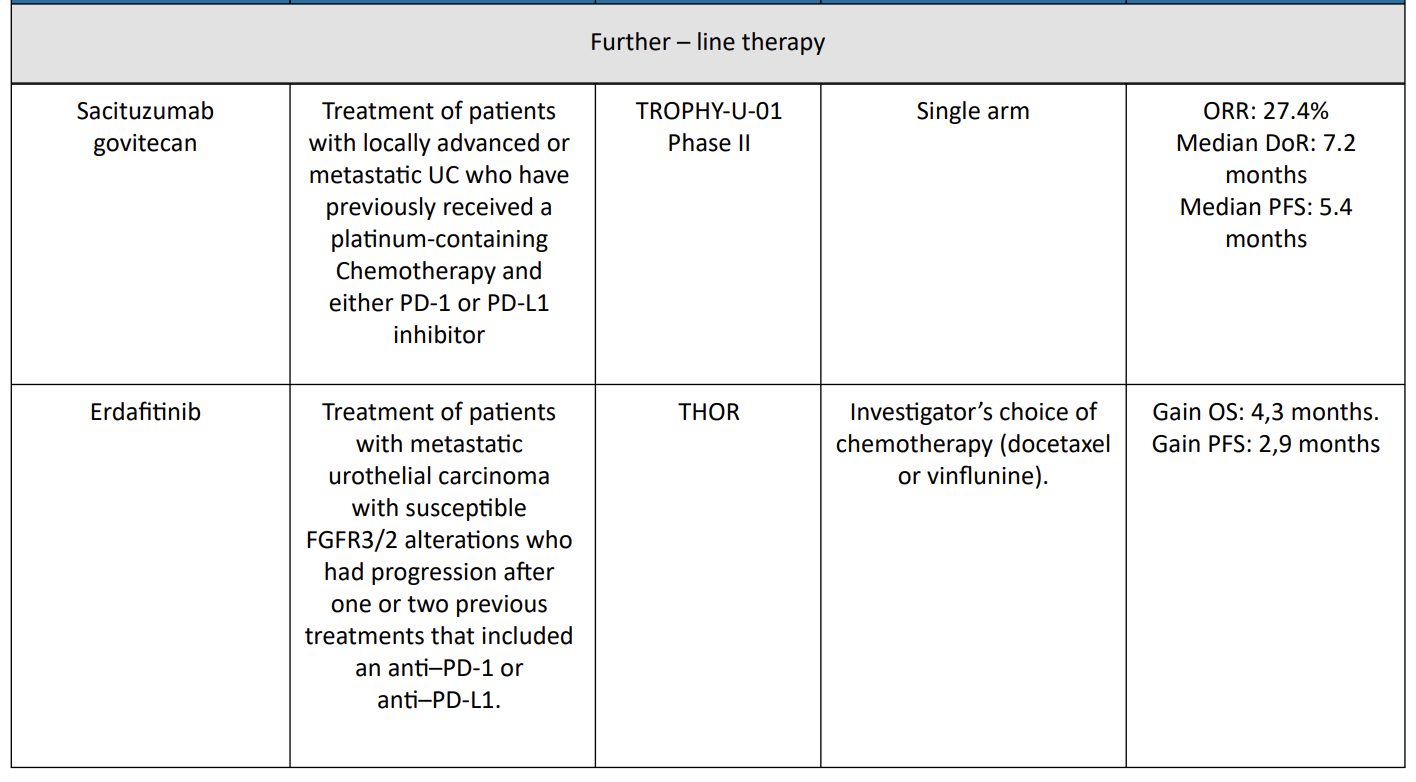

4. Sacituzumab govitecan = TROPHY-U-01 Trial

Sacituzumab govitecan has been evaluated in cohort 1 of TROPHY-U01, a phase II open-label study with 113 patients in cohort 1. Patients within this cohort had locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that had progressed following prior platinum-based and PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor therapy and were treated with sacituzumab govitecan.12

The ORR was 27% (95% CI, 19.5%–36.6%) and 77% of participants showed a decrease in measurable disease. The median DOR was 7.2 months (95% CI, 4.7–8.6 months), median PFS was 5.4 months (95% CI, 3.5– 7.2 months), and median OS was 10.9 months (95% CI, 9.0–13.8 months).

Key grade ≥3 treatment-related AEs were neutropenia (35%), leukopenia (18%), anemia (14%), diarrhea (10%), and febrile neutropenia (10%). Six percent of patients in the study discontinued treatment because of treatment-related AEs. SG monotherapy demonstrated a high ORR with rapid responses. Treatment was feasible with a manageable toxicity profile.

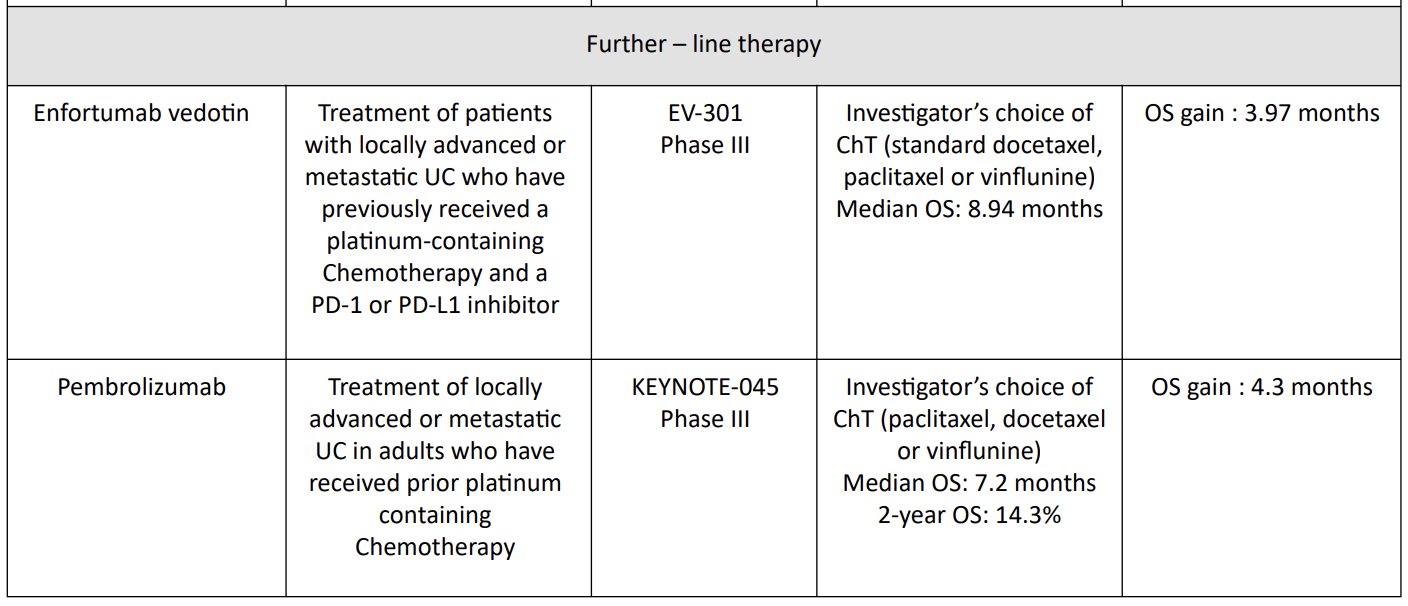

5. Pembrolizumab = KEYNOTE-045 Trial

The phase III KEYNOTE-045 study showed a superior overall survival (OS) benefit of pembrolizumab, a programmed death 1 inhibitor, versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced UC that progressed on platinum-based chemotherapy13.13 Median 1- and 2-year OS rates were higher with pembrolizumab (44.2% and 26.9%, respectively) than chemotherapy (29.8% and 14.3%, respectively). The objective response rate was also higher with pembrolizumab (21.1% versus 11.0%).

Median duration of response to pembrolizumab was not reached (range 1.6+ to 30.0+ months) versus chemotherapy (4.4 months; range 1.4+ to 29.9+ months).

Pembrolizumab had lower rates of any grade (62.0% versus 90.6%) and grade ≥3 (16.5% versus 50.2%) treatment-related adverse events than chemotherapy. Pembrolizumab continues to demonstrate superior survival over chemotherapy in patients with advanced UC after failure of platinum-based therapy, irrespective of PD-L1 status.

6. Erdafitnib = THOR Trial

THOR is a phase III trial of erdafitinib as compared with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma with susceptible FGFR3/2 alterations who had progression after one or two previous treatments that included an anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1.14

The median OS and PFS were significantly longer with erdafitinib than with chemotherapy (12.1 and 5.6 months versus 7.8 and 2.7 months, respectively). The incidence of grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events was similar in the two groups (45.9% in the erdafitinib group and 46.4% in the chemotherapy group).

Erdafitinib therapy resulted in significantly longer overall survival than chemotherapy among patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma and FGFR alterations after previous anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 treatment.

Table 1 : Therapies/indications in UC

lV. Barriers to Advanced Bladder Cancer Therapies:

Access to modern treatments for bladder cancer in Morocco, in particular immunotherapies, ADC, and targeted therapies, remains extremely limited. These new therapies, which offer increased hope of survival for patients with aggressive cancers, are inaccessible to most Moroccans for several reasons:

High cost of treatment and impact on accessibility: ADCs and immunotherapies generally cost several thousand dirhams per month. For example, pembrolizumab and atezolizumab, which are the only immunotherapy treatments currently available for bladder cancer in Morocco, remain financially inaccessible to the majority of patients without specific health insurance or substantial financial resources.15 Worldwide, the efficacy of these drugs has been shown to significantly improve survival rates of patients with advanced bladder cancer,16 but their high price makes access difficult for Moroccans. Other bladder cancer drugs used elsewhere, such as nivolumab or antibody-drug conjugates (such as enfortumab vedotin), are not available in Morocco.

Health insurance issues: Social insurance in Morocco, although expanding with programs such as RAMED and AMO, often does not cover expensive oncology treatments, particularly those of the latest generation.17 Immunotherapies and ADCs for bladder cancer are not included in the standard reimbursement lists, and patients often must pay the full cost of treatment themselves. This severely limits treatment options for middle-class and low-income patients, who simply cannot afford such treatments without additional financial support.18 Private insurers, although sometimes offering broader cover options, do not systematically include immunotherapies and ADCs in their contracts, leaving the majority of patients with limited choices.19

Access to new bladder cancer therapies is strikingly uneven worldwide. In high-income countries, these therapeutic advances now represent an increasingly standard treatment option for advanced or metastatic bladder cancer, with promising results in terms of OS and PFS. However, in low- and middle-income countries, access to these innovations remains limited or non-existent due to a number of factors, including prohibitive cost, lack of adequate reimbursement systems and lack of specialized infrastructure.20

Scientific advances in oncology should benefit all patients, regardless of their country of origin or financial resources. Unequal access to cuttng-edge therapies for bladder cancer represents a major ethical and public health challenge. Indeed, the World Health Organisation (WHO) emphasises the need for equity in healthcare and recommends concerted efforts to facilitate access to essenttal medicines and new therapies in low- and middle-income countries.21 International funding initiatives, partnerships between governments and the pharmaceutical industry, and differential pricing policies could help to reduce this inequality.22 In addition, the development of clinical research networks in countries with limited resources could facilitate the introduction of innovative therapies by providing access to clinical trials.23

Written by:

Karima Oualla, MD, MSc, Mehdi Alem, MD, and Nawfel Mellas, MD

- Medical Oncology Department, Hassan II University Hospital Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fes, Morocco

- Hamid ARAH, Ridwan FR, Parikesit D, Widia F, Mochtar CA, Umbas R. Meta-analysis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared to radical cystectomy alone in improving overall survival of muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients. BMC Urology. 14 oct 2020; 20:158.

- Powles T, Catto JWF, Galsky MD, Al-Ahmadie H, Meeks JJ, Nishiyama H, et al. Perioperative Durvalumab with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Operable Bladder Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 0(0).

- Basile G, Bandini M, Gibb EA, Ross JS, Raggi D, Marandino L, et al. Neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab and Radical Cystectomy in Patients with Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Bladder Cancer: 3-Year Median Follow-Up Update of PURE-01 Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 1 déc 2022;28(23):5107-14.

- Bajorin DF, Witjes JA, Gschwend JE, Schenker M, Valderrama BP, Tomita Y, et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Placebo in Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2 juin 2021;384(22):2102-14

- Apolo AB, Ballman KV, Sonpavde G, Berg S, Kim WY, Parikh R, et al. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab versus Observation in Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 0(0)

- Necchi A, Bedke J, Galsky MD, Shore ND, Plimack ER, Xylinas E, et al. Phase 3 KEYNOTE-905/EV-303: Perioperative pembrolizumab (pembro) or pembro + enfortumab vedotin (EV) for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). JCO. 20 févr 2023;41(6_suppl): TPS585-TPS585.

- Siefker-Radtke AO, Steinberg G, Bedke J, Nishiyama H, Martin J, Kataria R, et al. KEYNOTE-866: Phase III study of perioperative pembrolizumab (pembro) or placebo (pbo) in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cisplatin (cis)-eligible patients (pts) with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Annals of Oncology. 1 oct 2019;30: v401.

- Cigliola A, Moschini M, Tateo V, Mercinelli C, Patanè D, Crupi E, et al. Perioperative sacituzumab govitecan (SG) alone or in combination with pembrolizumab (Pembro) for patients with muscle-invasive urothelial bladder cancer (MIBC): SURE-01/02 interim results. JCO. 10 juin 2024;42(17_suppl): LBA4517-LBA4517.

- Powles TB, Valderrama BP, Gupta S, Bedke J, Kikuchi E, Hoffman-Censits J, et al. LBA6 EV-302/KEYNOTE-A39: Open-label, randomized phase III study of enfortumab vedotin in combination with pembrolizumab (EV+P) vs chemotherapy (Chemo) in previously untreated locally advanced metastatic urothelial carcinoma (la/mUC). Annals of Oncology. 1 oct 2023;34: S1340.

- van der Heijden MS, Sonpavde G, Powles T, Necchi A, Burotto M, Schenker M, et al. Nivolumab plus Gemcitabine-Cisplatin in Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 9 nov 2023;389(19):1778-89.

- Powles T, Park SH, Voog E, Caserta C, Valderrama BP, Gurney H, et al. Avelumab Maintenance Therapy for Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 23 sept 2020;383(13):1218-30.

- Loriot Y, Petrylak DP, Rezazadeh Kalebasty A, Fléchon A, Jain RK, Gupta S, et al. TROPHY-U-01, a phase II open-label study of sacituzumab govitecan in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma progressing after platinum-based chemotherapy and checkpoint inhibitors: updated safety and efficacy outcomes. Ann Oncol. avr 2024;35(4):392-401.

- Fradet Y, Bellmunt J, Vaughn DJ, Lee JL, Fong L, Vogelzang NJ, et al. Randomized phase III KEYNOTE-045 trial of pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel, docetaxel, or vinflunine in recurrent advanced urothelial cancer: results of >2 years of follow-up. Ann Oncol. 1 juin 2019;30(6):970-6.

- Loriot Y, Matsubara N, Park SH, Huddart RA, Burgess EF, Houede N, et al. Erdafitinib or Chemotherapy in Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 22 nov 2023;389(21):1961-71.

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Programme of Action for Cancer Therapy (PACT) IAEA, 2019.

- National Cancer Institute (NCI). Bladder Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version. U.S. National Institutes of Health, 2021.

- Fondation Lalla Salma Les prises en charge, disponible sur : https://www.contrelecancer.ma/fr/les_prises_en_charge.

- Amal Yassine et al. Les caractéristiques de la population couverte par le régime de l’assurance maladie obligatoire au Maroc. Pan African Medical Journal. 2018 ;30 :266.

- Ferrié J.N. L’accès aux soins des personnes atteintes d’un cancer et les limites du RAMed., disponible sur : http://www.abhatoo.net.ma/maalama-textuelle/developpement-economique-etsocial/developpement-social/sante/couverture-medicale/l-acces-aux-soins-des-personnesatteintes-d-un-cancer-et-les-limites-du-ramed.

- The Lancet Oncology. Global Disparities in Cancer Outcomes.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Expenditure Database.

- WHO Technical Report Series. Pricing of Cancer Medicines and their Impacts. Geneva : WHO, 2018.

- Rapport du Conseil économique, social et environnemental. SOINS DE SANTÉ DE BASE : VERS UN ACCÈSÉQUITABLE ET GÉNÉRALISÉ.